- Open today, noon to 5 pm.

- Parking & Directions

- Free Admission

Pigments and Polish: Varnish and Retouching

Once damaged, a painting can never truly be fixed. Unlike our own scars, those of a painting will never fade. However, with the help of a conservator, the damage can be skillfully and sometimes totally concealed. More often, the goal is to push back the appearance of the damage just enough to allow the viewer’s eye to wander over it. The technical term for this is retouching: the application of new color where it has been lost. In the past, restorers and artists used all manner of painting materials to achieve this, though oil paint was typically a popular choice to retouch oil paintings. Unfortunately, within a decade, retouchings done with oil paint tend to discolor as the oil medium undergoes natural chemical changes. What was once a perfect match can become glaringly obvious and more distracting than the damage it was originally attempting to conceal. Past restoration of Glintenkamp’s A Mexican Symphony showcases this discoloration. In an area of damage to the bottom of the painting, old retouches in oil paint appear as grey-brown.

This is Part Three, of a three-part series. Read Part One and Part Two.

Discolored overpaint from past treatment. The cool blue water abruptly becomes a grey-brown. The surrounding areas are also overpainted with muddled looking oil paint.

Old Problems, New Solutions: Modern Materials for Retouching

The discoloration of these repairs combined with the yellowing of natural varnishes often lead to the frequent cleaning of paintings with solvents. Before the advent of modern chemistry, a limited range of options often meant that harsh and caustic solutions were employed to clean painted works, resulting in chemically damaged surfaces. After cleaning, the painting would then be revarnished and retouched with more oil paint, eventually needing the same potentially dangerous cleaning. In the twentieth century, conservators realized the need to rescue paintings from this cycle and began exploiting the modern materials of the era. Pigments ground in synthetic resins (and not oil) offered a momentous change. These resins were engineered to stay clear and readily soluble in solvents that were not likely to harm dried oil paint. The invention of new, light-fast pigments also superseded the traditionally costly and fugitive (liable to fading) ones like alizarin crimson and Indian yellow. These new resin paints thus had the potential to remain true and unchanged for several decades, if not longer.

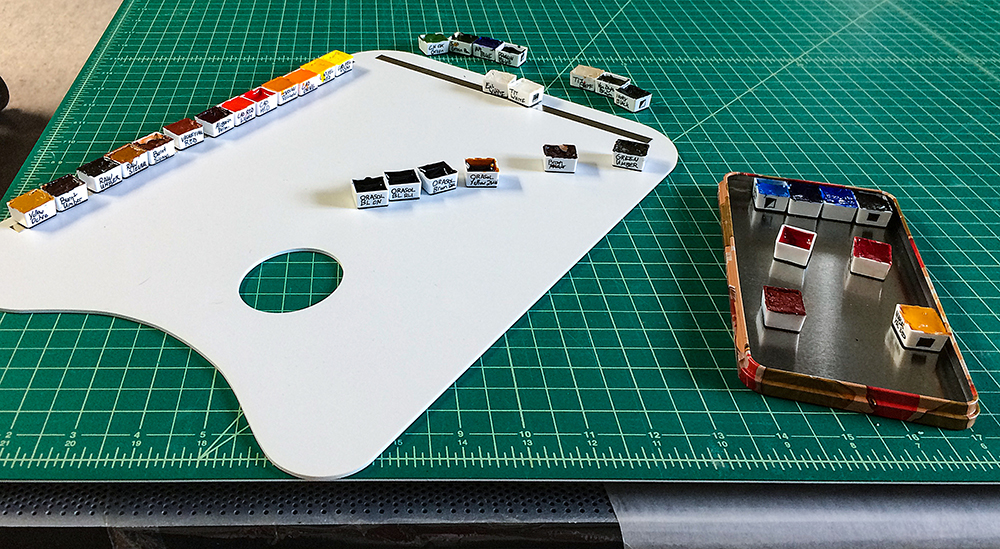

A typical retouching palette for the contemporary conservator.

To conceal the new repairs to the canvas of Glintenkamp’s A Mexican Symphony, a particularly modern material was used. Aquasol® is novel polymer that is readily soluble in water and alcohols. When mixed with pigments, it can be applied like watercolor. With the addition of more binder, it can also helpfully take on the gloss and saturation of oil paint. Gamblin QoR® colors offer a convenient commercial option for conservators and artists alike. These colors should stay true. If they do discolor, they should remain easily removable for decades to come. A very fine brush is used to dot this retouching color where the original paint has been lost. Colors must be perfectly matched, and application must be precise. Often, conservators work with magnifying lenses to ensure that the retouching is not applied over any of the original paint layer. As with A Mexican Symphony, carefully retouching areas of damage can near seamlessly reintegrate these distractions back into the composition, allowing the work to read as whole again.

Aquasol based QoR colors used for retouching

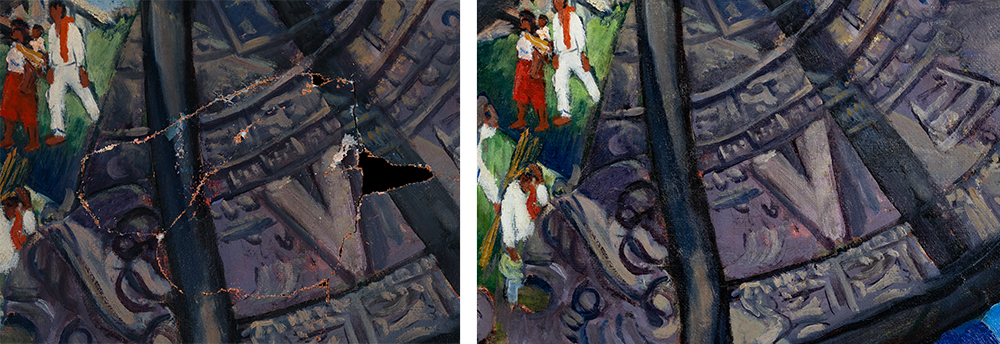

An area of overpaint after cleaning, retouching and varnishing. Despite revealing significant damage under the old overpaint, after retouching the area once again has clarity, and reads consistently with the rest of the painting.

Detail of the tear before and after repair and retouching.

Glossing Over the Details: The Varnishing of Paintings

The final stage of this conservation treatment was varnishing. Before the advent of Modernism in the twentieth century, most paintings were varnished with products composed of tree resins ranging from tropical dammar to precious amber, the semi-fossilized resin of ancient trees. Varnish in the nineteenth century became particularly integral to the painting process. Layers of thin varnish were frequently applied between painting sessions to saturate the work in progress and give painters a better impression of what their finished work would look like. Varnish is so critical to the finishing of an oil paintings because it preserves colors with the chroma and saturation with which they were first painted. As a painting dries, thinly painted portions may become disproportionately matte. As the painting ages, the whole of the surface will eventually become more matte and appear clouded. Varnish additionally protects the surface, acting as a sacrificial layer that absorbs damaging ultraviolet light and blocks airborne soiling.

In the last blog post I explored the process of removing layers of soiling and varnish from the surface of the work (hyper link Mastic and Mire: The Cleaning of Paintings). Natural varnishes are often cleaned away every half- or quarter-century as they accumulate significant discoloration. The original paint surface revealed will almost always appear clouded and hazy afterwards—like the surface has been covered in frosted glass. In order to bring the color and saturation back, nearly all works cleaned of varnish will necessitate revarnishing. Deciding the final finish of a painting is critical to the appearance of the work. Conservators may research extensively the intended surface effects of the artist or the broader trends of the period in which the painting was made. Furthermore, the conservator must consider the other factors of applying a new material to the surface of a painting. A new varnish must not contain solvents that will harm the paint, and the varnish should ideally remain soluble in the same solvents for many decades. Conservators now have a broad range of choices when it comes to varnish. Some still opt for traditional tree resins like mastic and dammar, while others utilize modern synthetic varnishes that are engineered to stay clear and colorless for up to 100 years.

An example of typical desaturation with varnish removal (old retouches have also been removed). Check out Restoring the Portrait of Francesco Bollani for more on this project.

Modern and Matte: Varnishing A Mexican Symphony

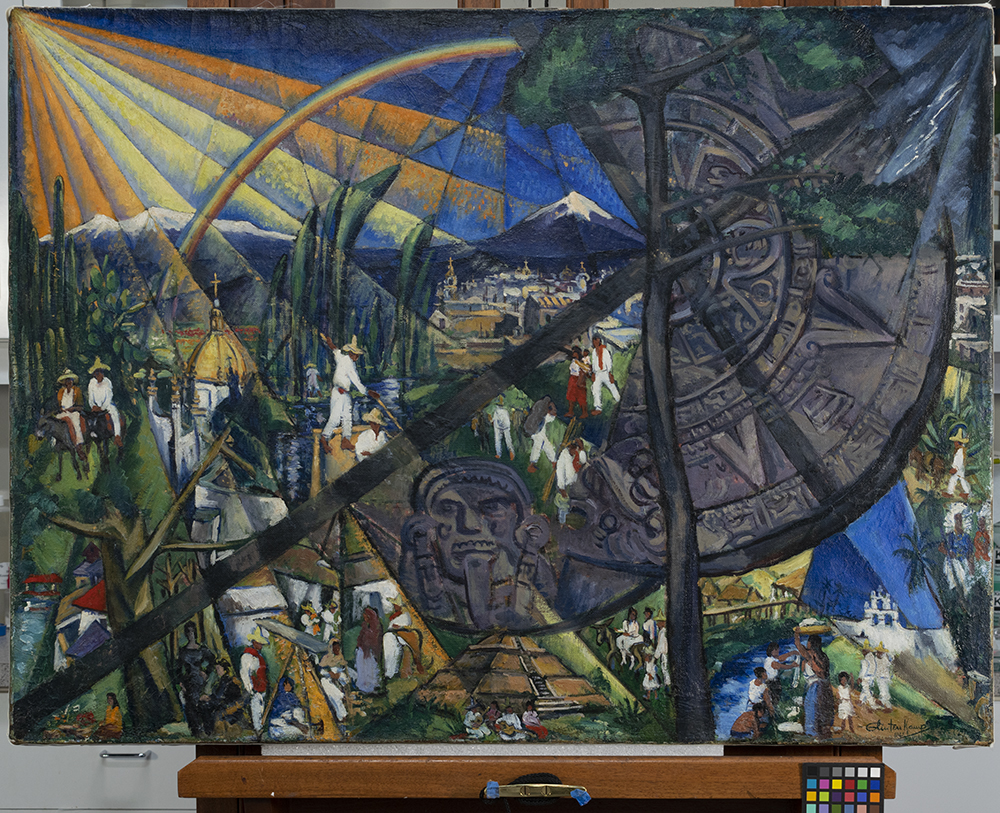

A Modernist work like Glintenkamp’s A Mexican Symphony requires a critical evaluation of influences and intent. The influence of Futurism and Cubism are apparent in the dynamic and graphic quality of the work, with diagonal planes of composition breaking up the surface. Cubist painters like Picasso often insisted their works never be varnished because they exploited subtle surface effects of matte against glossy oil paint. A rich, fully applied coat of varnish, like that of an Old Master work like Ruben’s Portrait of the Archduchess Isabella Clara Eugenia, would be inappropriate and even anachronistic for the surface of A Mexican Symphony.

Pablo Picasso (Spanish, 1881–1973), Composition for Bal de la Mer, 1928, Oil on canvas, Gift of Walter P. Chrysler, © Estate of Pablo Picasso / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York, 71.689

Attributed to Peter Paul Rubens (Flemish, 1577-1640), The Archduchess Isabella Clara Eugenia, ca. 1616, Oil on canvas. Gift of Walter P. Chrysler, Jr. 71.462

Because A Mexican Symphony was previously varnished, the work appeared hazy after it was cleaned. Colors like the deep blue appeared disparately clouded. A careful application of varnish was necessary to resaturate the work without giving it the substantial finish of a more traditional oil work. A thin varnish of Regalrez-1094, the main component of many commercial varnishes like Gamvar®, provided an ideal base. By adding a small amount of wax to the varnish and brushing the varnish continuously until dry, the surface was given an appearance closer to fresh oil paint than a fully varnished surface.

Final, after varnishing and retouching.

With a few more minor retouches, the painting is now ready for display. From a short distance, the brilliant hues of Glintenkamp’s dynamic composition have once more become the main focus. Look close though and you might be able to make out the faint scars of its past life. This is the balance that modern conservation often aims to find— privileging the work of the artist while retaining the evidence of the object’s life.

Conclusion: Prognosis of a Painting

When A Mexican Symphony was first acquired, the work was at risk of being lost to damage and deterioration. With the help of conservation, the painting has now been stabilized and restored to its former colorful appearance. Despite these repairs, however, the work remains a layer of aged paint on a fragile canvas. Its preservation into the future depends on its careful treatment. At the Chrysler Museum, the work finds a comfortable and safe home to ensure its long-term care, preserving our cultural heritage for visitors like you for decades to come.