- Open today, noon to 5 pm.

- Parking & Directions

- Free Admission

Mastic and Mire: The Cleaning of Paintings

–Brandon Finney, 2019–2020 NEH Conservation Fellow

Henry Glintenkamp’s Symphony No 1 in Gold and Green (A Mexican Symphony), on view in Journeys Across the Border: U.S. & Mexico, came to the Chrysler Museum in 2019 in a fragile state. The painting, a gift from the artist’s granddaughter, required extensive repair and cleaning before going on view. In the past, all manner of methods were attempted to clean paintings. A cut potato or onion was used to remove grime. Spoiled wine and caustic ammonia dissolved aged and discolored varnish. Contemporary conservators continue to use some ancient methods. You might be surprised to learn that saliva is an excellent cleaning agent for general surface grime. While discussions of patina continue to be an important consideration in the conservation of paintings, it is generally agreed that works should not be mired in surface soiling that may considerably hide the true appearance of a work. (This is part two of a three-part series. Read part one, Glue and Gauze, first.)

Contemporary Cleaning Methods: Chemistry in Action

Instead of potatoes or onions, conservators now have a suite of acids, bases, chelators, and surfactants available to make custom water-based cleaning solutions. Carefully rolled onto the surface with cotton swabs or dabbed with a soft cosmetics sponge, the goal of using these solutions is to remove soiling from the picture’s surface without affecting the paint layers below.

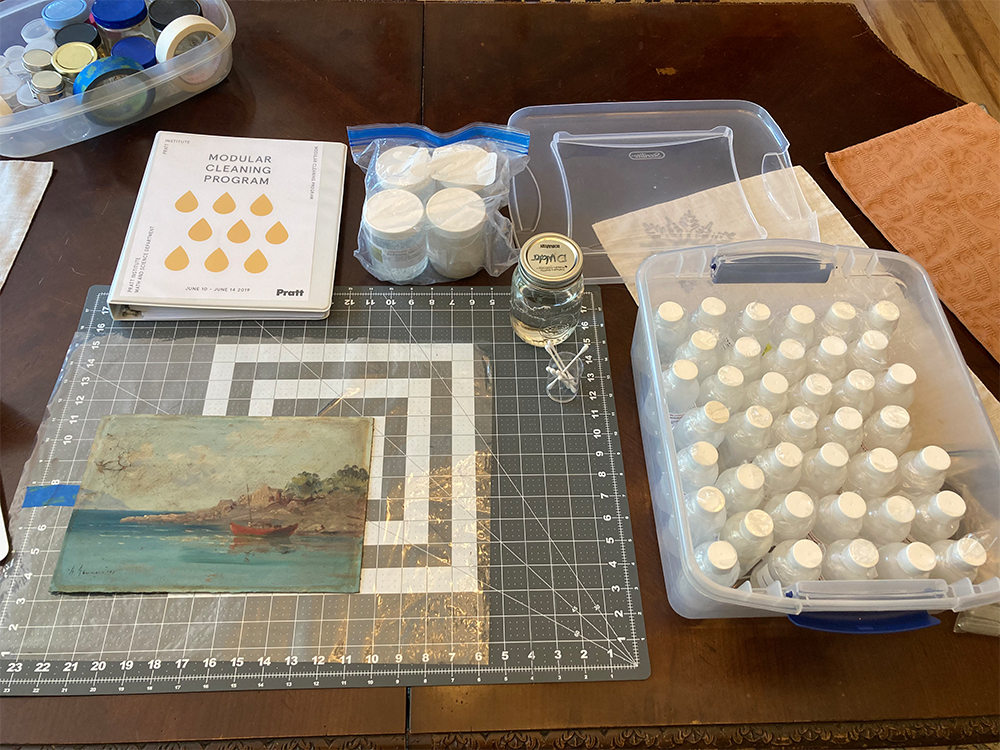

A set of cleaning solutions set out for testing. Seascape, Anonymous, Greek, Early 20th century, Oil on board, Private Collection, Canada

Acids and bases can be used to set the pH of the solution. Working at an acidic pH can prevent the lifting of sensitive paint, while working at higher alkaline pH can help remove grime. Chelators, like citric acid, are molecules that bind with metal ions. Chelators can further aid in the uptake of soiling but may also bite into paint layers containing metal-based pigments like cadmium reds. Surfactants are soapy compounds that help bring oily grime into the water-based cleaning solution. Like any soap in our homes, they can be very effective at cleaning; but they may be so effective as to also negatively act on the oils in an oil paint layer, resulting in the loss of pigments and paint. The careful selection and testing of these varying elements allows a conservator to find a balance between removing the soiling on a painting and affecting the paint layers below. Spot testing is critical to ensure the solution is both effective and safe before cleaning the whole work. The careful attenuation of these modern solutions has allowed for the cleaning of very sensitive artworks that otherwise would have gone uncleaned in the past or been considerably damaged in the process.

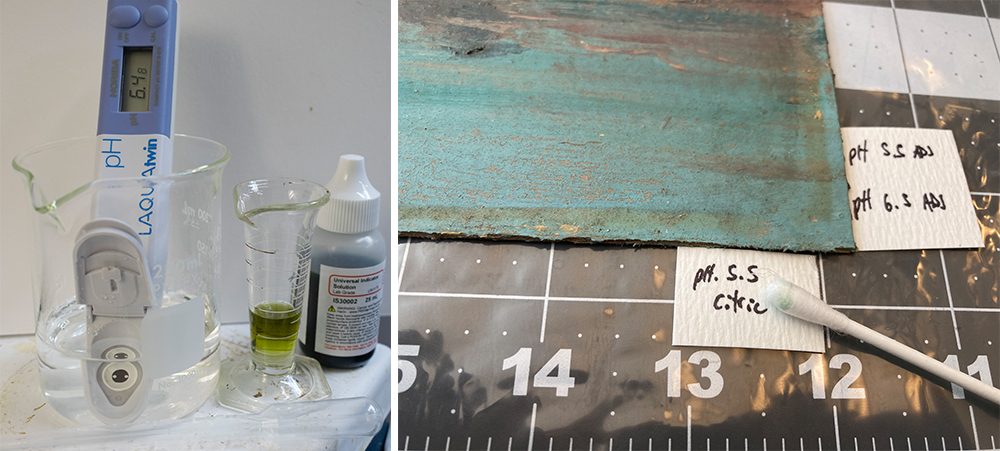

(left) A pH meter and a liquid pH indicator used to set the pH of cleaning solutions. (right) Testing a painting for cleaning – an example of a cleaning solution that also lifts pigments/paint.

Grayed Out: Cleaning A Mexican Symphony

It may seem like a lot of fussy chemistry to simply clean the surface of a painting, but paintings are often surprisingly dirty objects. In the case of A Mexican Symphony, the painting was markedly discolored with considerable surface grime. The whites of the painting clearly showed this; what were intended as bright, cool whites were concealed by gray. A painting like this can require dozens of swabs to remove the heavy layer of soiling. In this case, a solution of citric acid and surfactant was found to safely and effectively clean the work.

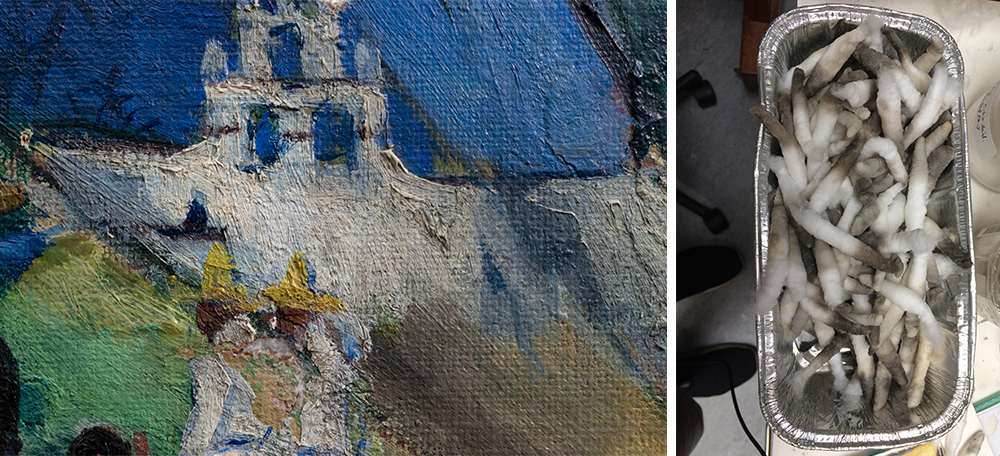

(left) Detail of cleaning test showing the true color of the white passages of paint. (right) Swabs used to clean the work.

Cleaning revealed a much more vibrant and saturated color palette, but the original surface of the painting was still being obscured by a layer of considerably discolored varnish. For a modern work of art, the aged appearance was out of step with the brilliant colors hiding underneath. The next step in its conservation was the removal of this aged varnish layer.

Before surface cleaning

After surface cleaning

Cold Cream: Cosmetics Chemistry for the Cleaning of Paintings

Twentieth century paintings like this one are still relatively “young.” The solvents that can remove varnish layers may also damage the paint layers, so solutions must be carefully tested. As in the case of water-based cleaning, methods for employing solvents have considerably improved. Spoiled wine has been replaced by highly refined lab-grade solvents and an accompanying knowledge of their chemistry. Particularly useful are the novel solutions borrowed from the cosmetics and personal care product industry. In the case of removing the varnish from A Mexican Symphony, the paint layers were sensitive to the solvents that could dissolve the varnish, which itself was difficult to dissolve. The solution found was to attenuate the action of the solvents by gelling them in a matrix of Carbopol®, an acrylic compound that gives the gel texture to hand sanitizers and cleansers. The gel matrix keeps the solvent at the surface of the painting, interacting primarily with the varnish layer and not the paint layers below. This keeps the paint layers safe while allowing the solvent enough time on the surface to dissolve the stubborn varnish. The gel was applied by brush, gently moved across the surface, and allowed to remain for a few moments. Cotton swabs were then used to remove the gel before the surface was rinsed with another solvent to remove any residual gel and varnish. The results are quite evident in the image below showing the discoloration of the gel removed from the surface.

(left) Gel on the surface of the painting. (right) Discolored gel removed from the surface.

During varnish removal. To the left of the diagonal line has been cleaned. The right remains much darker and grey.

For especially sensitive spots, like areas of the dark blue sky, another solution from cosmetics chemistry was employed. These areas could not hold up to the solvent gel, so instead they were brushed with a protective solvent called D5 (decamethylcyclopentasiloxane). D5 is found in nearly all moisturizers today as the solvent for dimethicone polymers that seal in water to the skin or give products a satisfying slippery feeling. Rather than sealing moisture into the skin, D5 functions as a barrier layer for a painting that allows for strong solvents like acetone (often the active component of nail polish remover) to be rolled onto the surface with great control. Because acetone and D5 cannot mix, the acetone only reaches the uppermost discolored varnish when gently rolled across the surface. Once the varnish has been removed, the D5 slowly evaporates from the paint surface in the same way moisturizer dries on your skin. In this case though, no residues are left behind on the freshly cleaned paint layer.

(left) Before cleaning, (right) after cleaning.

The painting has now come an incredibly long way since it entered the conservation lab. The colors concealed by grime and varnish have now been revealed along with fine details in Glintenkamp’s design and paint strokes. Without varnish, the painting still appears slightly hazy and desaturated in color. In the final installment of this series, I’ll show you how paintings are varnished and damages retouched.