- Open today, 10 am to 5 pm.

- Parking & Directions

- Free Admission

Object of the Week: Emma Stebbins’ Samuel

Emma Stebbins (American, 1815–1882), Samuel, modeled ca. 1865–66, carved 1870, Marble, Gift of James H. Ricau and Museum purchase, 86.521

Like a child who has unwittingly wandered into his parent’s Zoom meeting, Emma Stebbins’s Samuel captures the tender awkwardness of a youth who seems out of place. The diminutive figure is that of the prophet Samuel, whose story is told in the Hebrew Bible. According to scriptures, Samuel was a young boy working in the shrine at Shiloh when he heard a voice calling his name one evening. Understandably confused, he told the high priest Eli what he heard. After rebuffing Samuel’s disruptions several times and sending him back to bed, Eli realized that the Lord was speaking to Samuel. He instructed the boy to answer if called again to show that he was ready to hear God’s word. The message young Samuel received was an uncomfortable one: the Lord told him that Eli’s sons’ evil deeds had condemned the family’s dynasty. Nevertheless, Samuel passed the message on in full and thereby cemented his status as a prophet of God.

Stebbins created Samuel while living in Rome, where she enjoyed a relatively brief but prodigious career as a sculptor working in marble. She was born in New York, where she developed her talents as a painter before departing for Rome at the age of forty to dedicate herself wholeheartedly to the life of a sculptor. Rome was the epicenter of the neoclassical movement in sculpture. The city provided Stebbins abundant opportunities to interact with leading artists, study examples of classical antiquity, and engage skilled craftsmen who possessed the highest level of technical expertise in the realm of modeling and carving. Living as an expatriate also afforded Stebbins and other American women greater freedom from social and professional bounds that governed their lives in the United States. In Rome, Stebbins joined a vibrant community of women sculptors whose ranks included Harriet Hosmer, Margaret Foley, and Edmonia Lewis. The renowned actress Charlotte Cushman was also among them and served as the group’s unofficial organizer and champion. For Stebbins and Cushman, the bond was even closer as the two nurtured a deep and loving union that would continue their whole lives. Cushman described their relationship in terms of marriage, writing to a friend, “Do you know that I am already married and wear the badge upon the finger of my left hand?”[i]

Photographer Unknown, Charlotte Cushman and Emma Stebbins, Theatrical Cabinet Photographs of Women (TCS 2). Harvard Theatre Collection, Houghton Library, Harvard University.

Cushman worked tirelessly to promote the work of the naturally shy and retiring Stebbins and the artist’s career flourished. For a little over a decade, Stebbins produced a wide array of works in marble, enjoyed warm reception for her art at esteemed gallery shows, and won important public commissions. Stebbins ranged widely in her subjects, which included portraiture, figures from history and the Bible, and allegorical subjects. Though meant to illustrate a Biblical story, the Chrysler’s Samuel blends genres as the model for the figure was Stebbins’s nephew, John Neal Tilton.

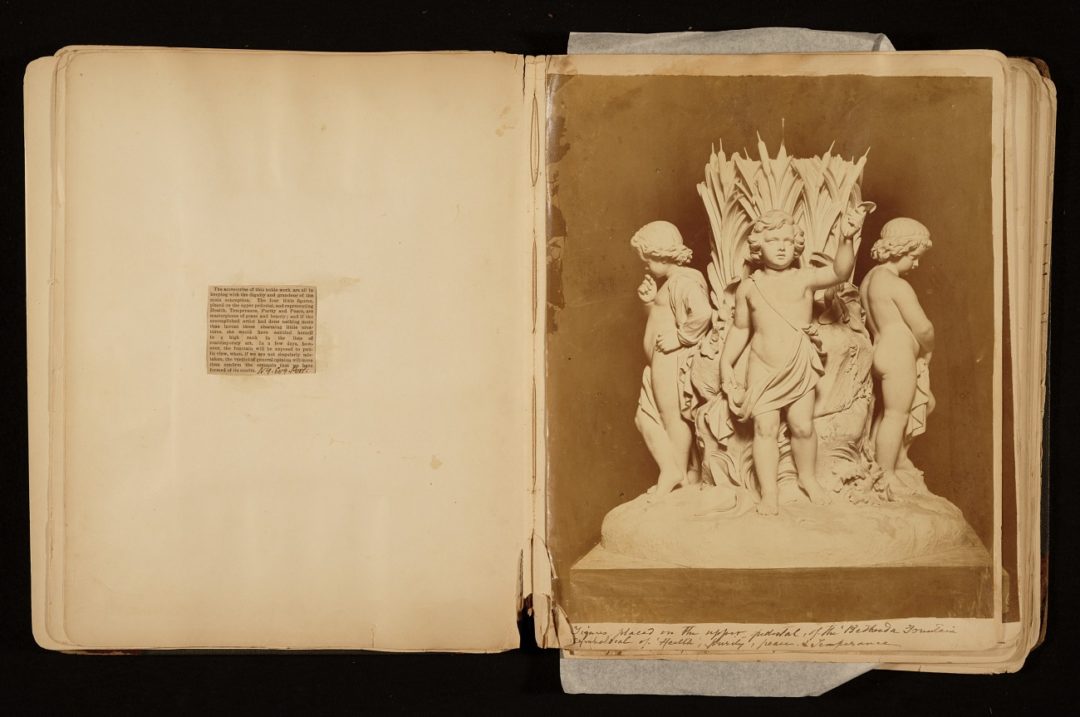

Photographer Unknown, Model of Pedestal Figures for the Bethesda Fountain, by Emma Stebbins. Emma Stebbins scrapbook, 1858-1882. Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution

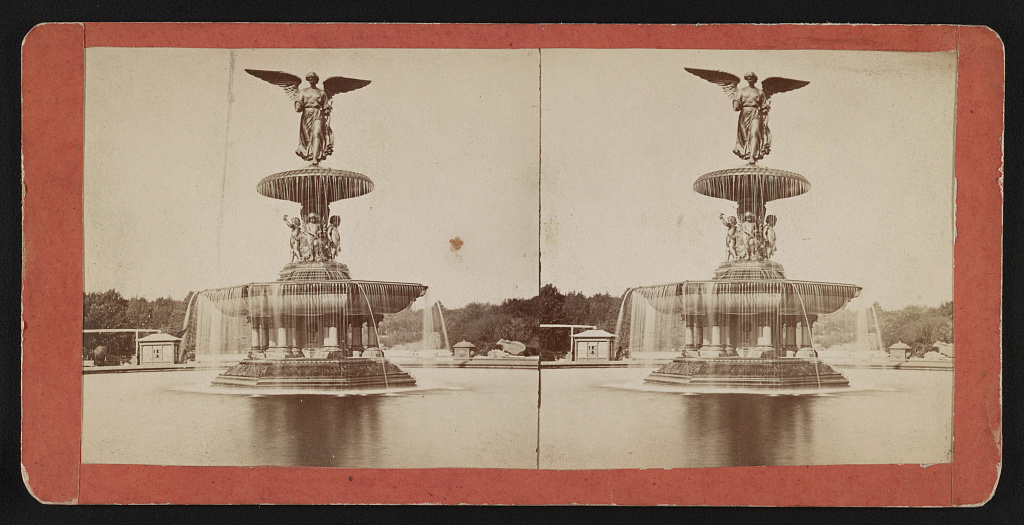

Photographer Unknown, Stereocard of Bethesda Fountain, Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division

The boy also served as a model for the pedestal figures, which formed part of Stebbins’s most important and high profile commission, the Bethesda Fountain situated in New York’s Central Park. Created to commemorate New York’s first fresh water system, the fountain is topped by an eight-foot-tall bronze sculpture known as the Angel of the Waters—who, according to the Bible, blessed the waters at the pool at Bethesda with healing properties. Stebbins received the commission for the fountain in 1862, the first public art commission awarded to a woman in New York City, but the work was not unveiled until 1873. Critics had mixed reactions to Stebbins’s work at the time, but the fountain has since become one of the city’s iconic sites, appearing as a backdrop in countless films and tv shows. Perhaps most notably, the fountain served as the setting for the final scene in Tony Kushner’s Pulitzer Prize-winning play Angels in America, which explored themes of homosexuality, homophobia, and the AIDS crisis in Reagan-era America.

In 1870, Stebbins left Rome to care for Cushman, whose health was steadily declining as she suffered from breast cancer. The two settled back in the United States, where they continued to live together until Cushman’s death in 1876. Stebbins devoted herself to writing a biography of her partner and retired from her public career as a sculptor. Today, only a handful of Stebbins’s works survive in public collections, offering only scattered signposts of a brilliant career. One of her final works, carved around the same time as the Chrysler’s Samuel, was a bust of Cushman, now held by the Charlotte Cushman Foundation in Philadelphia.

–Corey Piper, PhD, Brock Curator of American Art

[i] Quoted in Elizabeth Milroy, “The Public Career of Emma Stebbins: Work in Marble,” Archives of American Art Journal 33 (1993), 4.