- Open today, noon to 5 pm.

- Parking & Directions

- Free Admission

Glue and Gauze: Surgical Repair of Canvases

Introduction: A New Acquisition

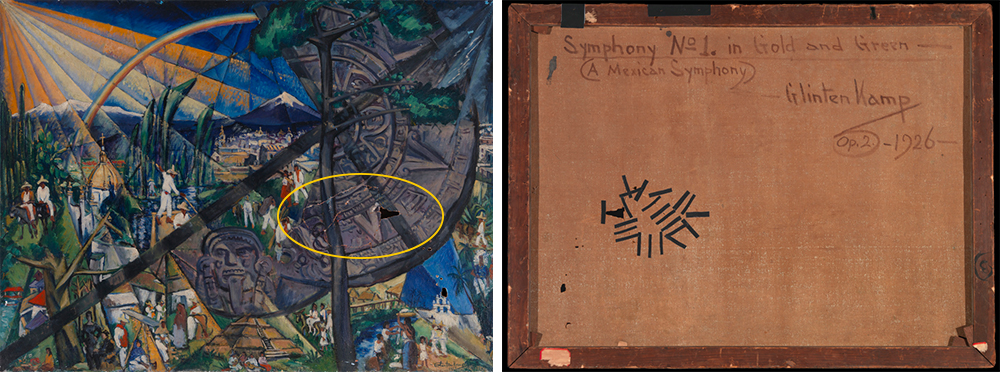

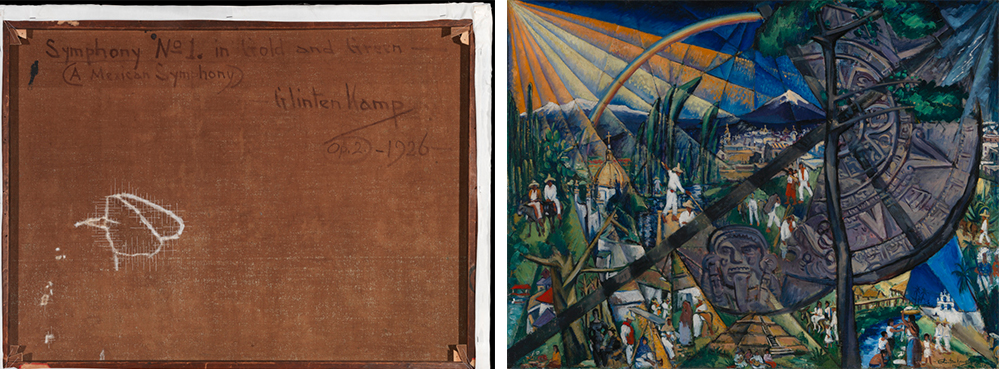

In 2019, the Chrysler acquired Symphony No 1 in Gold and Green (A Mexican Symphony) (1925/26) by the celebrated American painter Henry Glintenkamp. The painting came from the collection of his granddaughter Pamela Glintenkamp, who describes the work as an eclectic mix of European Futurism and Cubism combined with the influences of Mexican muralists Diego Rivera and David Alfaro Siqueiros. Visitors can get their first glimpse of the work in Journeys Across the Border: U.S. & Mexico, on view in the Chrysler’s modern galleries. The new installation displays how the border between the neighboring countries has been a gateway for the flowing of ideas and learning for more than a century. Glintenkamp’s painting appears alongside works by Rivera, José Clemente Orozco, Elizabeth Catlett, Paul Strand, Miguel Covarrubias, and Pablo (Paul) O’Higgins. This vibrant work features an idyllic image of contemporary Mexican culture, a dynamic blend of pre-colonial tradition in harmony with the Catholic beliefs that would come to typify the religious practices of Mexico.

Despite the excellent quality of the painting, A Mexican Symphony came to the Chrysler Museum in a very fragile state. Considerable damage to the canvas and wooden stretcher placed the work at risk of being lost. A large section of the canvas had split away from the stretcher and a patch of canvas had been completely torn out of the work. Additionally, a covering of surface grime and aged varnish cloaked the original color and composition in an obscuring brownish haze. Intervention was critical to stabilize and return the work to its best appearance. In this three-part series, I will unveil the treatment I undertook on our new acquisition, A Mexican Symphony, and illustrate the methods and principles of contemporary paintings conservation.

–Brandon Finney, NEH Conservation Fellow, 2019–2020

Symphony No 1 in Gold and Green (A Mexican Symphony) before treatment, verso highlighting the damaged state of the canvas held together temporarily with tape.

Flaxen and Fragile: Painting on Canvas

Working in the galleries during our pre-COVID-19 Conservation in the Galleries program, I learned that many visitors are surprised to learn that a painting is not a static object. A painting is often nothing more than a thin piece of fabric upon which paint is applied. The mastery of painting is taking this simple support and transforming it into a work of art. Just like the everyday fabrics we encounter and use throughout our lives, the fabric of a painting receives wear and tear and becomes increasingly fragile as it ages. Most often, canvases are made of linen (flax), hemp, or cotton. These fabrics start life flexible and strong but over time become stiff and brittle. Once a canvas has aged a few decades, it has little resistance to physical damage. In fact, it is exceedingly rare to find an Old Master painting on canvas that is without structural repair.

When A Mexican Symphony came to the Chrysler Museum, it was apparent the painting had been damaged by physical impact. A large section of the canvas had been torn out, leaving two detached fragments. Several other small punctures dotted the same corner of the canvas. Along the edges, where the canvas folded over the stretcher, the fabric had split in several places. The painting was at great risk of further damage and deterioration if no intervention was taken to stabilize the failing canvas.

A Mexican Symphony, before treatment.

A Mexican Symphony, before treatment. Fragments were temporarily held in place for photography.

Controversial Conservation: The Lining of Paintings

In the past, when a painting like this had such severe damage, a lining would be applied. Lining is the centuries-old traditional method to fix a failing canvas. Restorers would remove the painting from its wooden stretcher and laminate an additional canvas on with adhesive. Traditional linings used a mixture of animal glues, resins, and wheat flours as glue, giving them the nickname “pasta linings.” After glue is troweled on, restorers would apply pressure and heat to adhere the new canvas, gluing in place any tears and fragments and thereby stabilizing the aged canvas. The new canvas is strong and flexible enough to endure the tension of re-stretching the work back onto the wooden support.

Lining remains a mainstay of the treatment of paintings but has experienced a dramatic decrease in its use since the 1980s due to its risks and drawbacks. The application of heat and pressure during lining has irreversibly damaged many paintings by flattening and even melting heat-sensitive paint. Along with this heat and pressure, solvent or water found in the glue is forced into the canvas and paint layers. In response, the canvas may shrink or buckle, and soluble components may be pushed to the paint surface where they obscure in the image. Even the glue itself may cause issues; infused into the canvas and paint layers it has the potential to forever darken the appearance of a painting. All-in-all it sounds like a risky gamble, but the lining of paintings has allowed for the near miraculous survival of many centuries-old images, painted on a mere piece of fabric.

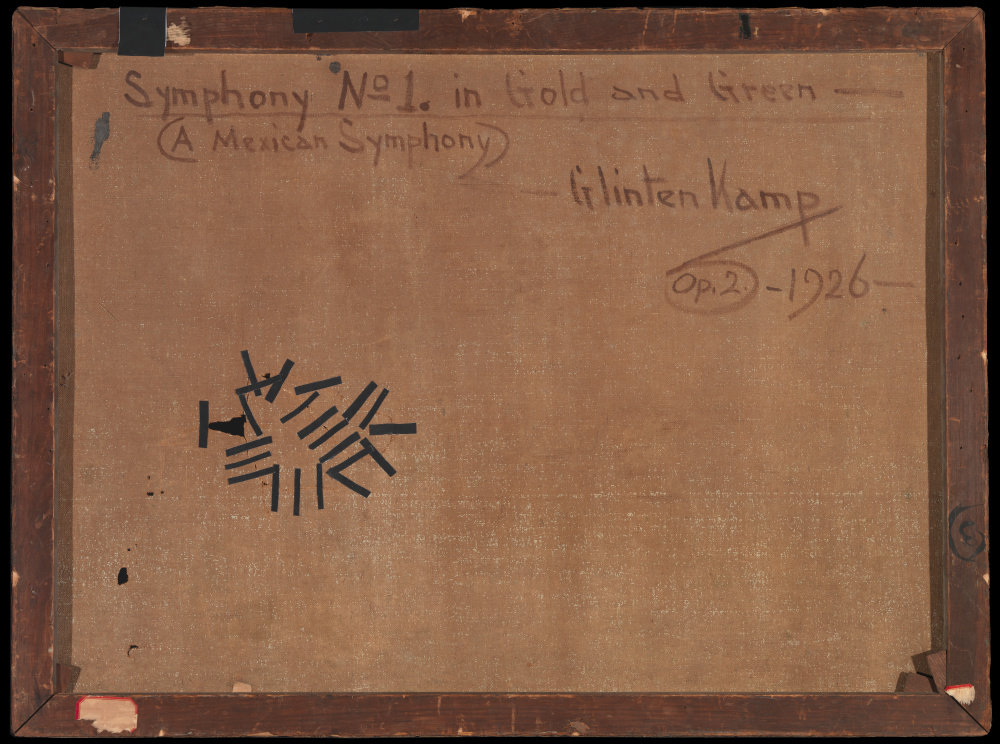

The reverse of a canvas before and after lining.

When it came to the treatment of A Mexican Symphony, one further consideration had to be made; the addition of a new canvas to the reverse of the painting would forever hide Glintenkamp’s original inscription. Most linings are undertaken with opaque fabrics made of linen or white polyester (the kind used for making sails). The addition of these new canvases dramatically alters the appearance of an aged painting, as seen in the images below.

Threading the Needle: The Surgical Repair of Canvases

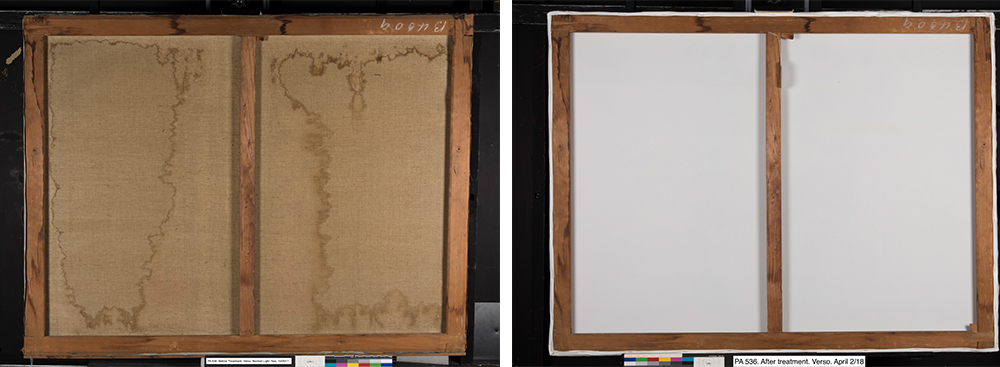

Tools for repair: Needle-tip from a heated spatula, dental tools, and a very fine brush. Thumb for scale. A surgical scope for working under – the same used for heart surgeries.

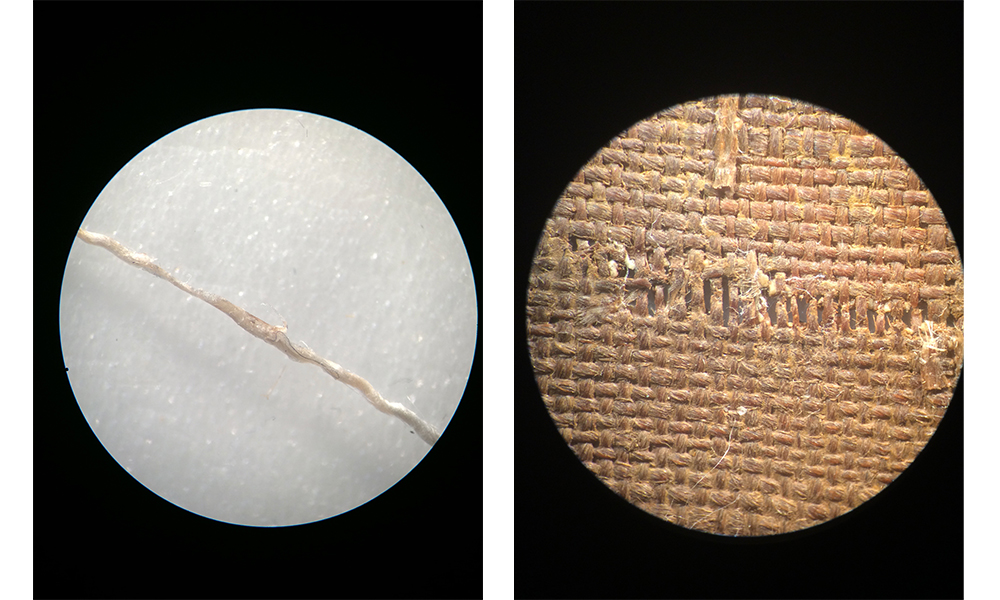

Because of the practical and ethical issues with linings, conservators have increasingly sought alternative methods that can repair and stabilize paintings with minimal change to the original structure. The concept of minimal intervention is one that guides the current practice of art conservation; less is always more and all treatments should be reversible, if possible. These principles ensure that the work we undertake today preserves the object in its original state as much as possible, and furthermore, that the work can be undone or retreated in the future without causing further harm to the original object. When it comes to canvas repairs, tears can now be mended locally under magnification with the aid of a surgical microscope. Using dental and surgical tools, the canvas fibers are realigned as they were originally and the canvas rejoined. A micro-drop of adhesive is applied with a very fine needle before the bond is heat-set with a needle-tip heated spatula. With the proper magnification and a great deal of skill and patience, young cotton canvases with fibers that are still flexible can even be rewoven along tears, resulting in a nearly seamless repair.

Rejoining of two new canvas fibers under magnification. Detail of tear repair on aged canvas – rejoining of highly aged fibers together.

Bridging the Gap: Repairing A Mexican Symphony

For aged canvas like that of A Mexican Symphony, the fibers are too brittle to be rewoven and require the addition of new fiber to bridge the tear. Japanese tissue paper is often used for this purpose. Although it may sound like a weak choice for repairing a tear, the paper has very long fibers that impart it much more strength than the tissue you would find in gift bags. Additionally, being a plant fiber like the original canvas, the tissue and canvas behave similarly when flexed or exposed to fluctuating humidity. Using these fibers ensures the original canvas can still move and react as a whole, not restricted by the addition of a stronger or stiffer material that could cause the canvas to buckle or break around the repair when stressed. Old, heavy patches can often cause these issues, resulting in a bulge where the repair is undertaken, as seen in this late nineteenth-century portrait before its conservation in 2019.

An example of a historical tear repair using an overly large and stiff patch. In raking light, the resulting bulge is highly apparent. Artist Unknown, Portrait of an Old Woman, Oil on Canvas, 0.5673, Before Conservation.

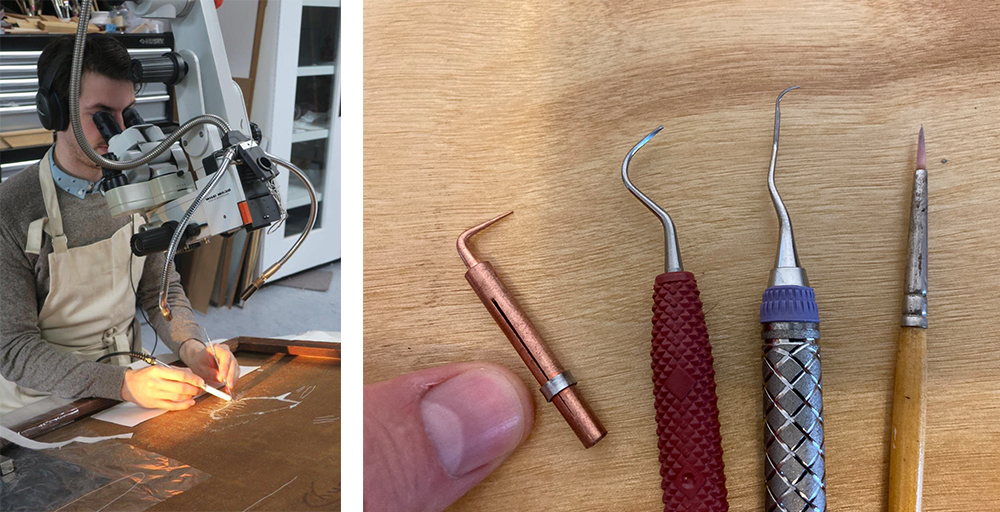

Repairing the tears in A Mexican Symphony required immense planning and precision. Using fine dental tools, a minimal amount of tissue was worked into the tear along with adhesive—a mixture of sturgeon glue modified with wheat starch paste. While it might sound odd, the mixture is both traditional and scientifically tested. Fish glue, in this case high-quality sturgeon glue, is a strong, tacky, and stiff adhesive—excellent for quick and strong bonding. Wheat starch paste is a weaker but more flexible adhesive. It’s also a thick gel that will not wick away in the canvas fibers but stays right where it is placed. A mixture of both glue and paste imparts an adhesive of more ideal properties: strong enough to bond; quick to tack; flexible; easy to control; and most importantly, archival and readily reversible.

Tear repair in progress using a heated needle and dental tools.

Once the tears were bonded with this tissue and glue mixture, I adhered an additional thin patch of Japanese tissue and a grid of linen threads. This gentle reinforcement ensures the canvas once again can support itself and withstand the tension of being stretched.

Detail of repair. Front and back after repair.

With the painting now stabilized, it is ready for cleaning. In part two, Mastic and Mire: The Cleaning of Painting, we will explore how conservators employ contemporary chemistry to remove grime and varnish from the surface of a modern painting.