- Open today, 10 am to 5 pm.

- Parking & Directions

- Free Admission

Walter P. Chrysler, Jr. and the Business of Collecting

–Jeff Harrison, Chief Curator Emeritus

Jean Chrysler at North Wales, Vogue Magazine, April 15, 1948

In 1948, Vogue magazine published an article on North Wales, Walter and Jean Chrysler’s country estate near Warrenton, Virginia. Purchased by Walter in 1941, North Wales had become a showplace for the smart set in the years around World War II, when a “Who’s Who of racing and horse experts” regularly gathered to see Walter’s yearlings bound for Saratoga. The article duly described the house, grounds, stables, and horse track but focused particularly on the Chryslers’ “spectacular” collection of modernist paintings by Pablo Picasso, Georges Braque, and Henri Matisse, many of which were on view at North Wales. “Mr. and Mrs. Chrysler own the most important collection of Picasso’s work in America,” the article proclaimed, encompassing “forty-five oil paintings by the artist and another forty-nine watercolors and drawings,” along with fifteen paintings by Braque and twenty-two by Matisse.

Walter himself would later weigh in on the size of his Picasso holdings, claiming that at one time, he owned an astounding 347 works by the artist. Though no doubt impressive and probably unequaled, we will likely never know the exact size of Walter Chrysler’s modernist art holdings. He was a notoriously secretive man who took pains to obscure his collecting tracks. He also had a flair for exaggeration. It is probably more revealing and instructive to note what became of that collection, for by the mid-1980s, it was all but gone—all but one Picasso painting, one Braque, and one Matisse. By then, Walter had sold or traded virtually all of his modernist art, which had increased exponentially in value, to build the equally extraordinary collection today belonging to the Chrysler Museum of Art. (The three paintings mentioned above were folded into that collection.) Simply put, he swapped one collection for another, with World War II as his pivot point. Why he did this tells us a good deal not only about Walter Chrysler’s motives as a collector but also about the shifting dynamics of art collecting and cultural taste in the decades after World War II.

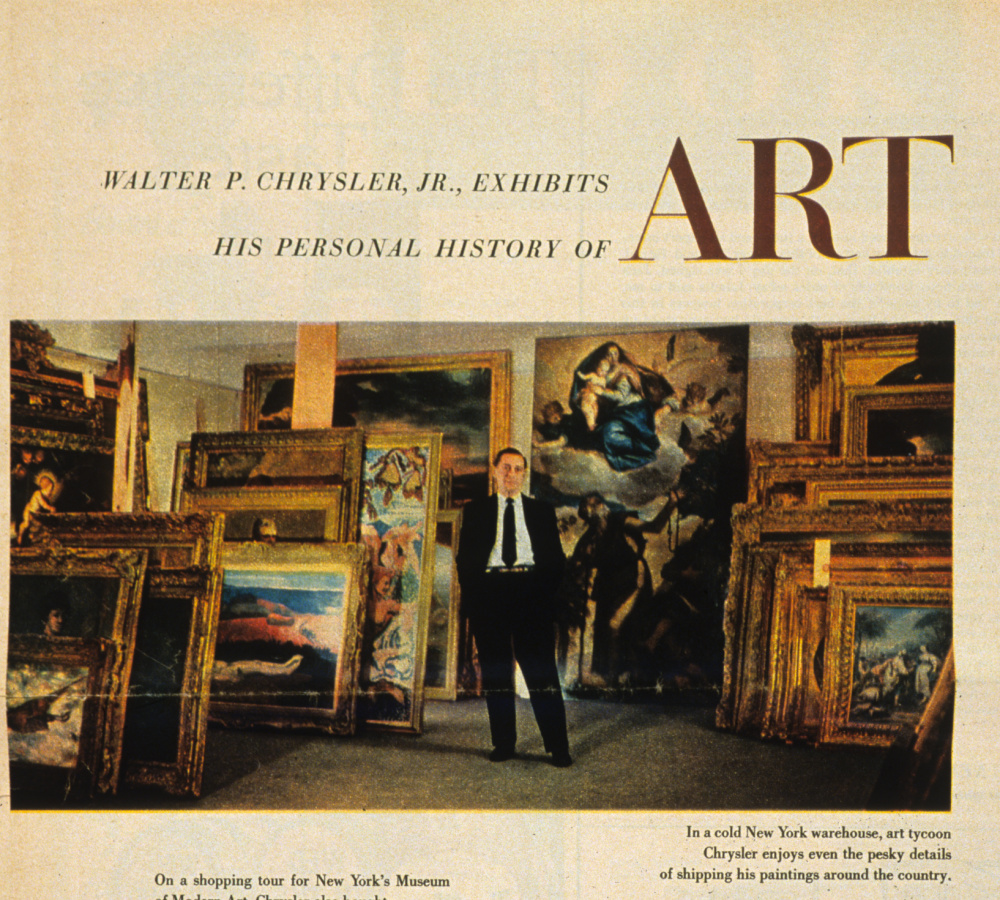

Walter P. Chrysler, Jr., ca. 1950

The war was indeed a pivot point, especially for once-wealthy Europeans and their storied private art collections. Facing post-war economic depression and the staggering burden of inheritance taxes (also called death duties), European and particularly British aristocrats often had little choice but to sell off their portable assets, including their works of art. Scores of Europe’s finest private collections of Old Master paintings began to break up, their contents sold to counter the financial stresses of the war. As a result, major ancestral collections in England, France, and Italy—collections filled with historic masterpieces that had been out of circulation for hundreds of years—were now coming on the block. Walter had purchased a handful of Old Masters before World War II, among them the Museum’s Basket of Plums by Jean-Simeon Chardin. But Europe’s post-war Old Master market was unprecedented both in its scope and stellar level of quality. It was a once-in-a-century buying opportunity, and Walter Chrysler jumped at it.

Paolo Veronese (Italian, 1528-1588), The Virgin and Child with Angels Appearing to Saints Anthony Abbot and Paul, the Hermit, 1562, Oil on canvas, Chrysler Museum of Art, Gift of Walter P. Chrysler, Jr., in Memory of Della Viola Forker Chrysler, 71.527

Many American collectors of the day used the opportunity to buy examples from what, by then, had become a standard set of European art trophies—English portraits, Italian Renaissance paintings, and Dutch Golden Age pictures. Walter seemed at first to follow suit with his post-war purchase of a small but select group of Northern and Venetian Renaissance paintings. His 1954 acquisition of Paolo Veronese’s magisterial altarpiece depicting The Virgin and Child Appearing to Saints Anthony Abbot and Paul, the Hermit represented the highpoint of that effort.

Giovanni Francesco Barbieri, called Guercino (Italian, 1591–1666), Samson Bringing Honey to His Parents, ca. 1625–26, Oil on canvas, Chrysler Museum of Art, Gift of Walter P. Chrysler, Jr., in honor of the Board of Trustees, 1977–1985, 71.521

But ultimately, he was much more interested in what, at the time, was a far less fashionable and thus more affordable subset of the Old Master market: the Italian Baroque. Between 1950 and 1958, he acquired dozens of major seventeenth- and eighteenth-century Italian Baroque paintings, including masterworks by Guido Reni, Giovanni Francesco Barbieri (called Guercino), Bernardo Cavallino, Salvator Rosa, Luca Giordano, Giuseppe Maria Crespi, and Giovanni Battista Pittoni. Many of these works had only recently been auctioned in London from distinguished English private collections. Guercino’s Samson Bringing Honey to His Parents was sold from the collection of the Dukes of Bedford at Woburn Abbey, where it had been for nearly 200 years.

Salvator Rosa (Italian, 1615–1673), The Baptism of the Eunuch, c. 1660, Oil on canvas, Chrysler Museum of Art, Gift of Walter P. Chrysler, Jr. 71.525

Rosa’s Baptism of the Eunuch was sold from the collection of the Earls of Ashburnham, who had owned it since 1812. They were snapped up by art dealers like David Koetser and Julius Weitzner, who funneled them to Chrysler in New York. How important were these paintings to Europe’s historic sense of self? Soon after the Rosa left England, The Times of London published anguished letters lamenting its loss to the nation.

As scholar Edgar Peters Bowron has noted, the 1950s “Golden Age” of Italian Baroque collecting would pass soon enough. By the mid-1960s, many more American collectors had entered the market and prices had risen accordingly. As he had done with his Picassos in the 1930s, Walter had once again recognized the value of an important but underappreciated segment of the art market before it was widely discovered, and he had used his insight to buy early, cheaply, and well. His prescient ability to recognize and profit from unfashionable but worthy markets would become a cornerstone of his collecting mythology. As Walter himself later proclaimed, he regularly collected “against the trend” of the moment and profited from that strategy every time. “I never followed convention.”

Walter collected a range of other historic European paintings during the 1950s, from English pictures by Thomas Gainsborough and David Wilkie to Spanish works by Claudio Coello and Francisco de Zurbaran. But he was especially drawn to French Old Master and nineteenth-century paintings, acquiring a major suite of works from the Baroque and Rococo—including significant works by Nicolas de Largillière and Francois Bouçher—to Impressionist and Post-Impressionist masterpieces by Pierre-Auguste Renoir, Alfred Sisley, Paul Gauguin, and Paul Signac.

Walter and his collection featured in Look magazine, 1956

Indeed, by the mid-1950s, Walter had dramatically ramped up his collecting process. Flush with cash from the sales of his modernist art, he was now buying historic European paintings in massive amounts and at break-neck speed. A 1956 Look magazine article featuring him and his collection proves the point. In the article, Walter appears in his Manhattan warehouse standing amid scores of historic European pictures, all of them recent purchases. By now, of course, he had given up any pretense of working in the family auto business to devote himself wholly to the “business” of collecting art. The article aptly described his newfound vocation, proclaiming him an “art tycoon.” In fact, Walter would soon be aiming to build an encyclopedic collection worthy of its own museum, and the Look article’s title—”Walter P. Chrysler, Jr., Exhibits His Personal History of Art”—seems to foreshadow that grandiose ambition.

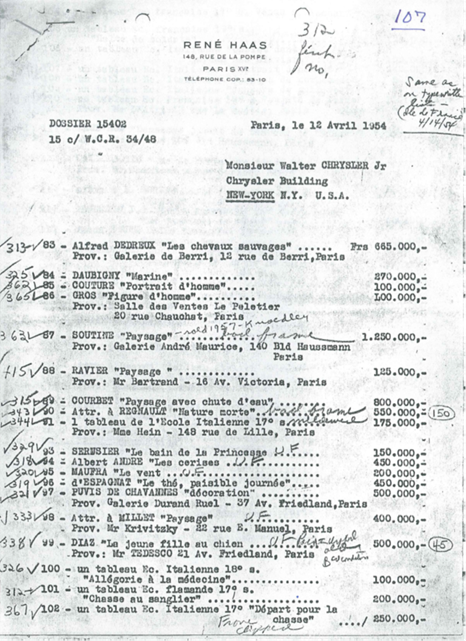

Export Document, Rene Haas, Paris, 1954

A document from the same period—one of the rare surviving pieces of paper that escaped Walter’s studied neglect of record-keeping—offers additional proof of his voracious appetite for historic European art after World War II. It is an invoice and export document compiled by the Parisian art dealer and agent Rene Haas. It is dated April 12, 1954 and addressed to Monsieur Walter Chrysler Jr., Chrysler Building, New York, NY, USA. The invoice runs for four single-spaced typewritten pages and lists more than 100 paintings recently acquired by Chrysler in France. One hundred-plus paintings on a single invoice!

Pierre-Auguste Renoir (French, 1841–1919), The Daughters of Durand-Ruel, 1882, Oil on canvas, Chrysler Museum of Art, Gift of Walter P. Chrysler, Jr. in memory of Thelma Chrysler Foy, 71.518

Walter often faced stiff competition and dizzying price tags when vying for nineteenth-century French art. This was especially true for Impressionist and Post-Impressionist paintings, which were highly prized by American private collectors and public institutions and which consequently brought top dollar at sale. Walter’s acquisition of Renoir’s Daughters of Durand-Ruel illustrates his willingness to pay dearly when the opportunity warranted it. Walter’s sister Thelma Chrysler Foy had acquired the painting in 1944 from the cash-strapped Durand-Ruel family in Paris, and Walter deeply admired it. Thelma died of leukemia in 1957, and two years later, the painting went on the block as part of her estate sale at the Parke-Bernet auction house in New York. Walter disliked buying at auction, preferring to acquire privately through art dealers. Nevertheless, he persevered. At the time of the sale, he secreted himself in a room just off the auction hall, the door cloaked by a curtain, and bid for the painting by telephone. He was successful at $255,000, an extraordinary amount for a work of art in the late 1950s.

Adolphe William Bouguereau (French, 1825–1905), Orestes Pursued by the Furies, 1862, Oil on canvas, Chrysler Museum of Art, Gift of Walter P. Chrysler, Jr., 71.623

At the very moment he was buying prize pieces by Impressionists like Renoir, Walter was searching for worthy bargains by their contemporaries. He found them among the Impressionists’ polar opposites, the so-called French Academic painters. These guardians of the venerable French aesthetic tradition championed, among other things, a tight, flawlessly realistic painting style over the “undisciplined daubs” of the “upstart” Impressionists. Yet, despite the Academics’ efforts to defend and prolong the conservative French Grand Manner, their art was soon eclipsed by Impressionism and other avant-garde movements. By the mid-twentieth century, they were woefully out of fashion. American collectors of the 1950s and ’60s shunned their paintings, and critics of the day dismissed their work as “empty and false,” as the tail end of a long-exhausted artistic tradition. When their names were mentioned at all, one critic said they were “whispered like dirty words.” Undeterred, the prescient Chrysler sensed both the aesthetic and historic import of the Academics, and with prices at rock bottom, he was able to acquire a collection of extraordinary Academic pictures for next to nothing during the 1950s and ‘60s. They included Adolphe-William Bouguereau’s spectacular Orestes Pursued by the Furies, Jean-Léon Gérôme’s lyrical Excursion of the Harem, and Gustave Doré’s near-hysterical vision of life behind the monastery wall, The Neophyte. And just how inexpensive were these paintings at the time Walter was buying them? When The Neophyte was auctioned at Christie’s, London in 1964, it was all but ignored in favor of other works in the sale. It was quietly purchased by a London dealer for a paltry twenty-five pounds (approximately $650 today). Even with that dealer’s inevitable mark-up, Walter likely bought it for a song.

Gustave Doré (French, 1832–1883), The Neophyte (First Experience of the Monastery), ca. 1866–1868, Oil on canvas, Gift of Walter P. Chrysler, Jr. Chrysler Museum of Art, 71.2061

By the 1970s, scholars and critics had begun to reassess and revalue Academic painting as a critical component of nineteenth-century French art, as a key element in the complex interaction of traditional and progressive forces that gave rise to French modern art. Newly reconsidered, the market for Academic pictures revived, their prices steadily rose, and today the hammer prices for Bouguereau, Gérôme, and other Academics are typically stratospheric. Once more, Walter Chrysler discovered a realm of great pictures that were still great bargains.

Frederick Childe Hassam (American, 1859–1935), At the Florist, 1889, Oil on canvas, Gift of Walter P. Chrysler, Jr., dedicated by the Museum Trustees to Linda H. Kaufman in gratitude for the time, talent, and resources she has so generously given to the Chrysler, June 1999, Chrysler Museum of Art, 71.500

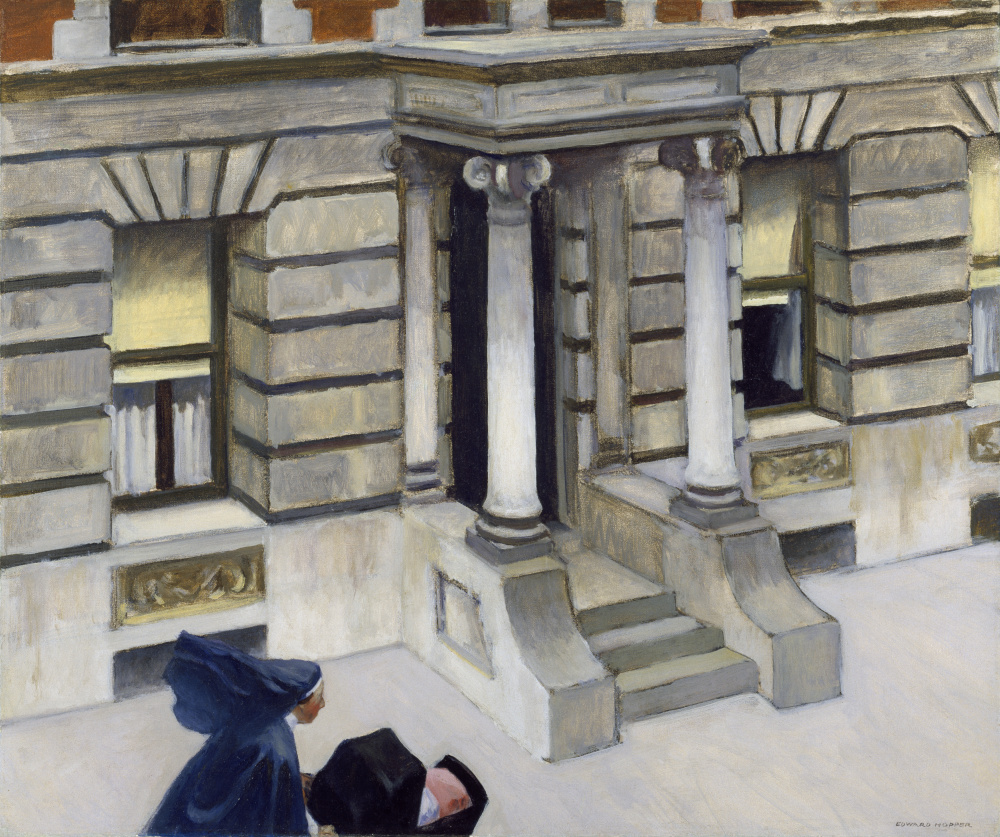

In the late 1950s, as his dream of establishing a Chrysler Museum began to crystallize, Walter ramped up his collecting efforts even more and greatly expanded his field of play. Beginning in 1957, at the very moment he was amassing hundreds of European works of art, Chrysler began to collect classic American paintings of the eighteenth, nineteenth, and early twentieth centuries, again in substantial quantities and at a dizzying pace. His earliest purchases in this area included masterworks such as William Glackens’ The Shoppers and Childe Hassam’s At the Florist. He would go on to build a comprehensive collection of historic American paintings, from colonial-era portraiture to the American scene pictures of Edward Hopper and Thomas Hart Benton. He did much of this at just the time that classic American painting was being critically reassessed, when it was shedding its traditional definition as mere Americana or antiques and being revalued as fine art. Prices for American painting would soon begin to soar. Once again, Walter was able to take advantage of an emerging market before it priced him out.

Edward Hopper (American, 1882–1967), New York Pavements, 1924, Oil on canvas, Chrysler Museum of Art, Gift of Walter P. Chrysler, Jr., 83.591

In 1958, Walter, at last, established a museum in his name, the Chrysler Art Museum in Provincetown, Massachusetts. Provincetown had long nurtured a vibrant artist colony that drew thousands of artists every summer, especially from New England and New York. By the late 1950s, it had also become a summer mecca for the most vanguard members of the post-war New York School. Now settled in Provincetown, Walter could directly and informally engage with avant-garde giants like Hans Hoffmann and Franz Kline. He could live among them and watch them work. Walter had not been this close to the creative hurly-burly of actual art making since his encounters in the 1930s with Picasso and company in Paris, and the experience must have delighted him. Provincetown gave him the opportunity to engage once more with the art of the new, and may well have prompted his pre-war love of French modernism to evolve into a post-war love of American modernism. In any event, it was precisely at this moment that he began to acquire contemporary American art both in Provincetown and New York, including examples of Abstract Expressionist, Pop, and Color Field painting. In the process, he expanded his historic American collection to include cutting-edge contemporary works by Hans Hoffmann, Franz Kline, Jackson Pollock, James Rosenquist, and Roy Lichtenstein, among many others.

Franz Kline (American, 1910–1962), Zinc Yellow, 1959, Oil on canvas, Gift of Walter P. Chrysler, Jr., Chrysler Museum of Art, © The Franz Kline Estate / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York, 71.666

Roy Lichtenstein (American, 1923–1997), Live Ammo (Ha! Ha! Ha!), 1962, Oil on canvas, Chrysler Museum of Art, © Roy Lichtenstein Foundation, 71.676

Walter’s devotion to the decorative arts was already apparent in the 1940s in the interiors of North Wales, where he boldly accented his modernist paintings by Picasso and Matisse with classic English and continental silver and furniture. Silver would remain an abiding passion in the decades after the war, when he gathered a remarkable array of American and European pieces, among them William Christmas Codman’s spectacular Martele Centerpiece of 1904.

William Christmas Codman, designer (English, 1839–1921), Gorham Manufacturing Company, Providence, Rhode Island, Martelé Centerpiece, 1904, Sterling silver, Gift of Walter P. Chrysler, Jr. 78.128

In the area of furniture, Walter’s taste would shift after World War II to embrace the French Art Nouveau. When he was buying Art Nouveau material in the 1950s, it was yet another undervalued aesthetic brimming with bargain masterpieces. He and Jean filled their homes in Provincetown and, later, in Norfolk with extraordinary French Art Nouveau furniture by Émile Gallé and Louis Majorelle. They literally lived among pieces like the Majorelle Console Desserte.

Louis Majorelle (French, 1859-1926), Console Desserte, ca. 1900, Mixed woods, ormolu and mother-of-pearl, Gift of Walter P. Chrysler, Jr., 83.546

After Jean suddenly passed away in 1982, Walter had the furniture removed from their Norfolk house and gifted it to the Museum, where it is currently on view today in its own gallery in the European wing.

Tiffany Gallery, Chrysler Museum of Art, May 2014, photograph by Ed Pollard, Museum Photographer

The most expansive of Walter Chrysler’s passions within the realm of the decorative arts was for glass. His love of glass began in his youth, much of which was spent at King’s Point, the Chrysler family’s estate on the North Shore of Long Island. King’s Point was just down the shore from Laurelton Hall, Louis Comfort Tiffany’s fabled estate near Oyster Bay, and we know that the young Chrysler met Tiffany there in 1931, toward the end of the great glass artist’s life. The encounter, which likely inspired Chrysler to make early purchases of Tiffany glass, made a lasting impression on him. He later lauded Tiffany as “one of the most creative and imaginative taste-makers the United States has produced.” Walter’s interest in American glass expanded after 1958 when he established his museum in Provincetown and became enamored of local New England glass production. It was then that he began buying masses of glass made by the famed Boston & Sandwich Glass Company and the Mt. Washington Glass Company. Indeed, over the next fifteen years, he bought glass in massive quantities and at near-light speed, and as he had done with painting, he applied an expansive, encyclopedic impulse to collecting it.

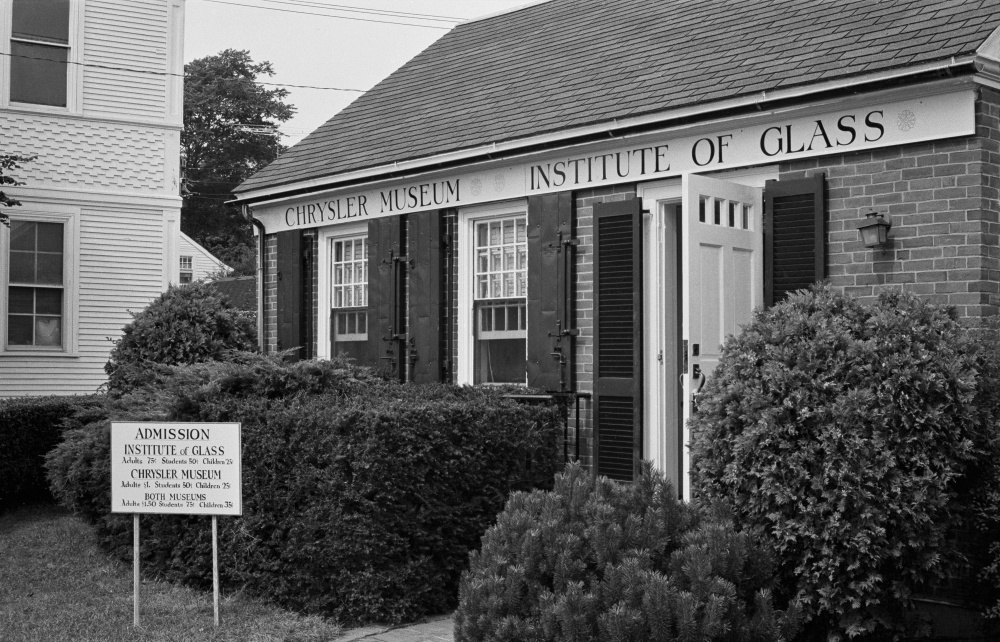

Chrysler Museum Institute of Glass, 1968, Provincetown, Massachusetts

By the time Walter arrived in Norfolk in 1971, he had assembled a glass collection of nearly unrivaled richness and variety, a collection of some 10,000 objects stretching from rare ancient Egyptian and Islamic vessels to heart-stoppingly beautiful American and French art glass of the early twentieth century. He had built, quite literally, a museum within a museum, one that boasted a special concentration of Art Nouveau glass by Tiffany, from his windows and lamps to lava glass, jack-in-the-pulpits, and flowerform vases. Walter bought much of his Tiffany when it was still very much a bargain. He even collected antiquities, from the art of ancient Egypt to that of Greece and Rome.

Eugène Delacroix (French, 1798–1863), Arab Horseman Giving a Signal, 1851, Oil on canvas, Gift of Walter P. Chrysler, Jr., 83.588

When Walter arrived in Norfolk in 1971, he was sixty-two years old. His mad-cap collecting career was largely behind him, though he still made regular forays to New York galleries to find new pieces for the museum in Norfolk. In later years, he focused strategically on “completing” the Museum’s collection, adding singular works by important artists who had eluded him in the past or works that would fill critical gaps in his “personal history of art.” With those goals in mind, he acquired unique European treasures like Georges de La Tour’s Saint Philip and Eugène Delacroix’s Arab Horseman Giving a Signal. He snagged equally critical American pieces, chief among them John Singleton Copley’s Portrait of Miles Sherbrook, Thomas Cole’s The Angel Appearing to the Shepherds, Albert Bierstadt’s The Emerald Pool, and Mark Rothko’s No. 5 (Untitled).

Thomas Cole (American, 1801–1848), The Angel Appearing to the Shepherds, 1833–34, Oil on canvas, Gift of Walter P. Chrysler, Jr., in memory of Edgar William and Bernice Chrysler Garbisch, 80.30

In later years, Walter also worked to persuade other collectors to make block donations to the Chrysler. While he had collected American folk paintings in the 1930s and ‘40s, he soon realized that his sister and her husband, Bernice and Col. Edgar William Garbisch, were doing a far better job of it than he, and so he ceded the field to them. Ever mindful of their extraordinary holdings, beginning in 1975 he convinced the two to donate more than 150 of their American folk paintings to the Museum.

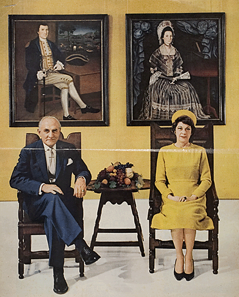

Col. Edgar William and Bernice Chrysler Garbisch, Look magazine, 1962

In the 1980s, Walter persuaded Norfolk doctor Edwin Pearlman to donate a large portion of his rare holdings of Maya ceramics, which serves today as the highlight of the Museum’s gallery of Mesoamerican art. And in 1986, Walter helped to finalize a deal with James Ricau, the savvy collector of nineteenth-century American marble sculpture that brought his entire collection of seventy sculptures to the Chrysler. In a single stroke, the Museum became home to one of the finest collections of nineteenth-century American sculpture in the country.

Gallery 105, Mesoamerican Gallery, May 2014, photograph by Ed Pollard, Museum Photographer

James H. Ricau Gallery, 1998-2014, Chrysler Museum of Art

Walter Chrysler became increasingly frail in his final year, and on September 17, 1988, he passed away at Sentara Norfolk General Hospital. He was seventy-nine years old. The stated cause of death was prostate cancer. Norfolk’s city attorney had been scheduled to meet with him in the hospital to have him sign a new will, last updated in 1979. The proposed amendments would have stipulated that all works of art remaining in Walter’s private collection, either on loan to the Museum or in New York, were to come to the Chrysler upon his death. Unfortunately, Chrysler died before the city attorney could meet with him. That left the 1979 will in place. While it stipulated a few important loans as bequests to the Museum, it directed that the overwhelming majority be left to Walter’s nephew, Jack Forker Chrysler, Jr., who had no relationship with the Museum and quickly readied the art for sale.

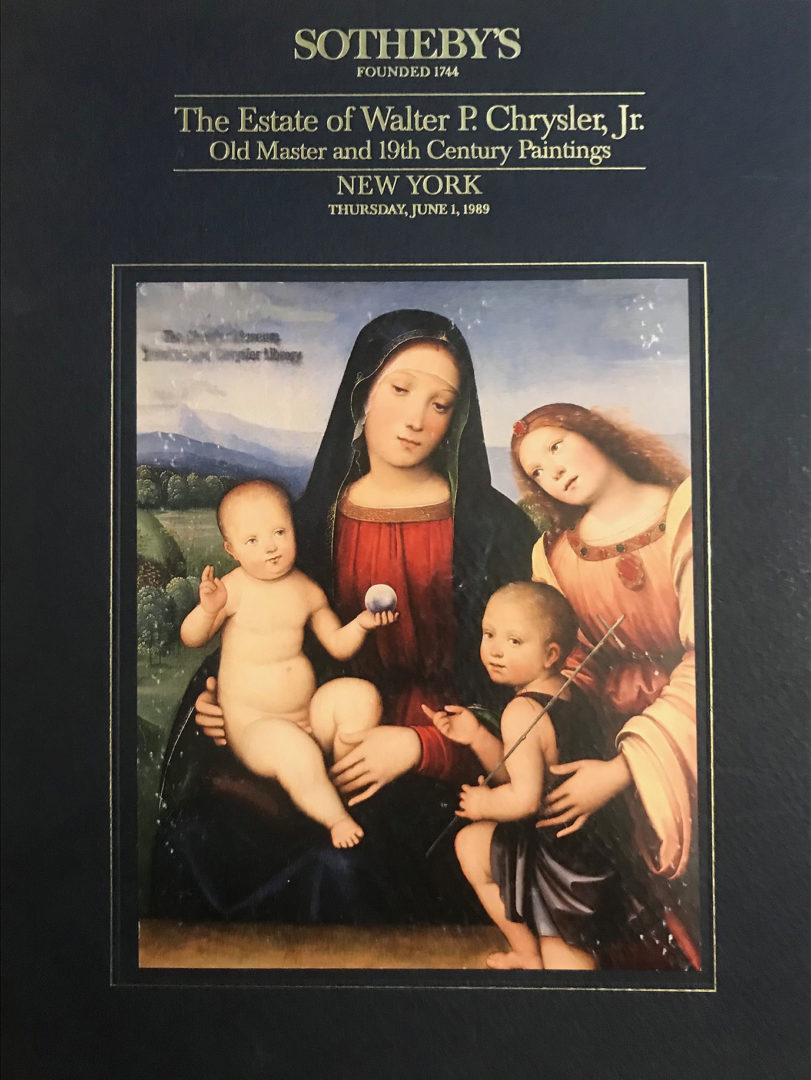

Catalogue, Walter P. Chrysler, Jr. Estate Sale, Sotheby’s, New York, June 1, 1989

The most publicized of those Chrysler estate sales was the June 1, 1989, auction at Sotheby’s, New York, where 128 paintings from Walter’s collection—Old Master and nineteenth-century European works— went on the block. The Museum also lost a key group of Art Nouveau and Art Deco objects, including a number of rare Tiffany lamps. The bulk of that material went to auction a few weeks later on June 16. The Museum staff was deeply disappointed by the loss of those works. Many had been on loan to the Museum for years and would have played key roles in the grand reopening of the newly expanded and reinstalled Museum in February 1989.

Walter P. Chrysler, Jr., ca. 1980, Chrysler Museum of Art

Yet despite that loss, the overwhelming majority of Chrysler’s post-war collection and all of the great masterpieces within it had already been gifted to the Museum. Walter had gathered most of them — tens of thousands of objects — in a mere twenty years, from the 1950s to the 1970s. Many American private collectors of his generation had tended to focus their energies and hone their interests on an ever tighter and finer concentration of treasures. But Walter continued to gather massively and simultaneously on multiple fronts, buying masterful examples of European and American painting, sculpture, drawings, silver, furniture, glass, and antiquities all at once. He purchased the objects in a great rush, in a kind of creative fury that we, in retrospect, still struggle to closely map or document for all the dust it raised.

Chrysler Museum of Art, 2014, photograph by Ed Pollard, Museum Photographer

We are reminded of the term “art tycoon,” which suggests a person who applies the rough and tumble of the corporate world to the normally decorous and deferential realm of art collecting, a person who possesses qualities like wealth and power, to be sure, but also heroic energy, aggressiveness, split-second decision-making, and, of course, shrewdness and cunning. Someone who constantly surveys the horizon for any and all opportunities for gain, who values speed, volume, multiple targets. All of this defines Walter Chrysler the collector and his quest to create a genuine museum of art. His gift to us—to Norfolk, Hampton Roads, Virginia, and the nation—was, quite simply, an astonishment, one of the richest, most varied, and most visionary gifts ever bestowed upon an American museum. So as we mark the fiftieth anniversary of his arrival in Norfolk and his initial donation to the Chrysler Museum of Art, we invite you to raise a glass to a one-of-a-kind American collector and his extraordinary legacy. Three cheers for Walter P. Chrysler, Jr!

**For a full account of Walter P. Chrysler, Jr.’s life and collecting career, see particularly Peggy Earle’s excellent Legacy: Walter Chrysler Jr., and The Untold Story of Norfolk’s Chrysler Museum of Art, University of Virginia Press, Charlottesville and London, 2008; Jefferson C. Harrison et al., Collecting with Vision: Treasures from the Chrysler Museum of Art, D. Giles Limited, London, 2007; Eric M. Zafran and Edgar Peters Bowron in Buying Baroque: Italian Seventeenth-Century Paintings Come to America, Frick Collection, New York, 2017; Diane C. Wright, ed., Glass, Masterworks from the Chrysler Museum of Art, University of Washington Press, 2017; and Vincent Curcio, Chrysler: The Life and Times of an Automotive Genius, Oxford University Press, Oxford and New York, 2000.