- Open today, noon to 5 pm.

- Parking & Directions

- Free Admission

Walter P. Chrysler, Jr: A Legacy

–Jeff Harrison, Curator Emeritus

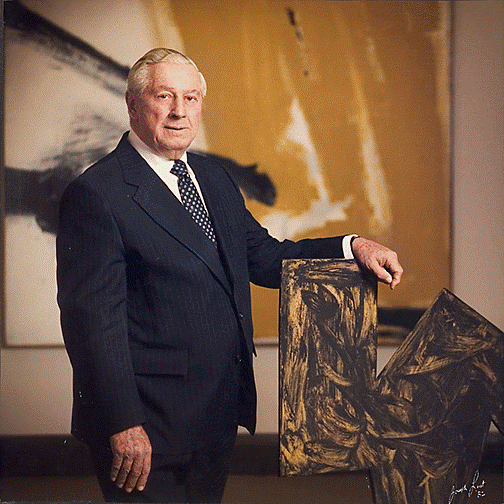

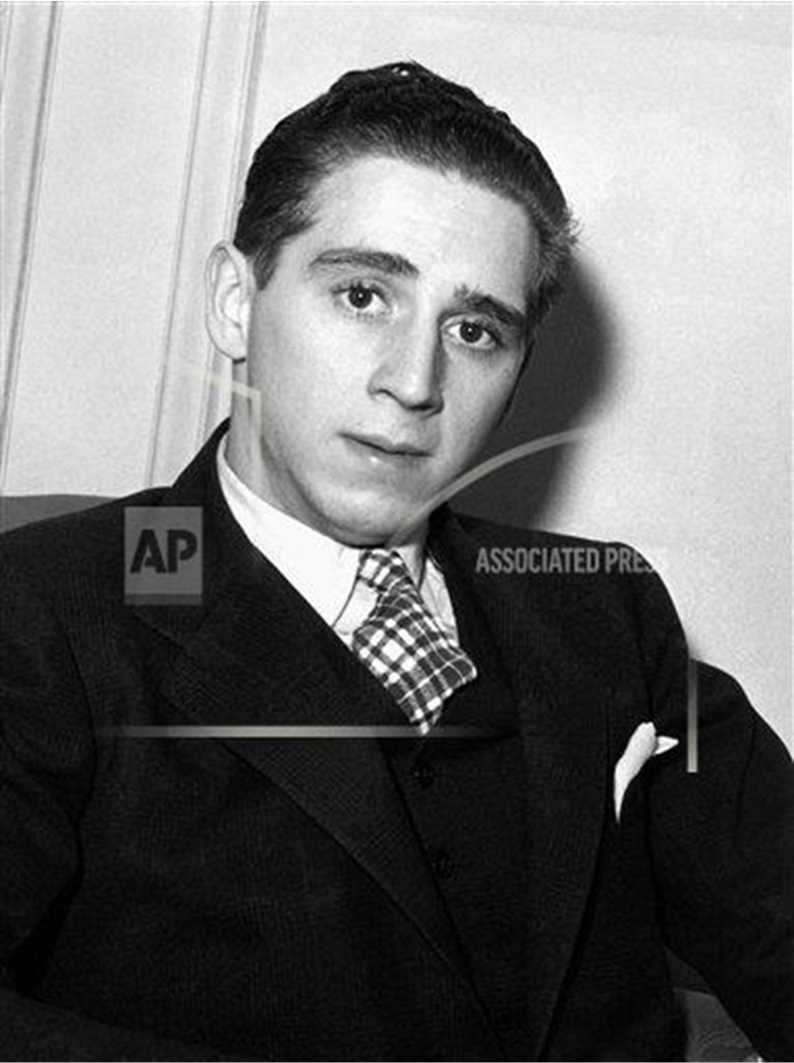

Walter P. Chrysler, Jr. © Joseph Lust

Walter P. Chrysler, Jr. is celebrated today as one of the most influential art collectors and benefactors of the twentieth century. A major figure in the New York art scene both before and after World War II, Chrysler achieved his most enduring fame beginning in 1971, when he began a series of spectacular art donations that transformed the modest Norfolk Museum of Arts and Sciences into a cultural powerhouse, the Chrysler Museum of Art. Given his larger-than-life achievement as an art collector and donor and the place it earned him in the history of American collecting, one might assume that, from the beginning, he devoted himself solely to the world of art. Yet Chrysler faced a series of competing expectations during his early years that centered on his place in one of America’s most prominent families and the business empire it created. The story of how the young Chrysler came to terms with those demands is key both to his evolution as a man and art collector and to his ultimate emergence as the principal donor of the Chrysler Museum of Art. The story begins here and will expand over the course of future blogs.

Young Walter P. Chrysler, Jr, 1910s.

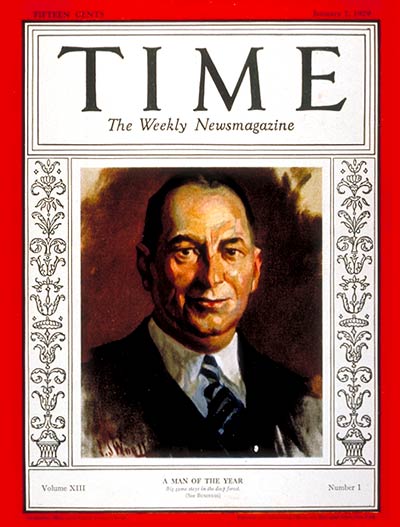

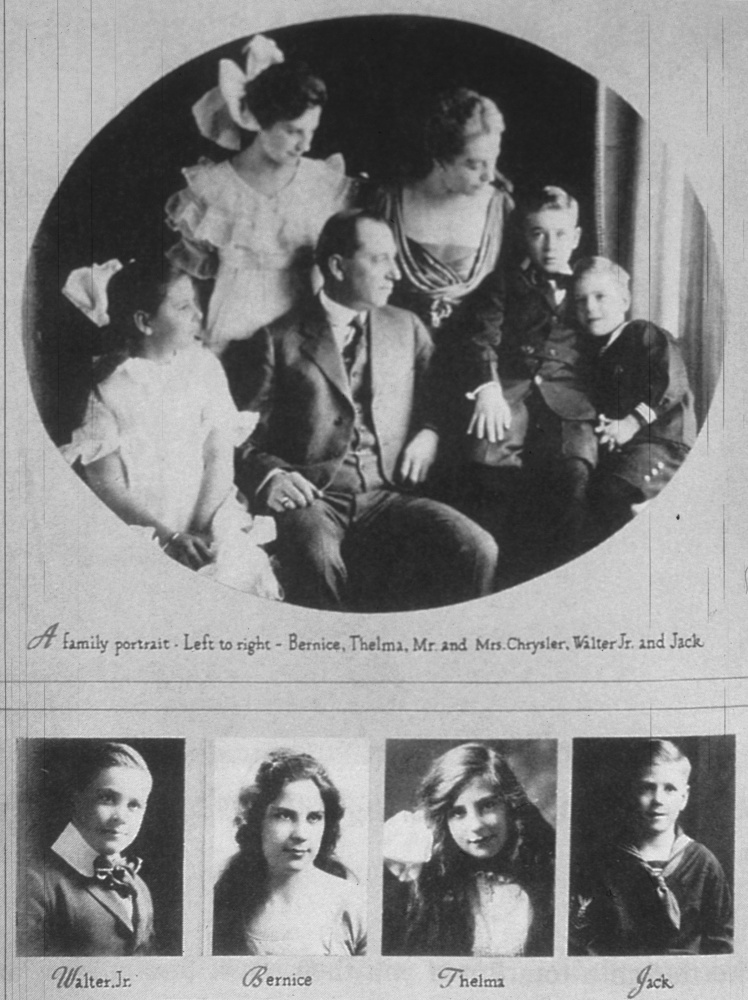

Walter Percy Chrysler, Jr. was born on May 27, 1909 in a small white-frame house in Oelwein, Iowa. He was the third of four children born to Walter P. Chrysler, Sr., and his wife, Della Viola Forker Chrysler. His two sisters, Thelma and Bernice, were older than he, and his younger brother John (Jack) was born three years after him in 1912. Though Chrysler Sr. began work as a master mechanic for the Chicago Great Western Railroad, his brilliance as a businessman assured his rapid rise within the broader American corporate world. He quickly moved from the railroads to the new and booming auto industry. As he ascended in his career, his family moved with him from Iowa to Pittsburgh to Flint, Michigan. By 1925, he had founded his own car company, the Chrysler Corporation, and had brought out the first Chrysler automobile, establishing himself as one of the most innovative American industrialists of the first half of the twentieth century.

Chrysler Sr. as Man of the Year, Time magazine, 1929

By then, the family had settled in New York City, where they lived in a grand apartment at 289 Park Avenue on Manhattan’s Upper East Side. They bought a summer estate, King’s Point, near Great Neck on the North Shore of Long Island. The house would ultimately become part of the campus of the United States Merchant Marine Academy at King’s Point. The family also had a winter home in Palm Beach. The Chryslers’ rise to the rarefied heights of polite society was assured in 1926, when their name was added to the list of elite families in the New York Social Register.

Chrysler Family Portrait

This formal family portrait from about 1920 reflects the Chryslers’ newfound affluence and growing social expectation. Walter Jr. sits with his brother Jack on his parents’ left, and all eyes turn to them. Below, in the cameos of the four children, Walter is given pride of place at the far left at the head of the line, as it were, reflecting his position as the elder son and his father’s namesake. Presumably, he was already yoked with dynastic yearnings and expected to continue in Walter Sr.’s path, to enrich and expand his father’s legacy as a businessman and corporate leader.

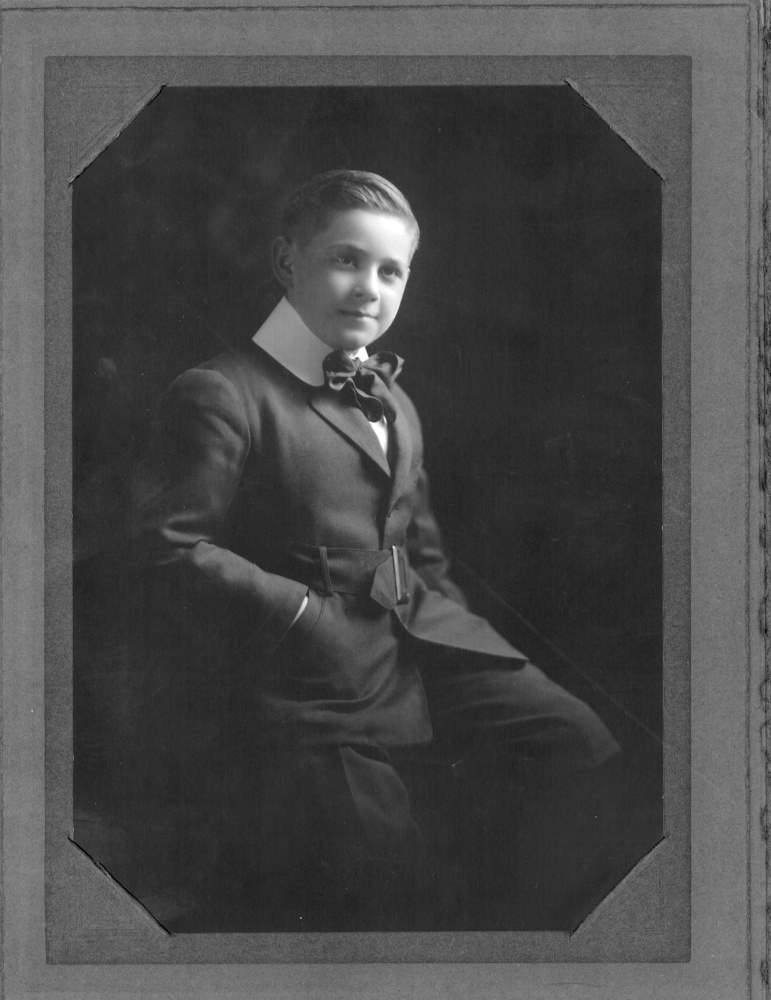

Walter Chrysler, Jr., ca. 1919

Walter’s early years brimmed with privilege. His parents enrolled him in a succession of prestigious private schools, beginning with the Browning School in Manhattan. He went on at age fourteen to the Hotchkiss School in Lakeville, Connecticut, and finally in 1929 to Dartmouth College in Hanover, New Hampshire. At the end of his second year, Walter withdrew prematurely due officially to complications from a bleeding ulcer, an affliction that plagued his childhood. Following his departure from school, he visited Europe and especially Paris at his mother’s behest. The trip would prove a revelation, offering the young American, then barely twenty-two years old, his first full encounter with the intoxicating world of French modernist art. It launched his obsession with the modern School of Paris and began an intense decade-long buying spree (1931–1941) focused particularly on the paintings of Pablo Picasso and his fellow Cubists.

After Hugh Ferriss (American, 1889-1962), Chrysler Building, 1929, Gelatin silver print, Walter P. Chrysler, Jr. Art Purchase Fund, 2007.4

Despite that head-spinning event, upon Walter’s return to New York, his father urged him to settle into the family business. As Walter Sr.’s elder son and namesake, one might expect the young Chrysler to have jumped at the chance to prove himself and work to join his father at the helm of the family’s newly constructed skyscraper headquarters, the Chrysler Building, at Lexington Avenue and 42nd Street. His brother Jack would, in time, do just that. More socially adept and gifted at business than Walter, Jack was apprenticed as a Chrysler machinist at age twenty-two and would eventually make a solid mark at the corporation. He would go on to form a venture capital company with a Chrysler associate and become a broker with coveted seats on both the New York and American Stock Exchanges. Surely Walter felt some pressure to get a head start on his younger sibling in the family enterprise, and for a time in the mid-1930s, he seems to have tried to do that.

Walter P. Chrysler, Sr. and Walter P. Chrysler, Jr., ca. 1930

In 1934, Walter was named chairman and president of Chrysler’s Temperature Corp. This put him in charge of the company’s innovative Air Temp division, which by the 1940s led to the creation of the first air-conditioning system for automobiles. While some have argued that Walter acquitted himself well in the job, others have questioned just how active he was in the day-to-day running of the enterprise, suggesting that it was his father who actually controlled the operation. In any event, Walter resigned from the job in 1935 and soon after was offered the position of president of the Chrysler Building. Here, Chrysler Sr. applied an “Horatio Alger” challenge to his son’s corporate rise, demanding that he literally start at the bottom of the building, in the purchasing department, and learn the intricacies of the entire business on his way up to the executive suite. Walter followed his father’s course and in 1936 became president of the W. P. Chrysler Building Corporation. Yet his lofty title seems to have obscured what was essentially an empty, figurehead position, one that Walter Sr. created to keep an eye on his unpredictable son and make sure he could “do no harm.”

There was good reason by then for his father to worry. Walter had neither the head nor heart for business. Instead, he nurtured a far more vital passion for the world of the arts, collecting ever-growing masses of contemporary French paintings and embarking on a series of other arts-related projects that often brought the family considerable consternation.

Walter Chrysler, Jr. ca. 1930

At Dartmouth, for example, Walter ignored his academic studies—including a course in business administration—to devote his time to collecting art, antiques, and rare books. He set himself up in an apartment off campus, where he hosted champagne-laced art “salons” for fellow students. Such activities raised eyebrows at the insular New England college long known for its macho ethos. But Walter’s art ventures did allow him to meet an interested member of the senior class, Nelson Rockefeller, elder son of the industrialist John D. Rockefeller, Jr. Chrysler Sr. and John D. had long been friends, and one might have expected Walter to see in Nelson a valuable future colleague and contact in the corporate world. In fact, it was Nelson’s artistic and literary activities at the college that most attracted him, leading the two to collaborate on the publication of a campus literary magazine, The Five Arts. Walter quickly went on to found his own publishing company, Cheshire House, which produced a number of luxury volumes for well-heeled bibliophiles. It was headquartered right under his father’s nose, on the fifty-seventh floor of the Chrysler Building, and though it won literary awards, it soon collapsed in a shower of unpaid bills. One volume alone was rumored to have racked up nearly $38,000 in losses, which Chrysler Sr. presumably had to cover. (Two years later, in 1932, Walter would open his own commercial art gallery, the Cheshire, on the ground floor of the Chrysler Building.) All of these extracurricular ventures came at a cost to his college career. By the end of his sophomore year, he had distinguished himself in only one course, philosophy, and had stopped going to class altogether. Soon after, he withdrew from Dartmouth.

Walter and his sister Thelma, 1930s

Walter’s attempt to find his place in elite Manhattan society would also prove problematic, though in the early 1930s it looked promising enough. He is first mentioned in the Social Register in 1929 and would establish himself as a member in good standing in a raft of elite clubs and other organizations, among them the New York Yacht Club, the New York Athletic Club, the Dartmouth Club, the Madison Square Garden Corporation, and the exclusive Greek Club on Long Island. He even joined the Sons of the American Revolution.

Wedding of Walter P. Chrysler, Jr. and Marguerite (Peggy) Sykes.

The final step in his social ascent was to make an advantageous marriage. His sisters had already preceded him to the altar, and the expectation from the family and patrician Manhattan society that he too would marry, and marry well, must have been considerable. In any case, on April 29, 1938, in the chapel of St. Bartholomew’s Church in New York, Walter married a twenty-five-year-old Manhattan socialite named Marguerite Prince Sykes, called Peggy, who was breathlessly described in the press as “the most sought-after girl in New York society” and a “veritable dream bride.” Yet despite its apparently auspicious beginning, the marriage quickly floundered. On the heels of their honeymoon in Paris—which Walter used to buy more art and to introduce Peggy to Pablo Picasso, Gertrude Stein, and the rest of the city’s avant-garde—Walter’s beloved mother, Della, died. Just weeks before that, his father had suffered a stroke that would plague him until his death two years later. Just as Walter was trying to establish his own emotional independence, his principal mainstays were vanishing. To complicate matters on the homefront, Peggy had absolutely no interest in modern art. She openly disliked Picasso’s paintings and refused to sit for him for her portrait. (She later quipped that she did not want to have “five noses and six eyes.”) Yet far more critical was their basic emotional and sexual incompatibility. Peggy found her new husband to be cold and foul-tempered, and the relationship quickly soured. She lasted a mere eighteen months until October 1939, when she traveled to Nevada to get a speedy Reno divorce. The stated reason for the split was “extreme cruelty,” but almost certainly the marriage was never consummated. More than likely, Peggy had realized what had long been an open secret about Walter Chrysler at Hotchkiss and Dartmouth, in Europe and New York, and in his own family: he was gay. As Vincent Curcio observed in his biography of Walter Sr., in the 1930s “there was enormous pressure on gay men to marry and give the appearance of living a ‘normal’ life.” Walter probably hoped that Peggy would accept a marriage of convenience in return for the wealth and prestige that came with the Chrysler name. She refused. Walter would remain closeted for the rest of his life.

Walter and Thelma at Walter Sr.’s Funeral

Barely thirty years old, Walter thus found himself surrounded by losses and uncertainties. He had failed to find a secure and meaningful foothold in the family business and had lost a chance at conventional social respectability through marriage. He had also lost both parents, but with that came opportunity. Della’s death in 1938 left her four children a modest estate of roughly $20,000. Walter Sr.’s death in 1940 left much more, nearly $9,000,000, to be evenly divided among his offspring. Walter’s inheritance, roughly two and a quarter million dollars (about $40,000,000 today), hardly matched the assets of a Vanderbilt or Rockefeller. Yet it was more than enough to give him genuine financial independence and freedom of choice—and ultimately the opportunity to begin a life devoted entirely to art. After 1940, he began a series of withdrawals from New York to follow his new life. He continued to focus his collecting in Manhattan and kept his Upper East Side apartment and his art storage warehouse on Charles Street to facilitate it. Yet he spent more and more time away—first in Virginia horse country, then in Provincetown, Massachusetts, and eventually in Norfolk. Step by step, he loosened his grasp on Manhattan and the constraints of his former life there.

North Wales

Thus, in April 1941, he spent $175,000 to buy a 1,100-acre estate and horse farm called North Wales near Warrenton in northern Virginia. The house, dating from the eighteenth century, was immense. Among its seventy-two rooms was a ballroom, trophy room, and hunt room. The surrounding estate was equally grand. In addition to the requisite horse stables and training track, the grounds featured a golf course, lake, and even a private airfield. Chrysler had dabbled before in horse racing, and he ostensibly set himself up at North Wales as a country gentleman intent upon horse breeding and racing and showcasing his spectacular French modernist collection. On the other hand, he may have bought the place principally as a tax shelter to protect his inheritance.

Walter P. Chrysler, Jr. at North Wales

North Wales was also a short commute to Washington, DC, where government jobs could be had. With World War II and the newly instituted draft looming in America, Walter may have hoped to avoid conscription and, at the same time, burnish his reputation with a prestigious civilian war-time job with the federal government. In June 1941, he applied for a position in the Washington Office of Production Management. The Office was designed to convert peacetime industries, like America’s auto industry, to wartime needs. Walter may have thought that his Chrysler name and experience, such as it was, would make him a viable candidate. Following standard government procedure for wartime job applicants, the FBI opened a confidential investigation into his “character, reputation, qualifications, loyalty, patriotism, and his political affiliations.” The file, which was recently made public, makes for grim reading. While interviewees affirmed his patriotism and his Republican voting record, most leaned in hard on his failures as a businessman, his explosive temper, and his “moral degeneracy”—his gayness. Needless to say, he did not get the job. In April 1942, soon after America entered the war, a thirty-two-year-old Walter Chrysler, Jr. was suddenly awarded a Navy commission, entering the service as a lieutenant junior grade. Almost certainly the family did a deal and got him in.

Walter Chrysler, Jr. and Jean Chrysler, 1940s.

Walter was first posted briefly to Norfolk and soon met Jean Esther Outland, an attractive, young Norfolk woman who, some say, was introduced to him at a party at the Cavalier Hotel in Virginia Beach. Their budding relationship was interrupted when he was transferred to Key West. If the many images of Walter in uniform are any indication, he was clearly proud of his appointment. Nevertheless, his naval career was troubled and short-lived. In December 1944, under investigation at the Washington Office of Naval Intelligence, he abruptly resigned his commission and left the service. Rumors eventually flew about raucous, possibly gay parties in his rooms off base. Walter attributed his resignation to a disqualifying medical condition—another of his bleeding ulcers. In any case, the facts of his dismissal would never be known since the Navy’s file on the matter simply disappeared. One senses again the Chrysler family and its handlers coming to the rescue, working behind the scenes to avoid a scandal.

Walter and Jean, 1940s

Remarkably, less than a month after his dismissal, Walter returned to Norfolk and, in a quiet ceremony in the Freemason Street Baptist Church, married Jean Outland. Jean may have lacked the social cachet of a New York debutante like Peggy Sykes, but she offered her new husband crucial qualities that he desperately needed: loyalty, stability, and what proved to be an enduring commitment to his central passion: art. She became a genuine partner in his lifelong quest to collect. She settled with him at North Wales and in New York, moved on with him to Provincetown, and in 1970-71 returned with him to Norfolk. There, she devoted the final decade of her life to the Chrysler Museum and a host of other local cultural initiatives. Her death came suddenly in 1982 when she succumbed to complications of a stroke. She was sixty years old.

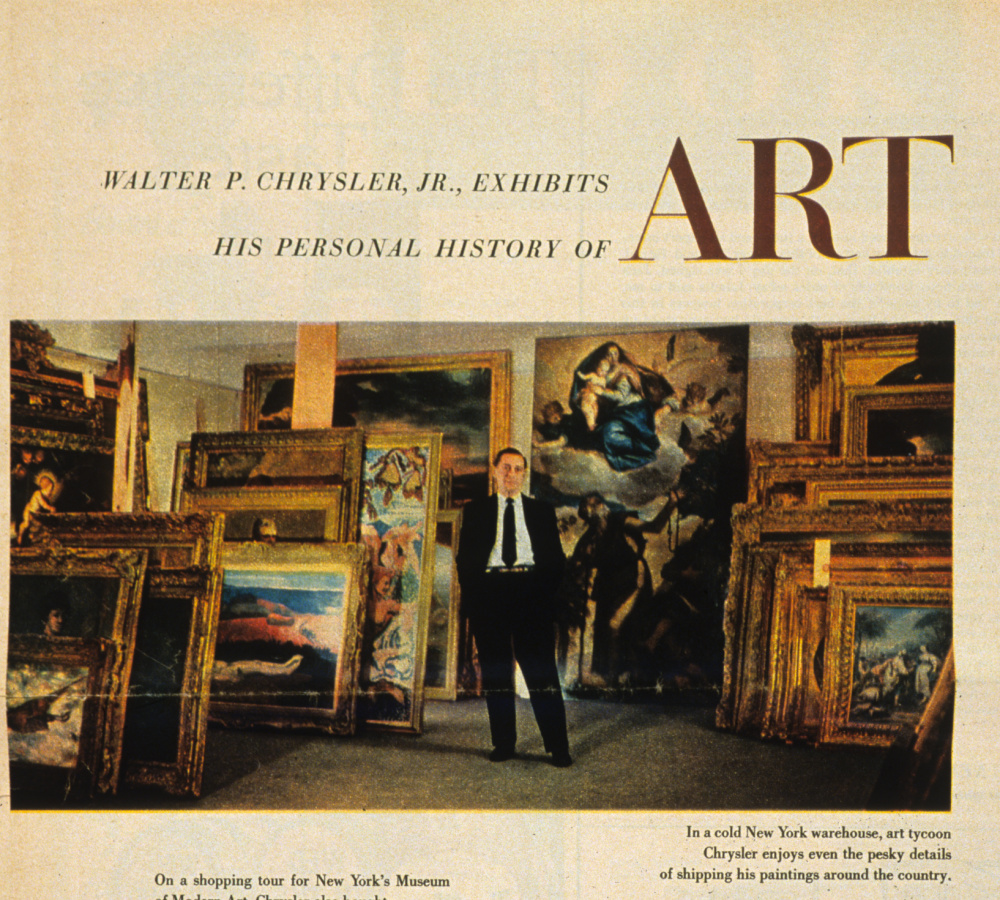

Walter and his collection featured in Look magazine, 1956

After World War II, Walter’s collecting interests and methods fundamentally changed. It was then that he all but abandoned his earlier passion for French modernism and began to collect a much broader range of art forms, which he amassed in astonishing numbers and at extraordinarily high velocity. Gathering massively and simultaneously on multiple fronts, he acquired everything from European Old Masters, nineteenth-century French paintings, and historic and contemporary American art to Art Nouveau furniture, American and European silver, and an incomparable collection of glass. He even collected Egyptian and Roman antiquities. He was now moving beyond the discreet confines of a private collection to embrace the comprehensive, encyclopedic scope of a genuine museum. To bankroll these acquisitions, he sold or traded the bulk of his earlier French modernist collection, relinquishing his pre-War collection to establish a second, larger post-War collection. It was that collection that came to Norfolk in 1971. He also liquidated several of his real estate and Chrysler business holdings. He put North Wales up for sale in 1957 and folded his profits from the recent sale of the Chrysler Building into his art coffers. No longer harboring any illusions of a role in the family business, he resigned as president of the Chrysler Building in 1953. Henceforth, his only “business” would be the collecting of art, and he would sink every dollar he had into buying it.

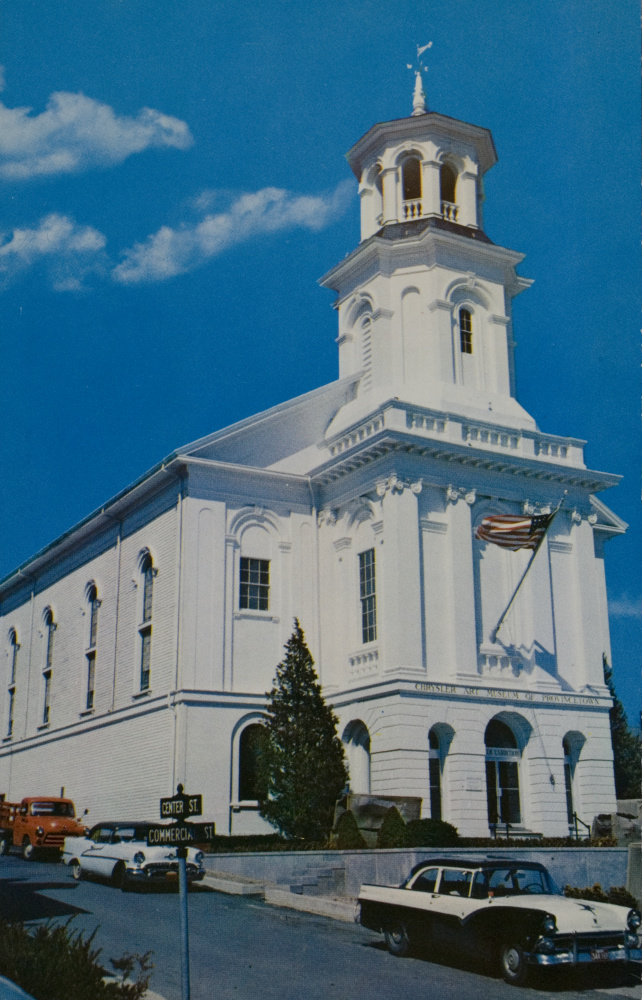

Chrysler Art Museum, Provincetown, MA

Walter’s growing resolve to establish a museum seems to have been prompted in part by a pair of family tragedies. In 1957, Walter’s sister Thelma died of leukemia in Manhattan. She was fifty-five years old. One year later, in 1958, his younger brother Jack died suddenly of a heart attack at age forty-six, leaving Walter the family’s lone male standard-bearer. Both events brought thoughts of mortality and family legacy to the fore and with them a desire to build some sort of personal monument to carry the family name. This is precisely when Walter opened his museum in the small New England coastal community of Provincetown, Massachusetts. He spent $40,000 to buy the town’s defunct Central Methodist Church, which he rapidly renovated and opened in July 1958 as the Chrysler Art Museum. Though the laid-back artist community was a salutary summer venue for the Chryslers, over time, it proved frustrating on a number of fronts. The museum was ultimately too small and cumbersome to house the entire collection. Walter continued to store much of it in warehouses in Manhattan and sent parts of it on the road in traveling exhibitions. And the town council could not meet his escalating demands for community support and municipally-funded improvements to the site.

Norfolk Mayor Roy B. Martin, Jr., with Walter and Jean, Norfolk, ca. 1970

In 1969, he resolved to give up the cramped quarters of his makeshift museum and go shopping for a new and larger home for his art, one that would agree to carry the family name. He embarked upon a national search, vetting more than fifty regional museums from California and Texas to Colorado and Maine. Walter’s decision to move to Norfolk was owed decisively to Jean, who skillfully intervened on her hometown’s behalf. Credit was also due to the city’s mayor at the time, Roy B. Martin, Jr., who saw the collection as the lynchpin in the long-hoped-for revival of the city’s cultural and economic life in the fallow decades after World War II, and who skillfully worked to make the donor a deal he could not refuse. Not everyone in Norfolk was happy with the negotiations. Some objected to the donor’s requirement that the Norfolk Museum be renamed the Chrysler. Others were concerned about Walter’s by-then tarnished reputation. His standing as a collector had indeed been seriously compromised in 1962, when a major traveling exhibition drawn from his collection, The Controversial Century, 1850–1950, was attacked by prominent New York critics and the newly founded Art Dealers Association of America as a show peppered with fakes. (The scandal shadowed him for years and almost certainly hardened his resolve not to settle his collection in New York.) A small group of disgruntled Norfolk citizens even took the city to court to block the deal.

Walter making the deal with Norfolk officials

But calmer heads prevailed, and today the Chrysler Museum of Art is hailed as the artistic cornerstone of a city that has since grown into a regional cultural mecca, one that also serves as home to the Virginia Symphony, Virginia Opera, Virginia Stage Company, and the annual Virginia Arts Festival. Walter arrived in Norfolk intent upon running the museum himself and set himself up as both its president and director. In time, he gradually stepped away, content in the institution’s growing professionalism and stature. He succumbed to cancer in Norfolk on September 17, 1988. He was seventy-nine years old. He was buried alongside Jean in the Chrysler family mausoleum in Sleepy Hollow Cemetery near Tarrytown, New York.

In the years since Walter’s death, the Chrysler Museum has dramatically expanded both its collection and community reach. It unveiled a sweeping expansion and renovation of its building in 2014, and it currently houses more than 30,000 works of art. After World War II, Walter P. Chrysler, Jr. worked tirelessly to build a collection with the range and scope of a genuine museum and then offered that collection to the people. He would no doubt smile broadly at the Chrysler Museum’s institutional commitment to “bring art and people together,” not merely to “enrich” their lives, but quite literally to “transform” them.

**For a full account of Walter P. Chrysler, Jr.’s life and collecting career, see particularly Peggy Earle’s excellent Legacy: Walter Chrysler Jr., and The Untold Story of Norfolk’s Chrysler Museum of Art, University of Virginia Press, Charlottesville and London, 2008; Jefferson C. Harrison et al., Collecting with Vision: Treasures from the Chrysler Museum of Art, D. Giles Limited, London, 2007; and Vincent Curcio, Chrysler: The Life and Times of an Automotive Genius, Oxford University Press, Oxford and New York, 2000.

.