- Open today, 10 am to 5 pm.

- Parking & Directions

- Free Admission

Walter Chrysler in Question: The Controversy of Owning Fakes

–Jeff Harrison, Chief Curator Emeritus

Walter P. Chrysler, Jr., Provincetown, ca. 1960

In June 1962, the Chrysler Art Museum in Provincetown, Massachusetts premiered The Controversial Century: 1850–1950, an exhibition drawn from the collection of its founder and principal donor, Walter P. Chrysler, Jr. Chrysler had organized special exhibitions from his collection for decades and especially in the years around 1958 when he opened his museum on Cape Cod. Drawn from his reported holdings of 3,800 paintings and drawings and 1,000 sculptures and other objects, his Provincetown shows often traveled to other American museums, introducing the Chrysler collection, and the collector, to a broader national audience.

The Controversial Century: 1850–1950, Paintings from the Collection of Walter P. Chrysler, Jr., 1962, exhibition catalog

The Controversial Century: 1850–1950 was an unusually large show with a uniquely ambitious, even grandiose, intellectual premise. It contained 187 paintings and 90 sculptures assembled to trace the complex skein of artistic trends and dizzying array of stylistic “isms” that had marked the past one hundred years and that, together, had given birth to the modern art of the West. Focusing particularly on the art of France, the exhibition included important works from nearly every avant-garde movement of the past century, from the paintings of the mid-nineteenth century Barbizon School and Pre-Impressionists to the Impressionists, Post-Impressionists, the Fauves and Symbolists, and on to the myriad Cubist permutations of Picasso and Braque in the twentieth century. But the show went further, boldly adding the conservative masters of the nineteenth-century Academic tradition to the rich mix of artist-revolutionaries. Paintings by Bouguereau, Jacquet, and Perrault were displayed alongside works by Renoir, Degas, and Gauguin. In that sense, the exhibition was ahead of the art historical curve, admitting the Academics back into the pantheon of critical nineteenth-century tastemakers well before most contemporary art historians were willing to do so. The show made another provocative move by exhibiting nineteenth- and twentieth-century American paintings alongside European art of the same era, suggesting trans-Atlantic stylistic commonalities that had yet to be fully recognized by the scholarly cognoscenti. With this remarkably diverse array of objects, the exhibition attempted to trace the tumultuous clash of artistic theories and styles that led to the triumph of modernism. Hence, its dramatic title.

National Gallery of Canada, Lorne Building, Ottawa, Ontario, 1972, Photo: MBAC Bibliothèque et Archives

The Controversial Century was intriguing enough to capture the attention of an important North American institution, the National Gallery of Canada in Ottawa, Ontario, which signed on to take the show (without the sculptures, which did not travel) after it closed in Provincetown. The exhibition thus became the first (and only) Chrysler collection show to include an international venue. The participation of a plum international venue like Ottawa might at first have seemed a coup for Chrysler, though in time, it proved problematic.

Once open in Provincetown, the exhibition earned favorable notices in the local press and a few brief mentions in the New York papers. But the official stamp of approval came on June 17 when John Canaday, chief art critic for the New York Times, published a glowing review in that paper after seeing the show in Provincetown. His review, titled “Good Exhibition Opens the Season in Art’s Summer Capital,” was as much a paean to the vacation charms of Cape Cod as a critical assessment of the show. Yet Canaday praised the show’s “offbeat inclusions” and its “persistently offbeat character.” He found the Academic and American works refreshing and pronounced the exhibition “an excellent show for any locality.”

Canaday’s review encouraged many more New Yorkers to visit. Among them were the Manhattan collector and lawyer Ralph F. Colin and his wife, who summered in Provincetown and saw the show somewhat differently from Canaday. Indeed, the works Canaday described as interesting “offbeat inclusions” struck them as nothing but trouble. They realized almost immediately that a large number of paintings in the show—perhaps as many as eighty —were fakes, many of which were alleged to be by major masters like Monet, Renoir, and Van Gogh. “They weren’t even good fakes,” Colin later said.

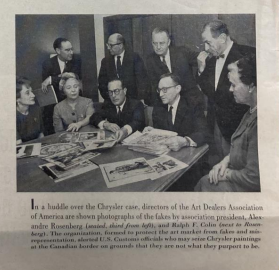

Art Dealers Association of America directors, New York, 1962. Colin is seated, third from the right.

There were few visitors as primed as Ralph Colin to engage with such issues. A trustee of the Museum of Modern Art and a noted collector of contemporary art, he was also the executive vice president of the Art Dealers Association of America (ADAA). He was the organization’s lawyer as well.

Founded in early 1962, the ADAA brought together a group of forty-five elite dealers who began working to codify best practices for the profession and protect the art-buying public from shoddy market practices and shady dealers. Their efforts by then were sorely needed. The commercial art world in America had never been properly regulated, but by 1960, the situation had reached something of a crisis. The post-war years had brought unprecedented affluence to many, creating an expanded collector class and a growing national corp of art dealers to serve them. Yet without proper oversight, the newly crowded and competitive realm of dealers had become increasingly prone to ethical missteps and even blatant illegalities, including everything from making fraudulent appraisals and false object attributions to selling out-and-out fakes. The ADAA proclaimed itself ready to clean up the mess.

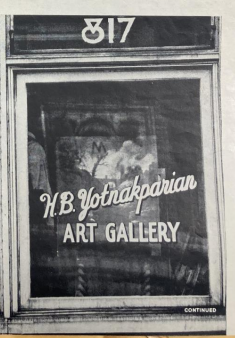

Yotnakparian Art Gallery, New York, 1962

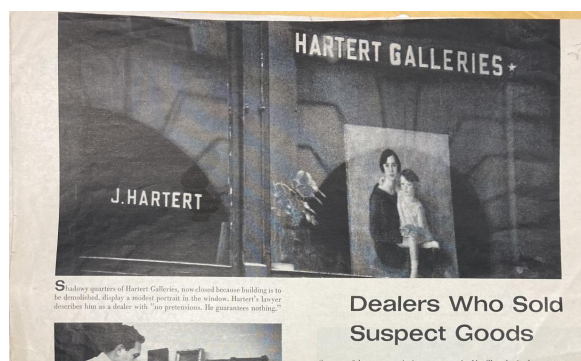

Hartert Galleries, New York, 1962

The entries in the catalog for The Controversial Century indicated that Chrysler had bought virtually all of the suspect works just months before from two Manhattan art dealers, Harry Yotnakparian and Joly Hartert. Both ran small, undistinguished galleries with marginal reputations. Colin immediately sensed malfeasance and alerted the ADAA. With Ottawa ready to take the show, it could become, he warned, “an international art scandal.” The ADAA quickly saw the issue as a crucial first test for the fledgling organization to prove its mettle. Over the summer, it quietly began investigating the two dealers and Chrysler. Colin alerted the National Gallery of Canada that the show contained questionable works, but its director, Charles Comfort, ignored the warning. (He also ignored warnings from his own staff and from Evan S. Turner, then director of the Montreal Museum of Art.)

Walter and Jean Chrysler with Dr. Charles Comfort at the National Gallery of Canada, 1962

The September 27 opening in Ottawa was met with positive press both in New York and Ottawa. The Ottawa Journal published a full-page spread titled “Gallery Scores Another First—$6,000,000 Art Show Brought to Ottawa.” The article described the show as “one of the most comprehensive exhibitions of modern paintings ever seen here, drawn from the world’s biggest private collection.”

With the exhibition now open in Canada, Colin and the ADAA contacted United States Customs and border control agents to be on the alert for the eventual return of the tainted works of art, should they need to be seized and taxed before reentering the country. They alerted other American art dealers and art experts to avoid future contact with the works in question. They even urged the Internal Revenue Service to investigate the Chrysler Art Museum’s tax-exempt status, especially if Chrysler intended to profit from the subsequent sale of the works. The IRS contemplated charging Chrysler with fraud.

Before going public, Colin and the ADAA also informed Canaday of their concerns and urged him to revisit the show. Canaday raced to Ottawa for another look and quickly penned a second and far more critical assessment in the New York Times, one that stopped just short of a full retraction of his first review. “Within this large and fine exhibition,” he wrote, “there is secreted a second and smaller one in which pedigrees are nonexistent or dubious, and attributions are arbitrary to such an extent that, the stylistic evidence being what it is, one must question them.” He blamed his earlier critical myopia in Provincetown on its “intoxicating” summer air and the “ingestion of seafood platters.”

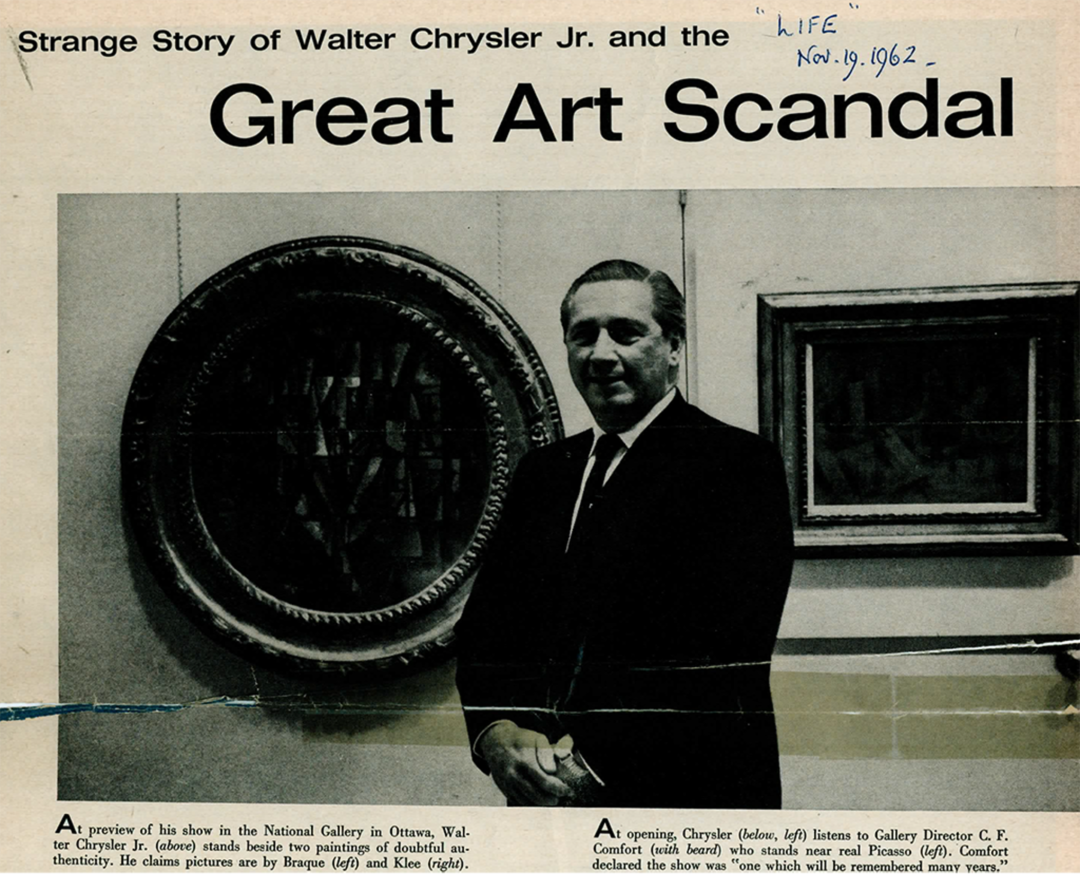

Life magazine, November 19, 1962

With that, the story went viral and quickly made headlines in both Canada and the United States. By November, Newsweek, Time, and Life magazines had all weighed in on the story, calling it an art scandal of international proportions. Embarrassed by the blunder of its national museum, the Canadian Parliament threatened an investigation of its own, including a critical look at the National Gallery’s annual budget. The Gallery’s director of exhibition extension services was soon forced to resign. The ADAA petitioned the office of the New York County district attorney to investigate all suspect dealers in its jurisdiction. The press coyly riffed on the title of the show to report on the “controversy” now surrounding Chrysler and his art.

Despite the uproar, the principals in the story remained officially upbeat or maddeningly evasive. No one apologized or even tried to explain. Gallery director Comfort tried to bluff his way through the scandal by appearing to revel in the exhibition’s sudden notoriety. “We expect we will have even bigger crowds,” he said. “This is the best publicity we could possibly have.” Yotnakparian ducked and weaved, stating that he “guaranteed the period, but never the authenticity of a painting. We never sell anything ‘by’ an artist. How can I? I wasn’t there when he painted it.” Hartert’s lawyer went even further, stating that his client “guarantees nothing.” Publicly at least, Chrysler seemed unfazed. “I am satisfied with all the pictures,” he stated. “I don’t make any claim for their being the greatest examples of each artist, but we can’t look at masterpieces all the time. I think that would be rather dull.”

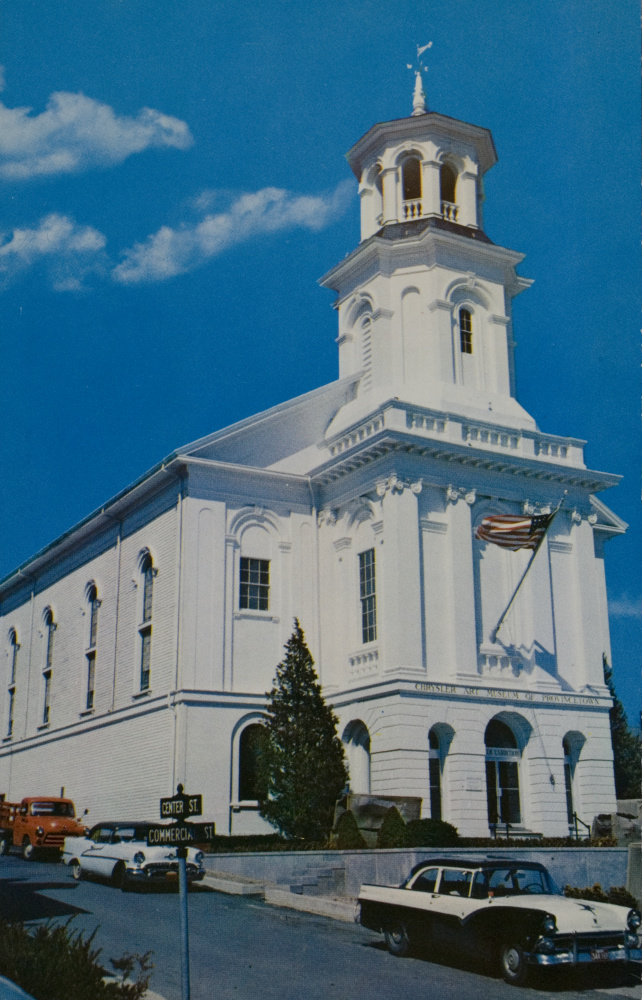

Chrysler Art Museum, Provincetown, Massachusetts, 1960s

And for all the threats of legal action, in the end, there were few genuine consequences. Chrysler’s art, both legitimate and fake, was allowed to cross the Canadian border at the end of the Ottawa venue and returned safely to his museum in Provincetown. (US customs officials dismissed the entire episode as “a tempest in a pot of tea.”) The Canadian Parliament never officially investigated the National Gallery, and Comfort stayed on as director until his retirement in 1965. He was made an officer of the Order of Canada in 1972. Hartert closed his gallery within months of the scandal. His building was demolished shortly thereafter. The seventy-year-old Yotnakparian also faded from view, and the IRS did not revoke the Chrysler Art Museum’s tax-exempt status. The ADAA, of course, emerged triumphant, effectively staking its claim as a force to be reckoned with in the world of art commerce.

Walter Chrysler, Jr. at North Wales

Yet after the debacle of The Controversial Century, Walter Chrysler’s reputation never fully recovered. Why would someone who had amassed tens of thousands of remarkable works of art over the course of thirty years of collecting jeopardize everything with a group of obvious fakes? And do it all so very publicly? What was he thinking? Did he knowingly scheme to seed his collection with bogus pieces, hoping that, through their association with his bonafide art, they would gain legitimacy and increase in value? Many believed that he did.

On the other hand, could it all have been, in some sense, an honest mistake? Chrysler typically collected rapidly and on multiple fronts, and he often bought in bulk, acquiring masses of objects in one go. Could he have been acquiring art so furiously in the early 1960s that he failed to properly vet everything he bought? Chrysler tended to purchase art from dealers rather than at auction, preferring the privacy and bargaining flexibility of a gallery purchase over the publicity and rigid hammer price of an auction sale. Perhaps this made him more vulnerable to the machinations of certain dealers, machinations less likely to occur, perhaps, in a more controlled and closely vetted auction setting. In 1932, just out of college, Chrysler opened his own commercial art gallery, the Cheshire, in the Chrysler Building. Years later, he operated another art gallery on Madison Avenue. From the beginning, then, he seems to have blurred the boundary between the elite realm of art collecting and the more pragmatic, hard-nosed world of art commerce. Could that have led to mixed motives and clouded decision-making? Can an art buyer also be a seller without compromising his own ethical standards?

The Controversial Century was not the first time Chrysler’s name was associated with alleged fakes. In late 1961, the Museum of Modern Art asked him to lend several of his paintings by Pablo Picasso to its upcoming exhibition celebrating the eightieth anniversary of Picasso’s birth. Chrysler offered a half-dozen works to the MoMA show, photographs of which were then sent to the artist in Paris for his approval. Picasso responded by writing “faux”—”false” or “fake”—on two of the photos. When the perplexed MoMA staff asked Chrysler to consider retiring those works from his loan list, he refused, demanding that the Museum display all his works as authentic or forfeit the entire group. MoMA rejected his ultimatum, and Chrysler withdrew everything and walked away. The exhibition, Picasso in the Museum of Modern Art, 80th Birthday Exhibition, opened on May 14, 1962, just weeks before the Provincetown premiere. One is left to wonder if Chrysler also bought the disputed Picassos from Hartert or Yotnakparian.

Harry Yotnakparian’s son Peter displays paintings for a client, Yotnakparian Gallery, New York, 1962

Harry Yotnakparian may have inadvertently offered insight into Chrysler’s thinking around the time of The Controversial Century. When interviewed about the works he sold to Chrysler, the dealer said he simply brought out the paintings for him to examine and let him decide who had done them, assuming that someone with Chrysler’s knowledge and experience knew a Monet or a Van Gogh when he saw one. Could it be, then, that Chrysler himself made the attributions? Could he have reached a point by the 1960s where he had convinced himself of his own infallibility as an art connoisseur? That he alone had the expertise and the critical eye to see what others could not? That he could make truth happen? If so, then the very qualities that had otherwise made him such a formidable and effective collector—his boundless self-confidence, outsized ego, and even his arrogance—had finally betrayed him.

Walter and Jean Chrysler, First Provincetown Arts Festival, Provincetown, Mass. National Open Exhibition American Art of Our Time. July 15th thru Aug 17th. “5 Tents of American Art”

After The Controversial Century, Chrysler resumed his collecting in New York and his museum activities in Provincetown. The fakes were quietly removed from the collection, which remained what it had always been—a vast treasure trove of unquestionably authentic works brimming with masterpieces. He later maintained that the 1962 episode had been largely trumped up by certain dealers in the ADAA as payback for his years of hard bargaining and less than timely payments. (Indeed, he was taken to court more than once for failure to pay his bills.) He went on to acquire more European and American masterpieces, and his collection was still in demand from other institutions. He lent repeatedly, for example, to the influential Finch College shows in Manhattan and to major international loan exhibitions. And in 1969, when he resolved to leave Provincetown and began shopping for a new museum to accept his art, scores of institutions across America reportedly jumped at the chance.

Norfolk Mayor Roy B. Martin, Jr. and Walter P. Chrysler, Jr. finalize the deal

The winning bid, of course, came from the city of Norfolk, Virginia, which offered its Norfolk Museum of Arts and Sciences as the Chrysler collection’s new home. Some residents used the memory of the scandal to scuttle the agreement, warning that the collection might still contain suspect works. They also objected to the requirement that the Norfolk Museum be renamed the Chrysler, and they took the city to court to stop the deal. Others, like Jean Chrysler and Norfolk mayor Roy B. Martin, Jr., took the longer view. They looked beyond the scandal and the collector’s personal flaws and foibles to see the offer for what it was—an astonishing, epoch-changing gift of art that would transform a small provincial museum into a national treasure. Fortunately, they prevailed, and we are all infinitely richer for it.

Chrysler Museum of Art, Photograph by Ed Pollard, Museum Photographer