- Open today, noon to 5 pm.

- Parking & Directions

- Free Admission

Walter P. Chrysler, Jr.’s First World-Class Collection

–Jeff Harrison, Chief Curator Emeritus

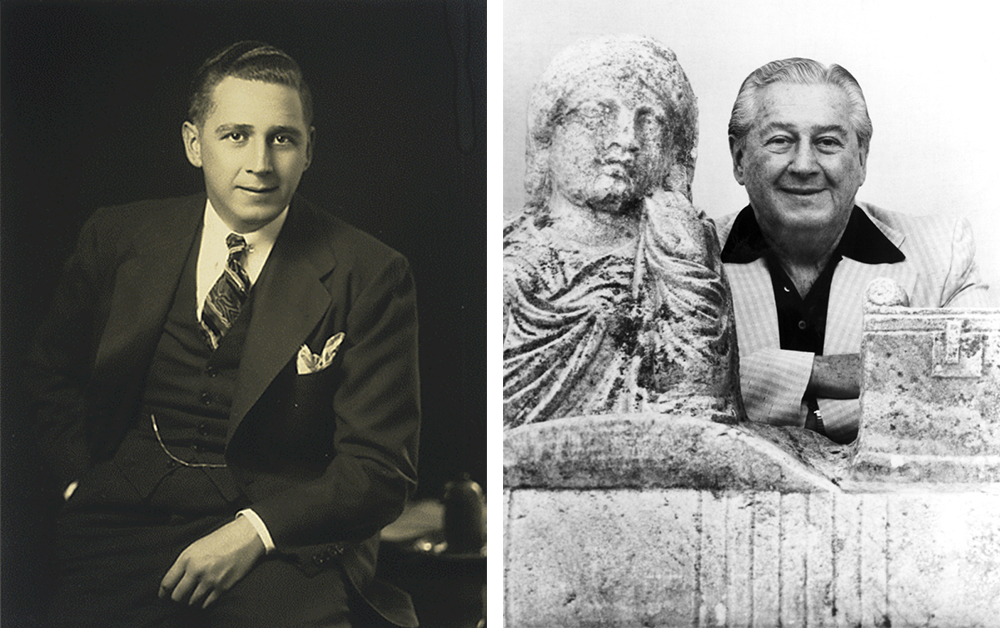

Walter P. Chrysler, Jr. (L. 1930s, R. 1980s)

The art-collecting career of Walter P. Chrysler, Jr. (1909–1988) spanned more than half a century. It began in earnest in the early 1930s with exuberant, massive buying sprees in Paris and New York. It concluded in the years just before his death, when he quietly made a small series of gifts strategically designed to “complete” the collection of his institutional namesake, the Chrysler Museum of Art. Those fifty years in Walter Chrysler’s life constitute one of the most remarkable and singular collecting arcs of the twentieth century. In fact, the indefatigable Chrysler would amass not one but two extraordinary, world-class, and altogether different collections during his lifetime. His first collection, assembled largely before World War II, focused on the artists of the contemporary School of Paris and reportedly contained hundreds of paintings by the Cubists Pablo Picasso and Georges Braque, as well as scores of works by other leading members of the French avant-garde. His second collection, built after the war, embraced a much broader and more traditional range of European and American art— everything from Italian Old Master and nineteenth-century French paintings to historic and contemporary American paintings, Art Nouveau furniture, American and European silver, and an incomparable collection of glass. He even collected antiquities. To pay for the second collection, Walter basically sold or traded the bulk of his first collection. It was that second collection that he donated to us in Norfolk between 1971 and his death seventeen years later. Given the clear before-and-after trajectory of Walter’s collecting history, we have divided the story of his collecting life into two parts. This blog covers his activities before World War II. The post-war years will be covered in the next.

Walter P. Chrysler, Jr. and his mother Della Forker Chrysler, late 1920s

The burgeoning collecting efforts of the young Walter Chrysler did not suffer from a lack of funds. His father, Walter P. Chrysler, Sr., headed one of America’s most profitable car companies, the Chrysler Corporation. Though the Chryslers’ personal fortune did not rival that of the Rockefellers or Vanderbilts, it allowed them to live very well, even lavishly, right through the Great Depression. Walter’s early collecting interests were encouraged and supported by his parents, and particularly by his mother Della, who gave him the cultural grounding expected of his class and who first introduced him to the wider world of art. She influenced her two daughters, Thelma and Bernice, in much the same way. Thelma Chrysler Foy would become a noted collector of French Impressionist paintings and decorative arts. The Museum’s splendid Renoir Daughters of Durand-Ruel once belonged to her. And Bernice Chrysler Garbisch, together with her husband Edgar William, would amass one of the first and most farsighted collections of early American folk art, a large portion of which was donated to the Chrysler Museum of Art between 1974 and 1982.

Walter P. Chrysler, Jr., ca. 1919

As a child, Walter, Jr. collected toy banks, stamps, and coins. Della and Walter, Sr. soon picked up on his collecting proclivities and challenged him with little tests, offering him “small” amounts of money and tasking him to find the best work of art he could with the funds provided. In 1923, he used $350 that his parents gave him for his fourteenth birthday (the equivalent of about $5,000 today) to buy a small painting––a watercolor depicting a landscape with a female nude by the French Impressionist artist Pierre-Auguste Renoir. It was, he later recalled, “very rich in color.” (The purchase foreshadowed Walter’s later interest in the art of the nineteenth-century French avant-garde.) After Christmas break, Walter took the watercolor back with him to the Hotchkiss School in Connecticut. There, the story goes, his straight-laced corridor master took offense to the nude and destroyed the painting. As Walter later put it, he discovered “the remains of my Renoir” in the waste paper basket outside his room “after it had been subjected to the knees and feet of our corridor master.” The episode was the first of many philistine reactions his collecting would inspire during his lifetime.

Like many anecdotes that attach themselves to the childhoods of prominent men and women, this one seems designed to make a point about an aspect of his character. Even as an adolescent, Walter the collector was a clear risk-taker; he had a strong and even fearless commitment to progressive art forms and unconventional imagery and was not afraid of raising eyebrows or vexing the status quo along the way. In February 1929, to celebrate his graduation from Hotchkiss, Della took him and Bernice on a cruise around the world. They sailed from San Francisco to Hawaii and then on to Japan, where they met with a host of Japanese dignitaries and the head of Mitsubishi Motors. They eventually passed through the Suez Canal and traveled across the Mediterranean. Walter left the tour in Italy and almost certainly continued his way through Europe, returning home in time to begin his freshman year at Dartmouth. The trip must have proved stimulating to the budding collector because right about this time, he made an even more daring art purchase: a pastel Study of a Hand by none other than Pablo Picasso. Even his parents thought this work a bit too radical, but their disapproval did not slow him down.

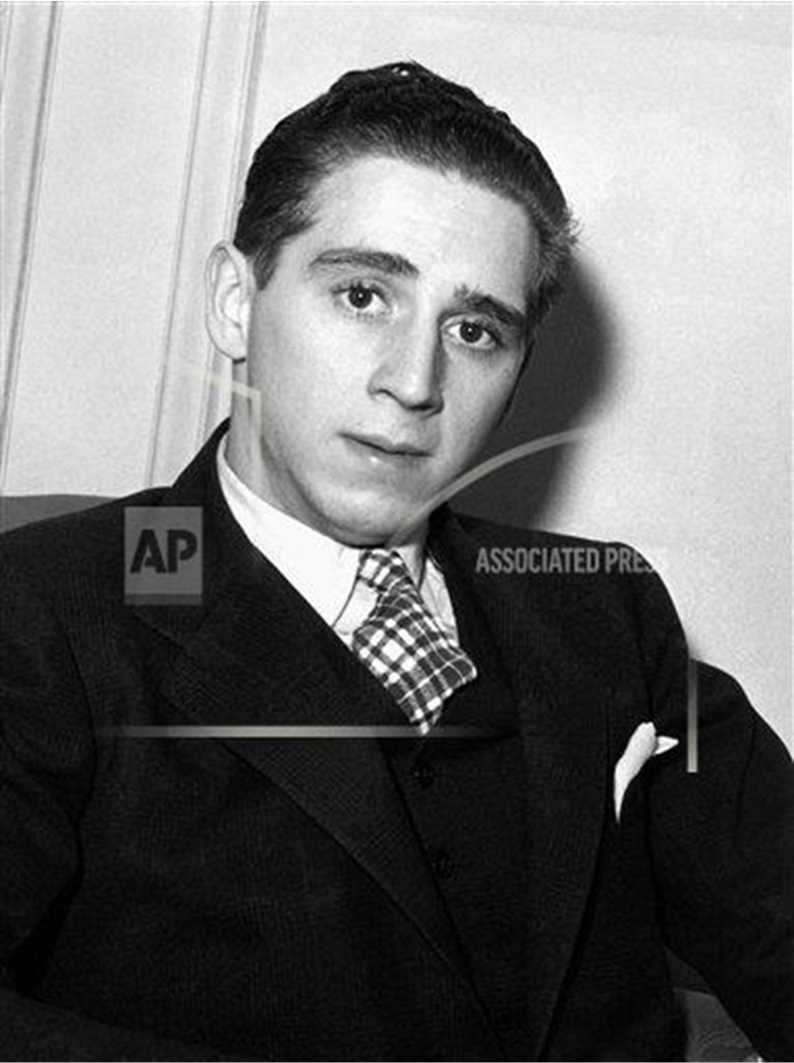

Walter P. Chrysler, Jr. ca. 1930

After two lackluster years at Dartmouth College, Walter abandoned his studies altogether and, in 1931, went to Paris. There, he met some of the greatest innovators of the European modernist movement: Picasso, Braque, Henri Matisse, Juan Gris, Fernand Léger, and the expatriate American poet and novelist who collected and fostered their revolutionary art, Gertrude Stein. The trip would prove a revelation, offering the young Chrysler, then barely twenty-two years old, his first full encounter with the intoxicating world of the European avant-garde. It launched his obsession with the modern School of Paris and began an intense decade-long buying campaign (1931–1941) focused particularly on the paintings of Pablo Picasso and his fellow Cubists. Buying both in Paris and New York, by the mid-1930s Walter had begun to amass perhaps the largest collection of Parisian modernist art in America, including major paintings by Picasso and Braque and equally important works by Matisse and other Fauve artists.

The revolutionary style of the modern School of Paris, and especially of Picasso, had been introduced to America only a few years before, in 1909, when the artist Max Weber returned from Paris to New York and began to show his Cubist-inspired paintings to near-universal condemnation. Around that time, a number of American private collectors had also begun to embrace European modernism, among them the Baltimore sisters Claribel and Etta Cone; the Philadelphia chemist Albert C. Barnes; and by the 1920s, Earl Horter in Philadelphia and Albert Eugene Gallatin in New York. The public got early glimpses of the new style at 291, the Manhattan gallery of Alfred Stieglitz, who between 1908 and 1912 mounted exhibitions of Matisse and Picasso’s art. New York’s historic Armory Show of 1913 marked the next step, introducing a much larger and often bewildered American public to over 1,400 examples of European and American modern art. In 1929, the movement gained considerably more momentum and a degree of institutional legitimacy when the Museum of Modern Art opened in a rented townhouse on West 53rd Street in Manhattan. The museum was dedicated specifically to the collecting and display of European and especially French modern art, and it served to nurture an ever-growing contingent of young American private collectors. Yet, despite their growing acceptance among America’s cultural elite, works by Picasso and company were still daring purchases for someone like Walter Chrysler in the early 1930s when the general public and popular press remained deeply hostile to these “dangerous” new art forms.

Nelson Rockefeller, ca. 1930s

Other than general comments about his mother’s support of his early interest in art, Walter offered few clues about who might have inspired his turn toward modernism. But we do know of one prominent New Yorker who may have encouraged Walter early on in that direction: Nelson Rockefeller. Walter met Nelson in 1929 when the two were students at Dartmouth. Walter was immediately attracted to the wealthy Rockefeller scion and soon attempted to emulate and even rival him as an art connoisseur and collector. The two collaborated on a campus art and literary magazine, The Five Arts, and Walter quickly went on to found his own publishing company, Cheshire House, which produced a number of luxury volumes for well-heeled bibliophiles. Like many of his early art projects, it was riddled with debt and short-lived.

Walter and Nelson continued to cross paths during the 1930s. By then, Nelson had emerged as an important modernist collector and one of the principal American advocates of the new style. His mother, Abby Aldrich Rockefeller, had just co-founded the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA), and with her backing, he became MoMA’s first president in 1939. Walter, too, became active at MoMA early on. He was named the first chairman of the museum’s library committee and worked to expand the library’s collection.

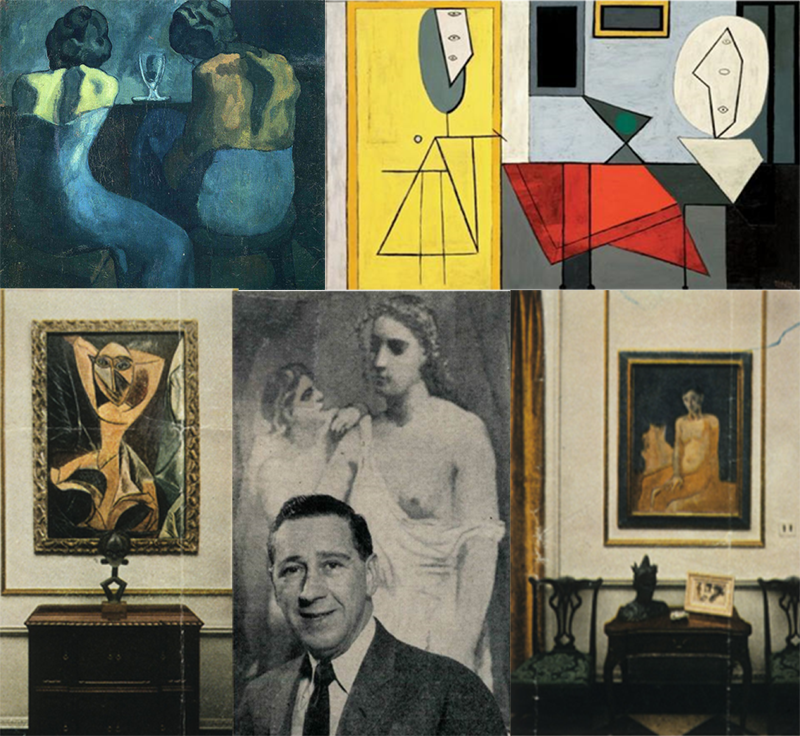

Pablo Picasso, The Studio, Paris, winter 1927-28, Oil on canvas, Gift of Walter P. Chrysler, Jr., © 2021 Estate of Pablo Picasso / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York, 213.1935

In 1936, he donated the Paul Éluard-Camille Dausse collection of surrealist materials to the library, and in 1935, he gifted to the museum one of Picasso’s most famous paintings of the late 1920s, The Studio. During the 1930s and ‘40s, he regularly lent to shows at MoMA, including thirty-two Picassos to the museum’s 1939 exhibition, Picasso, 40 Years of his Art. The exhibition press release described his Picasso holdings as the largest in America. Eager to advertise his collection and himself more broadly, Walter also began to send his art on the road, something he would often do in the 1950s and ‘60s. In 1937, he exhibited part of his collection—some forty-five works—at the Detroit Institute of Arts and the Arts Club of Chicago.

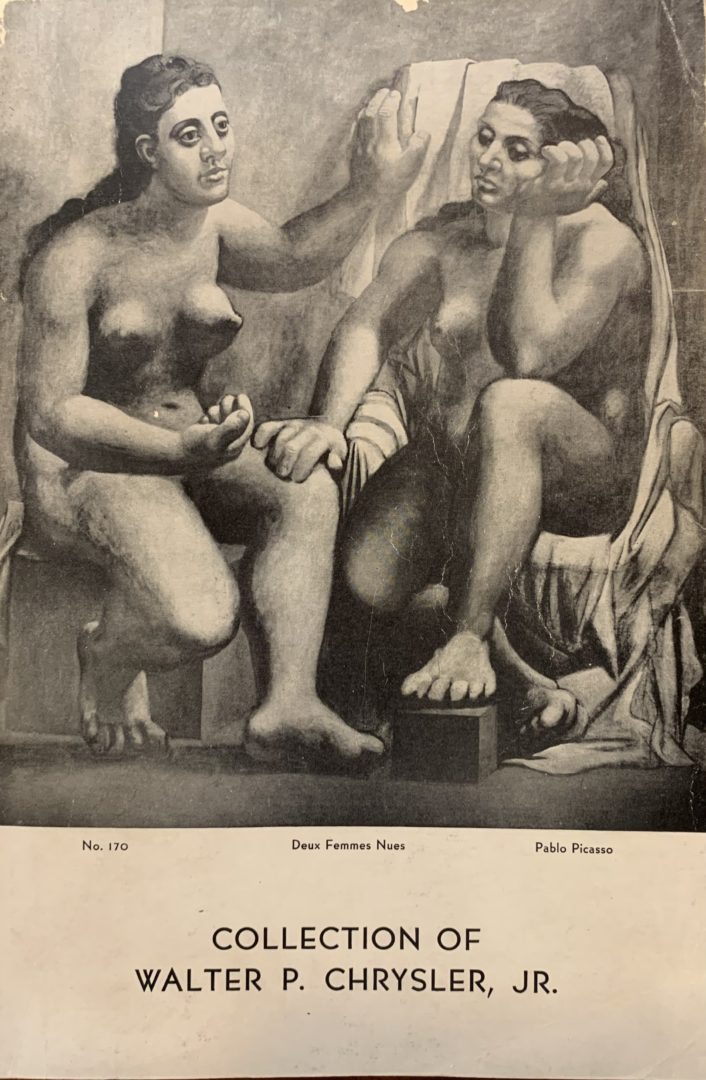

Collection of Walter P. Chrysler, Jr., Exhibition catalogue cover, 1941

In 1941, he showed a much broader swath of his modernist works, along with a selection of Old Masters and American folk paintings, in a show that traveled to the Virginia Museum of Fine Arts in Richmond and the Philadelphia Museum of Art. The show featured eighty-nine works by Picasso alone, and as one might have expected, the response from some of the more provincial critics was predictably dismissive. One Richmond newspaper reporter wrote that the exhibition contained “a few things to admire, a lot to hate, and much to laugh out loud over.”

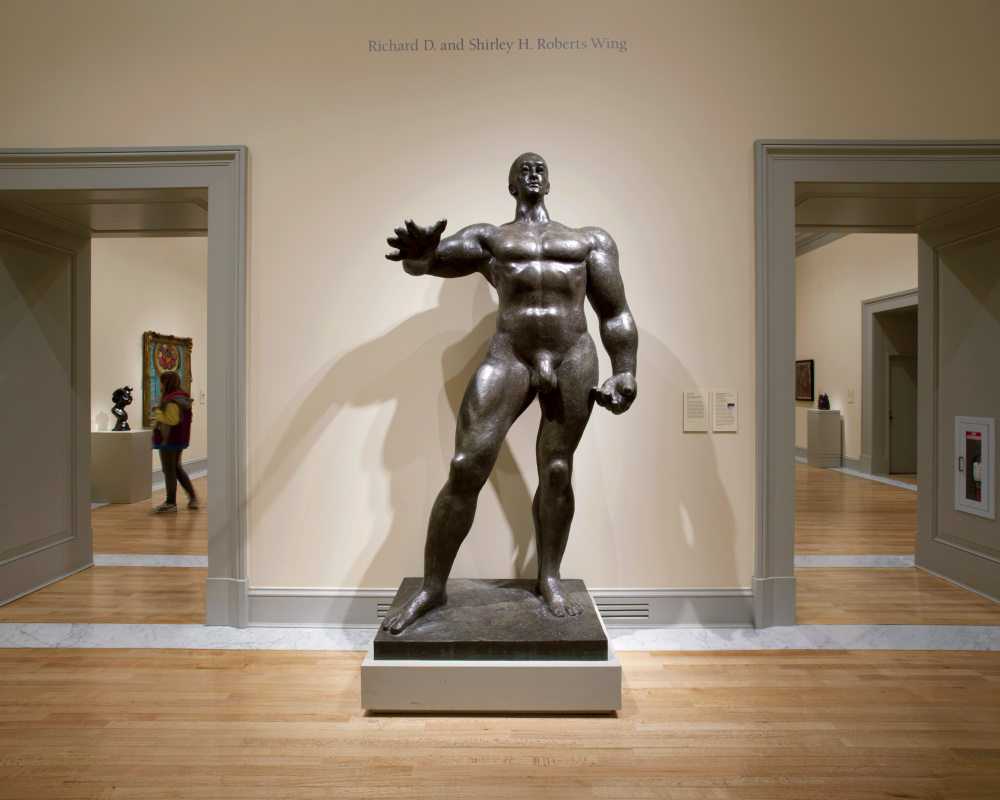

Gaston Lachaise’s Man, Gallery 221, 20th Century American Art

It was inevitable that Walter and Nelson’s collecting efforts would occasionally overlap and even dovetail. Such was the case in 1939 when Walter commissioned the first bronze cast of Gaston Lachaise’s colossal sculpture Man. Soon after, Nelson ordered his own cast and had it installed on the grounds at Kykuit, the Rockefeller family estate near Tarrytown, New York. Walter followed suit, installing his cast at the entrance to the Chrysler estate at King’s Point on Long Island.

Walter P. Chrysler, Jr. and first wife Peggy Sykes Chrysler

Walter’s bold proclamation of his modernist bona fides was soon scuttled by his wife at the time, Marguerite (Peggy) Sykes Chrysler. She hated the sculpture. “Everything on the Man was double the size it should be,” she later said, and she quickly ordered it removed. It is on display today in the American wing of the Chrysler Museum of Art. (Peggy Sykes would divorce Walter in late 1939. Despite her somewhat retrograde artistic tastes, she would become a feminist pioneer. In 1948, she graduated from the New York University School of Medicine, which was only the second class there to admit women. She went on to a distinguished forty-year career in chemotherapy at Memorial Sloan Kettering Hospital in Manhattan. She died in 2012 at age ninety-eight.)

Walter P. Chrysler, Jr. at North Wales

Rockefeller and Chrysler crossed paths at least one more time before World War II. In 1940, President Franklin Roosevelt appointed Rockefeller to lead the newly formed Office of the Coordinator of Inter-American Affairs, whose mission was to guarantee American access to raw materials from Latin America as war approached. Chrysler soon joined the Office, almost certainly at Rockefeller’s invitation. About that time, Chrysler bought North Wales, a mammoth estate and horse farm in Northern Virginia, in part perhaps to be close to his new job in Washington, D.C. It is unclear if Chrysler was officially vetted for the position. In any case, in a matter of months, he applied for another government job, this one in the Office of Production Management. This time he was indeed formally vetted by the FBI and rejected when the findings proved too negative. (Many of those interviewed voiced rumors of his homosexuality, which immediately disqualified him for government service). Soon after, and almost certainly with the Chrysler family’s help, Walter joined the Navy as a lieutenant junior grade.

Walter P. Chrysler, Jr. with a composite of Picasso paintings he owned over the years.

By 1940, Walter’s collection was touted as the largest private holding of French modernist art in America. His Picasso collection, in particular, was described in equally glowing terms as unrivaled in scope and quality. Indeed, in later years, Walter claimed to have owned 347 Picasso paintings, sculptures, and works on paper. Though not impossible, that astonishing claim has never been confirmed and could have been floated by him largely for dramatic effect. Over the course of his life, Chrysler was prone to exaggerate the size of his art holdings and the scope of his collecting career. In later years, for example, he claimed that at one time he owned more than 800 European paintings and that 25,000 works of art had passed through his hands.

Furthermore, in the 1930s, it was difficult to determine precisely what art Chrysler owned and when he owned it. (It sometimes still is.) He was, by nature, a secretive man who took pains to shroud his personal life and obscure his collecting tracks. He eschewed detailed record-keeping, preferring to keep his collecting activities and methods close to his chest. He moved quickly, buying and selling art at an often feverish pace and leaving little in the way of a paper trail along the way. He generally avoided acquisition through public auction, preferring to buy privately either directly from an artist’s studio or a commercial art gallery. (In New York, he regularly bought in the 1930s from the Valentine, Weyhe, Pierre Matisse, and Marie Harriman galleries. He was known as a ferocious bargainer.) He further muddied the waters in 1932 when he opened his own commercial art gallery, the Cheshire, on the ground floor of the Chrysler Building and began to resell some of the art he had just bought. Over time, he would rely more and more on acquisition through trade, making his transactions even harder to trace or document.

Walter was an aggressive, even ruthless, competitor who used subterfuge and sleight of hand to outsmart his collecting rivals. He even claimed to have outfoxed Gertrude Stein. During one of his Paris visits, he and Stein each agreed to donate one of their Picasso paintings to help build the inventory of a struggling art dealer. Walter convinced Stein to give up her prized Blue Period Picasso, his Two Women at a Bar from 1902. Once the painting was deposited with the dealer, Chrysler quietly visited him and purchased the work himself for a mere $450. (A rogue is a rogue is a rogue, yes?) He later said he traded it after World War II for $1,600,000 worth of pictures. The painting belongs today to the Hiroshima Museum of Art in Japan. Walter’s subterfuge even determined his wardrobe choices. As Marguerite Sykes reported, to avoid looking like rich Americans, he made sure they “dressed poor” before beginning a day of art shopping in late 1930s Paris.

Given all this, much of Walter’s modernist collection remained chronically under-documented during the 1930s. Yet, there are enough reliable sources today in the form of archives, indexes, monographs, and exhibition and collection catalogs to confirm that his Picasso collection and other modernist holdings were indeed extraordinary and probably unrivaled in both their size and stylistic range. Among the scores of masterpieces he owned and ultimately traded were Picasso’s Bust of a Man (Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York), Picasso’s Charnel House and Matisse’s Dance (both today in the Museum of Modern Art, New York), Braque’s Artist and Model (Norton Simon Museum, Pasadena), and his Port in Normandy (Art Institute of Chicago). One could go on and on.

Walter’s modernist collection reached its fullest form just before World War II, when the transatlantic art trade came to a virtual halt. The post-war years in America would be marked by entirely new collecting strategies and opportunities, and the irrepressible Chrysler would take full advantage of them. Playing, as it were, at a totally different game board and with a completely new set of opponents, he would sustain his reputation as one of the cagiest, most daring, and farsighted art collectors in America. Stay tuned for Part II.

**For a full account of Walter P. Chrysler, Jr.’s life and collecting career, see particularly Peggy Earle’s excellent Legacy: Walter Chrysler Jr., and The Untold Story of Norfolk’s Chrysler Museum of Art, University of Virginia Press, Charlottesville and London, 2008; Jefferson C. Harrison et al., Collecting with Vision: Treasures from the Chrysler Museum of Art, D. Giles Limited, London, 2007; and Vincent Curcio, Chrysler: The Life and Times of an Automotive Genius, Oxford University Press, Oxford and New York, 2000.