- Open today, 10 am to 5 pm.

- Parking & Directions

- Free Admission

The Myers Table: Dining in the 18th Century

–Karen Dutton, Assistant Visitor Services Manager

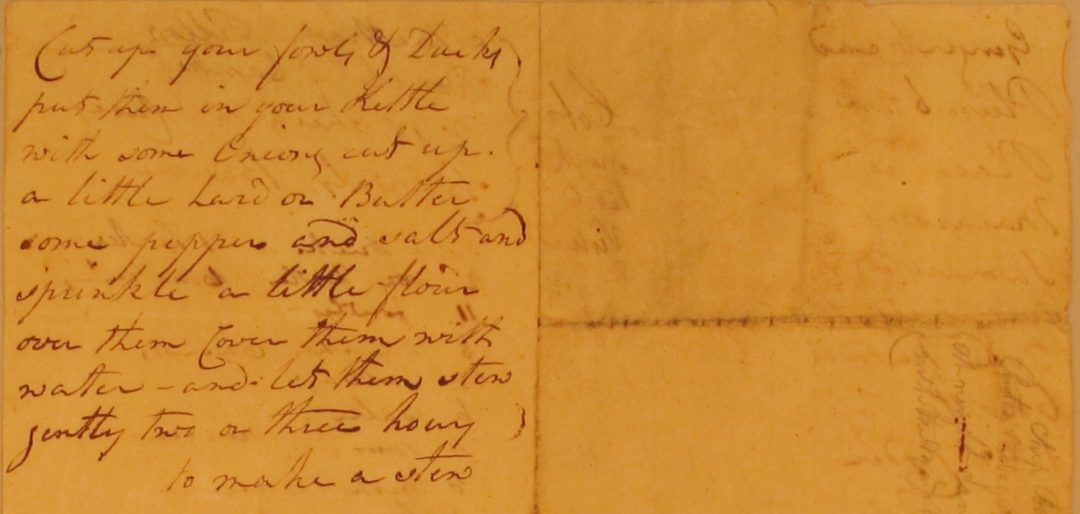

As the holiday season approaches, many home chefs are digging into their family records in search of time-honored recipes and traditional dishes. At the Moses Myers House, our Gallery Hosts are studying the recipes, letters, and ledgers of the Myers family in hopes of gaining insight into their daily lives and in turn, getting a broader sense of what life was like in Norfolk over 200 years ago.

Moses and Eliza Myers moved to Norfolk in 1787. They were the first permanent Jewish residents of the borough. The stunning architecture and opulent furnishings of their home offer a glimpse into the life of a wealthy maritime merchant. Through Moses’s handwritten ledgers, we learn what food cost and can look for correlations between price fluctuations and historic events.

We clearly see that the food available in Norfolk’s Market Square was almost entirely local and seasonal. During the spring and summer months, the Myers enjoyed mutton, veal, tomatoes, peas, cucumbers, asparagus (a favorite vegetable in the family, as Moses bought it several times a week when it could be had), peaches, and strawberries. Watermelons and muskmelons were sometimes made into preserves. They bought fish, geese, wild ducks, turkeys, chickens, sweet potatoes, cabbage, turnips, and apples in the fall and winter. The Myers archives also contain more than one recipe for medicines to treat the various stomach ailments which might arise from over-indulging at dinner.

Moses Myers would have been familiar with the practice of keeping a kosher diet from childhood. His father, Hyam Myers, filled the position of shochet for Shearith Israel in New York, meaning he prepared the kosher meat in strict accordance with Jewish dietary laws for their local Jewish community. During his time in Norfolk, however, Moses Myers did not keep a kosher diet. His food ledger includes non-kosher items such as ham, oysters, crab, and on very special occasions the family ate turtle, as we see in this letter from Moses to his eldest son, John, in November of 1810:

“I had kept the best turtle to toast your friends. . . The weather getting too cold for it I was obliged to kill it & having asked a large company to dine with Southgate & family tomorrow had the turtle sent up to the house this afternoon to be dressed . . . So we shall have a full table & will drink your health.”

The Myers family’s men did the daily marketing (the 18th century run to the store), while the ladies directed the menu for parties and special occasions. Some of the Myers recipes are time-consuming and complex. Their recipe for “light bread or rolls” took three days to prepare.

Moses Myers House, Kitchen, 2018

Though the Myers women knew how to cook, this laborious task was carried out by people who were enslaved. The value of the work done by the enslaved cook cannot be overstated. They were responsible for every meal, for not only the Myers family and their guests, but also all of the enslaved people who lived in the Myers house. The work was physically demanding, difficult, and at times dangerous. All meals were prepared on or near an open hearth, the water used for the house was, of course, untreated, and in the days before refrigeration handling raw meat would expose one to disease.

We do not know the name or identity of the cook who was enslaved at the Myers house, but research is ongoing. References to the Myers enslaved cook can be found in the recently opened exhibition at the Myers house that highlights the contributions of people who were enslaved.

Moses Myers House Dining Room, 2010

For the Myers the most important meal of the day was dinner, which was eaten in the late afternoon. One of the earliest accounts of a dinner at the Myers house comes from writer Moreau de Saint Mery in 1794:

“Business connections lead us to the home of Mr. Myers. . . Everyone speaks of his obliging nature. . . As it was almost half-past one when we debarked, we were going to see about having dinner, when Mr. Myers kind invitation was extended to all . . .The sumptuously laden table on which we gazed reminded us of a wedding feast. Not only the simple and warm welcome, but everything we saw proved a delight – the food, a good mother who even suckled her husky baby during the meal, and four fine children.”

While gatherings may look as different this year as they did in the 18th century, we wish you a safe holiday season.

To learn more about foodways and other aspects of life in early Norfolk, visit the Moses Myers House, Saturdays and Sundays from noon to five. Capacity is reduced to 12 guests at a time and all visitors are required to wear a face covering.

The Myers Archive is available to researchers at the Jean Outland Chrysler Library and a selection of collection objects can be viewed here.