- Open today, noon to 5 pm.

- Parking & Directions

- Free Admission

The History of Art in Colors

White – The Technology of Paint

White is one of the most ubiquitous colors in paintings. Art stores with rows of white canvases and endless tubes of white paint have perhaps primed us to pass by this humble “color” without much thought. However, in the absence of color, white paint reveals something often not discussed: the technology of paint itself. From the Old Master oil paintings of Europe and the experimental works of Picasso to the birth of modern acrylic paints, white pigments have played a critical role in not only coloring paint but also formulating a paint that handles well and can stand the tests of time.

Base Lead – Golden Properties

White’s story begins with base lead. While many apocryphal tales of alchemy suggest that gold is the ultimate end product of this element, lead white has certainly found a far more important, albeit less mystical, place in the history of world. From the advent of oil painting in Europe until the nineteenth century, lead white was the premier white pigment for artists. Metallic lead is dark grey to begin with. In a reaction similar to the rusting of iron, simple white vinegar can be used to spur the corrosion of metallic lead, producing a powdery mixture of basic lead carbonate and lead hydroxide known more simply as lead white. When mixed with a drying oil such as linseed, the resulting paint possessed somewhat mythical but real qualities. When cured, the paint film is remarkably permanent and tough, often the reason why the lightest parts of an Old Master painting remain the best preserved after centuries of wear and tear. Lead white paint also had many immediate benefits, including accelerating the drying of slow oil paints, and most famously, providing an incredibly heavy-bodied oil paint that imparted texture to brush strokes.[1]

Bernardo Strozzi is an excellent example of a painter that exploited the unique textural opportunities of lead white. As seen in The Martyrdom of Saint Justina (ca. 1635), the white cuffs of Saint Justina appear to be piled onto the surface of the painting, adding depth and drama. Because of its permeance and gelled consistency, lead white remained largely unchanged and ubiquitously used into the twentieth century.[2] Even in the nineteenth century, when other white pigments became available for the first time, painters still treasured the hazardous lead pigment for creating texture, as seen in the work of Academic painters like Gustave Doré. His work The Neophyte (ca. 1866–1868) is nearly colorless but livened by a substantial surface texture—the bravado brushwork of a master painter using thick lead white paint.

Bernardo Strozzi (Italian, 1581–1644), The Martyrdom of Saint Justina, ca.1635, Oil on

canvas, Gift of Walter P. Chrysler, Jr., 71.526

Gustave Doré (French, 1832–1883), The Neophyte (First Experience of the Monastery), ca. 1866–1868, Oil on canvas, Gift of Walter P. Chrysler, Jr. © Chrysler Museum of Art, 71.2061

The Chemistry of Texture

Many painters may struggle to understand the unique and once treasured textural properties of lead white because most tubes of oil paint now come unnaturally standardized. Nearly every tube contains buttery-smooth oil paint of uniform consistency that can be loaded onto a brush with impasto or thinned to a desired fluidity, but we must realize that this is the product of modern chemistry; it is an intentional mimicking of textures produced by pigments like lead white.

Tubes of oil paint squeezed out. By Marco Verch. CC 2.0

When lead white is mixed with oil, it reacts with the acidic oil components to form a new compound called metal soap. These compounds thicken and stabilize the paint to form the characteristic buttery, gelled texture. When this chemistry was decoded in the early twentieth century, paint manufacturers simply began adding isolated metal soaps to oil paints that did not produce their own, thus giving the richly uniform buttery consistency to all colors. In conjunction with additions of waxy compounds such as hydrogenated castor oil and/or inert particles such as alumina hydrates, the typically liquid colors like lake red that formerly could only be applied in thin, fluid layers became the thickly bodied oil paints to which we are now accustomed.[3] Additionally, these newly formulated paints allowed tubes of artists’ oil color to remain on the shelf without separating, fostering their large-scale commercialization.[4] This early-twentieth-century technology proved critical for maintaining the gelled texture of white paint as lead white was phased out in favor of the now-ubiquitous titanium white.

Titanium White: The Triumph of Chemistry

Titanium dioxide white has become the premier white pigment for nearly every application—from skincare to food and, in our story, paints. When browsing a selection of white oil, acrylic, alkyd, or watercolor paints, titanium dioxide will be the pigment listed on the label. It came to dominate the world due to its high covering ability; very bright white color; and, most importantly, its non-toxic formulation that replaced lead. This deceptively simple pigment is, in fact, the product of decades of twentieth-century chemical-industrial research, and its story is critical to the development of modern-contemporary art.

Titanium dioxide white is synthetic pigment. Ores that contain titanium are mined and must be heavily processed to produce the brilliant white pigment. Early twentieth-century attempts failed to remove iron oxide residues in the raw ores, instead producing titanium buff colors that also enjoy some popularity today. In fact, the history of improving upon this difficult process reaches as recently as the 1980s when standardized universal grades were developed. Unlike many historical pigments, titanium dioxide is a complicated lamination of materials that form a finished product. Much like a piece of plated jewelry, the pigment is made starting with a base core—in this case, barium or calcium sulfate (inert white particles)—onto which is coated the extracted titanium dioxide.[5] Advances in the industrial-chemical technology in the 1950s further allowed for these particles to be sealed with nano-thin layers of glass-like, colorless silica that ensured the final titanium pigment was also completely non-reactive and thus completely stable.[6] It is this stability that has ultimately allowed titanium dioxide white to proliferate so widely as pigment in artists’ materials. Earlier uncoated particles caused rapid deterioration of paints.

Fluidity: New Innovations

In the past, choosing the right white pigment for the binder employed was critical. Lead white is very stable in oil but turns black if used as watercolor. Zinc white was the most popular white for watercolor, but it forms a very brittle, problematic film of oil paint. [7] Coated titanium white offered a new universal solution; its brilliant white color is chemically inert and stable in all mediums. After decades of industrial tinkering to create a stable and brilliant new white pigment, the wide-reaching implications of such a product were realized—most importantly for the invention of water-based acrylic paint. Since white pigments like lead and zinc white cannot form a stable acrylic paint, the development of silica-coated titanium white in the 1950s was fundamental to the creation of modern acrylic emulsion paints.[8] The medium was quickly picked up by artists looking to explore new possibilities. Artists like Frank Stella used this new medium to paint flat and solid fields of color—not to create illusions of form nor to texture their surfaces. Acrylic paints offered a fluidity that was novel, the opposite of the gelled artist’s oil paint typified by lead white. This fluidity was thanks to the modern technology of titanium white.

Frank Stella (American, b. 1936), Manteneia II, Acrylic on canvas, Gift of Walter P. Chrysler, Jr. © Frank Stella / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

The desire for fluid paint was not without precedent before the experiments of the mid-twentieth century modernists. Picasso widely used non-traditional artists’ materials like fluid house paints to achieve flat, modern surfaces as seen in Composition for Bal de la Mer (1928). Again, white pigments have a role in this story. Zinc oxide white is said to have transformed early ready-made commercial house paint. Due to its unique chemistry, the white pigment can form a very shelf-stable can of fluid, oil-based paint. The advent of this modern pigment in the nineteenth century allowed for the commercial availability of early-twentieth-century house paints like the famous Ripolin.[9] [10] If not the art world, white house paint certainly took the rest of the world by storm. In 1925, the architect Le Corbusier commanded, “Every citizen is to replace his hangings, his damasks, his wallpapers, his stencils with a plain coat of white Ripolin.”[11] In the 1930s, companies like DuPont Chemicals marketed products like Dulux Super White, interior house paint with the new brilliant titanium white pigment.[12]

Pablo Picasso (Spanish, 1881–1973), Composition for Bal de la Mer, 1928, Oil on canvas, Gift of Walter P. Chrysler, © Estate of Pablo Picasso / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York, 71.689

Titanium White Paint: A Continuing Legacy

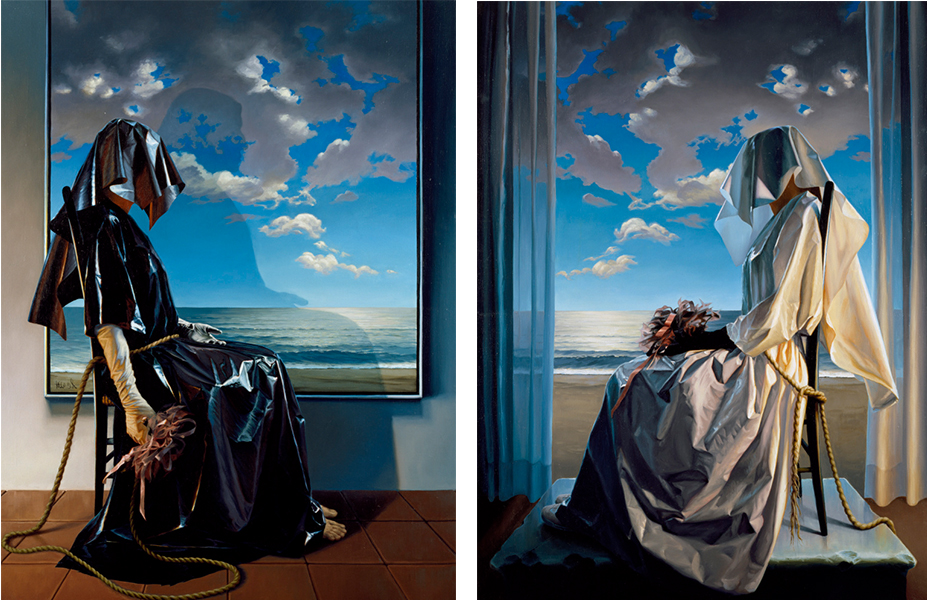

Although titanium white became a symbol of the Modernist’s materials, it eventually replaced the lead white pigments in traditional artists’ oil paints due to the overwhelming health concerns of working with lead. This also offered traditional painters new range of color. As seen in more painterly works like Sarai (1981) and Hagar (1981) by Nancy Camden Witt, titanium white offers a brilliant and cool shade of white not available to artists in previous centuries.

(Left) Nancy Camden Witt (American, 1930–2009), Hagar, 1981, Oil on canvas, Gift of the family of Joel B. Cooper, in memory of Mary and Dudley Cooper, © Nancy Camden Witt, 2002.26.11

(Right) Nancy Camden Witt (American, 1930–2009), Sarai, 1981, Oil on canvas, Gift of the family of Joel B. Cooper, in memory of Mary and Dudley Cooper, © Nancy Camden Witt, 2002.26.12

Art stores now stock a nearly endless range of white paints that encompass a variety of properties, including opacity, tinting strength, texture, and drying rate. All these paints are largely made from titanium oxide white and sometimes zinc oxide. In the absence of color and pigment diversity, these paints illustrate the incredible range of modern paint formulation. While artists like Stuart Semple are distracting us with brilliant shades of new color such as the pinkest pink, white will always remain at the heart of paint technology, for its timeless ubiquity demands it.

Stay tuned for another article on the curious history of color in art. Next week I’ll be discussing green – the problematic and poisonous pigments.

–Brandon Finney, NEH Conservation Fellow

[1] Rutherford J Gettens, Hermann Kühn, and W T Chase, ‘Lead White’, in Artists’ Pigments: A Handbook of Their History and Characteristics. Volume 2 (Washington DC: National Gallery of Art, 1993).

[2] Gettens, Kühn, and Chase.

[3] Francesca Caterina Izzo, ‘20th Century Artists’ Oil Paints : A Chemical-Physical Survey’, ed. by Guido Biscontin (Venice: Università Ca’ Foscari Venezia, 2011).

[4] Charles S Tumosa, ‘A Brief History of Aluminum Stearate as a Component of Paint’, Newsletter (Western Association for Art Conservation), 23.3 (2001).

[5] Marilyn Laver, ‘Titanium Dioxide Whites’, in Artists’ Pigments: A Handbook of Their History and Characteristics. Volume 3 (Washington DC: National Gallery of Art, 1997).

[6] Stuart Croll, ‘Overview of Developments in the Paint Industry since 1930’, in Modern Paints Uncovered: Proceedings from the Modern Paints Uncovered Symposium (Los Angeles: Getty Conservation Institute, 2007).

[7] Hermann Kühn, ‘Zinc White’, in Artists’ Pigments: A Handbook of Their History and Characteristics (Washington DC: National Gallery of Art, 1986).

[8] Laver.

[9] Gillian Osmond, ‘Zinc White : A Review of Zinc Oxide Pigment Properties and Implications for Stability in Oil-Based Paintings ’, AICCM Bulletin , 2012, 20–29 <https://doi.org/10.1179/bac.2012.33.1.004>.

[10] Croll.

[11] L Corbusier, The Decorative Art of Today (MIT Press, 1987) <https://books.google.ca/books?id=1YFQAAAAMAAJ>.

[12] Harriet Standeven, ‘“Cover the Earth”: A History of the Manufacture of Household Gloss Paints in Britain and the United States from the 1920s to the 1950s’, in Modern Paints Uncovered: Proceedings from the Modern Paints Uncovered Symposium (Los Angeles: Getty Conservation Institute, 2007).

Bibliography

Corbusier, L, The Decorative Art of Today (MIT Press, 1987) <https://books.google.ca/books?id=1YFQAAAAMAAJ>

Croll, Stuart, ‘Overview of Developments in the Paint Industry since 1930’, in Modern Paints Uncovered: Proceedings from the Modern Paints Uncovered Symposium (Los Angeles: Getty Conservation Institute, 2007)

Gettens, Rutherford J, Hermann Kühn, and W T Chase, ‘Lead White’, in Artists’ Pigments: A Handbook of Their History and Characteristics. Volume 2 (Washington DC: National Gallery of Art, 1993)

Izzo, Francesca Caterina, ‘20th Century Artists’ Oil Paints : A Chemical-Physical Survey’, ed. by Guido Biscontin (Venice: Università Ca’ Foscari Venezia, 2011)

Kühn, Hermann, ‘Zinc White’, in Artists’ Pigments: A Handbook of Their History and Characteristics (Washington DC: National Gallery of Art, 1986)

Laver, Marilyn, ‘Titanium Dioxide Whites’, in Artists’ Pigments: A Handbook of Their History and Characteristics. Volume 3 (Washington DC: National Gallery of Art, 1997)

Osmond, Gillian, ‘Zinc White : A Review of Zinc Oxide Pigment Properties and Implications for Stability in Oil-Based Paintings ’, AICCM Bulletin , 2012, 20–29 <https://doi.org/10.1179/bac.2012.33.1.004>

Standeven, Harriet, ‘“Cover the Earth”: A History of the Manufacture of Household Gloss Paints in Britain and the United States from the 1920s to the 1950s’, in Modern Paints Uncovered: Proceedings from the Modern Paints Uncovered Symposium (Los Angeles: Getty Conservation Institute, 2007)

Tumosa, Charles S, ‘A Brief History of Aluminum Stearate as a Component of Paint’, Newsletter (Western Association for Art Conservation), 23.3 (2001)