- Open today, 10 am to 5 pm.

- Parking & Directions

- Free Admission

The History of Art in Colors

Red–A Color to Dye For

The nineteenth century saw a curious fashion trend: the elaboration of gowns with colorful green beetle elytra. As seen in the famous painting of Ellen Terry as Lady Macbeth, the brilliant casings of the Indian Jewel Beetle added sparkle and mystique to the otherwise familiar Medieval robes of the Scottish Queen.

Ellen Terry as Lady Macbeth 1889 John Singer Sargent 1856-1925 Presented by Sir Joseph Duveen 1906 http://www.tate.org.uk/art/work/N02053

Dress with Indian Jewel Beetles. 1868–9. Maker unknown, British. Given by Kathy Brown T.1698:1 to 5-2017 © Victoria and Albert Museum, London.

Although we may think this a rather strange choice of decoration, the use of insects for fashion dates back to the Neolithic period 12,000 years ago. [i] The scale insects kermes and cochineal have been used to produce red colorants for centuries in the Western world.

Kermes. By Spodek M, Ben-Dov Y – Spodek M, Ben-Dov Y (2012). CC BY 3.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=23230060

Female cochineal (Dactylopius coccus) in Barlovento, La Palma, Canary Islands. By Frank Vincentz – Own work, CC BY-SA 3.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=3710466

These strange looking clusters have beguiled biologists for just as long as the common person. While most insects scuttle or fly, the female scale insect instead remains stationary their entire life, solely feeding on their host plant through a permanently attached straw-like mouth. The kermes is found across Europe on oak trees and other plants while the cochineal lives on cacti in Mexico, South America, and the southern United States. [ii] Perhaps many of us may not be interested in insects—let alone these unappealing parasites—but these little creatures contain a wealth of history: from luxury fashions and violent trade wars to widespread piracy and of course, color—particularly the search for a red brilliant enough to dye for.

Carmine Powder, By Stephhzz – CC BY-SA 3.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=67523649

While these scale insects appear incredibly dull at first, when boiled they release a colorful red acid collectively known as carmine or red lake (owing to its water origins). Kermes insects are the source of the most ancient red dyes known in the Western world; they were produced in the Old World since before Antiquity. Cochineal was only imported to Europe in 1523 following the Spanish conquests of Meso-America.[iii] The colors were tremendously popular in textile dying. As seen across works from the Chrysler collection spanning centuries, red has always been the color of status, style, and fashion. We see the Madonna, successful Florentine merchants, and French aristocrats all robed in red. Modern celebrities still walk down the red carpet, a symbol of their elevated social status.

Naddo Ceccarellicirca (Italian, active ca. 1339–1347), Madonna and Child Flanked by Four Saints, ca. 1339-1347, Tempera and gold leaf on panel, Gift of the Irene Leache Memorial Foundation, in recognition of the leadership and guidance of its Presidents, 1901–2014: Annie Cogswell Wood, Fannie Rogers Curd, Melissa Payne King, Nannie Baylor Wolcott, Frances Ferguson Carney, Juliet McClure Dalton, Indiana Lindsay Bilisoly, Clara Mitchell Wolcott, Edith Brooke Robertson, Carter Grandy Bernert, Gail Kirby Evett, Jo Ann Mervis Hofheimer, Harriet Travilla Reynolds, Vickie Bowdoin Bilisoly, 2014.3.5

Master of the Castello Nativity, (Italian, Florence, ca. 1445 – 1475) Portrait of Michele Olivieri, ca. 1450, Tempera on panel, Gift of Walter P. Chrysler, Jr., 83.584

Gioacchino Giuseppe Serangelica (Italian, 1768–1852), Portrait of Germaine Faipoult de Maisoncelle and Her Daughter Julie Playing the Spinet, ca. 1799, Oil on canvas, Purchase and Gift of Walter P. Chrysler, Jr., Walter Beineke, Jr., Mr. Edward J. Brickhouse, Mr. Morrie A. Moss, Mr. and Mrs. Hugh Gordon Miller, Mr. Per Madsen, and Mr. and Mrs. Eugene Garbaty, by exchange, 2005.11

Seeing Red: Status and Skirmish

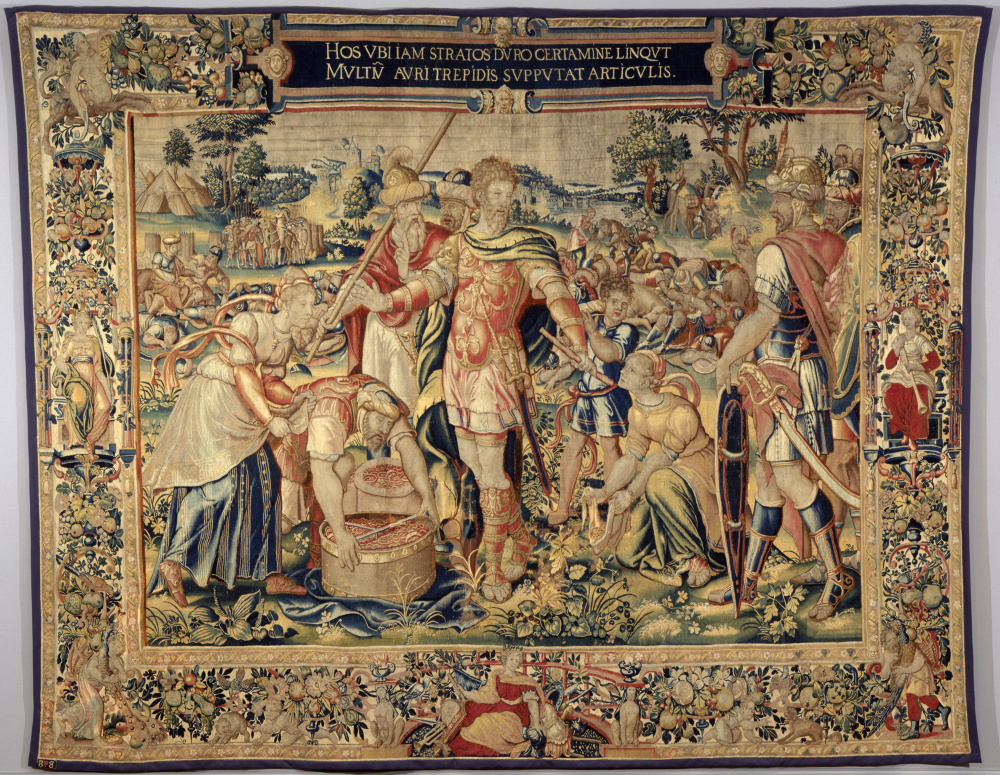

Red became a status symbol because, in addition to its desirable appearance, extracting enough colorant from the European kermes insect to create a dye for cloth was tremendously expensive. As such, nearly all the carmine ever extracted was reserved for luxury fabrics like silk, itself an incredibly costly import from the East. The silk was made into clothes and other luxury items like tapestries, long held as the costliest objects to ever be produced. The vibrant, deep red silk threads of our tapestry The History of Hannibal: The Spoils of Cannae are certainly dyed with one of the carmine colors. More accessible woolen garments were colored with a much more economical red dye from the common madder plant that produced a greater amount of dye in a much duller orange-red color.[iv]

Attributed to François Geubels (Flemish, active 1546–1579), The History of Hannibal: The Spoils of Cannae, ca. 1550, Wool and silk tapestry, Gift of the Irene Leache Memorial Foundation, in memory of Anna Cogswell Wood, 2014.3.17

Just as Hannibal returned with the spoils of Cannae, the Spanish Conquistadors returned from Mexico in 1523 with precious cargo—cochineal carmine red. It wasn’t Aztec gold, but it was nearly as precious[v] The Meso-American cochineal produced a higher quality red dye than kermes. It was said to have a dying strength that was ten times that of European kermes. The Chrysler holds an antique Peruvian textile that depicts cats and showcases the deep red the dye could achieve. The Spanish luxury cloth industry blossomed with the use of this new discovery, keeping most of the dye exclusively in Spain until 1550. Even after it became available for export across Europe, the Spanish held an airtight monopoly on the production of the new and much-desired shade of red. The Spanish controlled the source of the color, the ports of the New World in Mexico, but also held the secret to what exactly the color was. Even as late as 1599, Samuel de Champlain described the New World cochineal as a plant that could be replanted from seeds akin to a pea. [vi]

Fragment With Curled-Tail Cats, 1100–1460, Wool, cotton, tapestry weave, Gift of Dr. Lillian Malcove, 58.50.17

Two examples of cochineal carmine dying from its origins in South America and later in Europe

Artist unknown, Square of Silk, 17th century, Brocaded silk with gilt, Gift of the Irene Leache Memorial Foundation, 2014.3.25

By 1625, cochineal was unquestionably the most popular red colorant—as seen in this brilliantly colored seventeenth century square of silk.[vii] Kermes had become prohibitively expensive and often adulterated with madder.[viii] While the Spanish Royal family had long asserted to be blue-blooded, the discovery of cochineal had them and others seeing red. Throughout the sixteenth century, Spain was in conflict with much of Europe, including England and the Dutch Netherlands. Despite the ongoing Anglo-Spanish War, English leaders deemed that the trade in Spanish cochineal was so crucial to its economy that it must be continued. French ships were used to secretly trade cochineal between the Spanish and English while Queen Elizabeth I gave her blessing to English pirates to capture and profit from Spanish ships of cochineal. The Dutch also endorsed this piracy while the French were known to smuggle their ships into port to avoid paying extreme taxes on such luxury goods.[ix] Queen Elizabeth’s famed Armada Portrait, commemorating the defeat of the Spanish, showcases her surrounded by an interior dripping with red fabrics—a symbol of her status and perhaps a triumph over the Spanish monopoly on cochineal.

Attributed to George Gower (c.1546–1596). C.1588. Woburn Abbey. Oil on Oak. Via Wiki Images. CC.

Painters Get Scrappy Too: Recycling Red

For the humble painter, these raging (trade) wars meant that both kermes and the latter cochineal were inaccessible colors—at least directly. From the fourteenth to the seventeenth century, very thrifty painters collected red rags and cuttings from which they extracted the precious carmine color. Caustic baths of lye made from water and wood ash would dissolve the outer protein layers of silk, readily releasing the red dye. Alum was then added to precipitate the red dye out of solution, forming a solid particle that could be dried and mixed with oil to make paint. [x] The color could range from purple-red to true-red to orange-red based on preparation.[xi] Madder colored paints were also made this way, despite the more economical cost of the primary dyestuff. Paintings can now be analyzed for traces of silk and wool to confirm the presence and source of these red colors.[xii]

These carmine colors made brilliant, translucent red paints—excellent for glazing red fabrics and rosy cheeks. The red robes of many sitters we see are literally painted with the same colors of the robes they wore. Painters developed means of glazing carmine red lake colors that would allow for maximum saturation of color and economy of materials. Often, several layers of paint were built up, with carmine being reserved for only specific areas of bright or deep red. For areas of red cloth, madder paint glazes—an economical and transparent but duller orange-red—were laid down before a final glaze of brilliant carmine.[xiii] The finished effect is still brilliantly apparent in works like Cornelis van Cleve’s Madonna and Child with the Infant Saint John the Baptist and Angels. The purple shade of carmine is visible in other works like Hendrick ter Brugghen’s Martyrdom of Saint Catharine, a very likely example of New World cochineal. Old World carmine from the kermes appears in the likes of Madonna and Child Flanked by Four Saints (1339–1347) and Portrait of Michele Olivieri (ca. 1450) (pictured above), both opposing a very different shade of red: the brilliant but opaque orange-red vermilion. This and other more economical pigments like red lead and red earth oxides (red ochres) were commonly used to tint layers of base color, such as those of flesh tones, that were more heavily employed across a composition.

Cornelis van Cleve (Flemish, 1520–1567), Madonna and Child with the Infant Saint John the Baptist and Angels, ca. 1550, Oil on wood, Gift of the Irene Leache Memorial Foundation, in memory of Frances Rogers Curd, 2014.3.4

Hendrick ter Brugghen (Dutch, 1588–1629), The Martyrdom of Saint Catherine, ca. 1618–1620, Oil on panel, Gift of Walter P. Chrysler, Jr., 71.2076

Fading Away: The End of Carmine Colors

Unlike many colors that were rapidly replaced in the nineteenth century by synthetic coal tar dyes, cochineal dye remained in high demand with use peaking in the latter part of the nineteenth century.[xiv] Despite its long-lived success, it was not without problems. The natural dye was famously not lightfast.[xv] The most famous examples are found in the works of Sir Joshua Reynolds. The subjects in his works appear like grey ghosts, exhibiting a rapid fading that occurred even during his own life, “I tried every new color; and often, as is well known, failed.” [xvi] His portrait of George Clive and his family and maid is a good example. The carmine used to color the family’s skin faded severely in stark contrast to the maid’s well-preserved complexion, modeled in much more stable earth colors. Our own Madonna and Child from the early sixteenth century possibly shows signs of fading red dye pigments as well, appearing quite dull compared to the bright red color more typically associated with carmine or even madder.

Follower of the Master of The Legend of the Magdalene (Flemish, active ca.1485– ca. 1530), Virgin and Child, ca. 1520–25, Oil on panel, Gift of the Irene Leache Memorial Foundation, 2014.3.3

With lightfastness and the Spanish monopoly a continued issue, alternative means of creating lake reds were in high demand by the nineteenth century.[xvii] Working with inexpensive madder, new, more richly colored isolates were discovered: purpurin and the more popular alizarin. Synthetic alizarin crimson replaced natural isolates in 1868 as an even more economical and purely saturated color.[xviii] This nineteenth century red color remains a staple of artists’ and conservators’ palettes along with many other new lightfast, synthetic red compounds. The insect-based red pigment that once fueled centuries of smuggling and piracy now finds limited use in food coloring, cosmetics, and traditional crafts.[xix] However, some contemporary artists like Faig Ahmed continue to explore the potential use of these antiquated, but brilliant natural red dyes in works like Virgin.

Faig Ahmed (Azerbaijani, born 1982), Virgin, 2017, Handmade woolen carpet, Museum purchase © Faig Ahmed, 2017.24

–Brandan Finney, NEH Conservation Fellow

[i] Helmut Schweppe and Heinz Roosen-Runge, ‘Carmine – Cochineal Carmine and Kermes Carmine’, in Artists’ Pigments: A Handbook of Their History and Characteristics, ed. by Robert L Feller (Washington DC: National Gallery of Art, Washington DC, United States, 1986), p. pp.255–283.

[ii] Schweppe and Roosen-Runge.

[iii] Schweppe and Roosen-Runge.

[iv] Jo Kirby, Marika Spring, and Catherine Higgitt, ‘The Technology of Red Lake Pigment Manufacture: Study of the Dyestuff Substrate,’ National Gallery Technical Bulletin, 26 (2005), 71–87 <http://www.jstor.org/stable/42616314>.

[v] Schweppe and Roosen-Runge.

[vi] Raymond L. Lee, ‘American Cochineal in European Commerce, 1526–1625,’ The Journal of Modern History, 23.3 (1951), 205–24 <http://www.jstor.org/stable/1872704>.

[vii] Lee.

[viii] Maria Luisa Vazquez de Agredos Pascual and others, ‘Kermes and Cochineal; Woad and Indigo. Repercussions of the Discovery of the New World in the Workshops of European Painters and Dyers in the Modern Age’, Arché, 2, 2007, 131–36.

[ix] Lee.

[x] Kirby, Spring, and Higgitt, ‘The Technology of Red Lake Pigment Manufacture: Study of the Dyestuff Substrate’.

[xi] Schweppe and Roosen-Runge.

[xii] Kirby, Spring, and Higgitt, ‘The Technology of Red Lake Pigment Manufacture: Study of the Dyestuff Substrate.’.

[xiii] Kirby, Spring, and Higgitt, ‘The Technology of Red Lake Pigment Manufacture: Study of the Dyestuff Substrate’.

[xiv] Lee.

[xv] Schweppe and Roosen-Runge.

[xvi] Ashok Roy and others, ‘Joshua Reynolds in the National Gallery and the Wallace Collection’, National Gallery Technical Bulletin, 35 (2014), 1–111 <http://www.jstor.org/stable/44678721>.

[xvii] Jo Kirby, Marika Spring, and Catherine Higgitt, ‘The Technology of Eighteenth– and Nineteenth–Century Red Lake Pigments’, National Gallery Technical Bulletin, 28 (2007), 69–95 <http://www.jstor.org/stable/42616200>.

[xviii] Kirby, Spring, and Higgitt, ‘The Technology of Eighteenth– and Nineteenth–Century Red Lake Pigments’.

[xix] Schweppe and Roosen-Runge.

Bibliography

Kirby, Jo, Marika Spring, and Catherine Higgitt, ‘The Technology of Eighteenth– and Nineteenth–Century Red Lake Pigments’, National Gallery Technical Bulletin, 28 (2007), 69–95 <http://www.jstor.org/stable/42616200>

———, ‘The Technology of Red Lake Pigment Manufacture: Study of the Dyestuff Substrate’, National Gallery Technical Bulletin, 26 (2005), 71–87 <http://www.jstor.org/stable/42616314>

Lee, Raymond L, ‘American Cochineal in European Commerce, 1526-1625’, The Journal of Modern History, 23.3 (1951), 205–24 <http://www.jstor.org/stable/1872704>

Roy, Ashok, Susan Foister, Lucy Davis, Alexandra Gent, and Rachel Morrison, ‘Joshua Reynolds in the National Gallery and the Wallace Collection’, National Gallery Technical Bulletin, 35 (2014), 1–111 <http://www.jstor.org/stable/44678721>

Schweppe, Helmut, and Heinz Roosen-Runge, ‘Carmine – Cochineal Carmine and Kermes Carmine’, in Artists’ Pigments: A Handbook of Their History and Characteristics, ed. by Robert L Feller (Washington DC: National Gallery of Art, Washington DC, United States, 1986), p. pp.255-283

Vazquez de Agredos Pascual, Maria Luisa, Ma Domenech Carbo, Dolores Julia Yusa Marco, Sofia Vicente Palomino, and Laura Fuster Lopez, ‘Kermes and Cochineal; Woad and Indigo. Repercussions of the Discovery of the New World in the Workshops of European Painters and Dyers in the Modern Age’, Arché, 2, 2007, 131–36