- Open today, 10 am to 5 pm.

- Parking & Directions

- Free Admission

The History of Art in Color

From the Shadows to the Foreground: Black Pigments and the Fight for Equal Rights in Western Art

While it’s often touted that black is not a color, the use of black pigments is as old as humankind itself. These ancient pigments have history that is as rich and deep as their velvety hue. The word black today has also become especially important, not considering the materials of art making but in the discussion of racial politics that reverberates across the globe. A sampling of works from the Chrysler Museum of Art depicts the history of social justice for people of color in Western society and illustrates the use of black pigments in crafting these images.

Africa and Europe in the Early Modern Period

In a time of European colonialism and widespread slave trade, Black people were often depicted in less-than-kind manners. Caricature-like depictions are present throughout early Renaissance drawings and paintings that attest to the European mindset of colonialism and White supremacy. In contrast, one figure emerged in the fifteenth century that would move beyond these damaging images: that of the Black Magus Balthazar. In the Middle Ages, the iconography of the three kings Caspar, Melchior, and Balthazar visiting the Christ child was conceived. Previously, the Bible offered no specific number or description of visitors. [1] Only in the eighth century, a writer identified as Pseudo-Bede (a contemporary author writing as Saint Bede) first described one Magus as having a dark complexion.[2] Typical depictions from this period feature a very European-looking suite of guests, leaving out this man of color, as seen in later works like our Book of Hours (ca. 1480). However, other fifteenth-century works were marked by an important change in this iconography: Balthazar’s transition from a White man to the Black king of Africa.[3]

Master of the Rouen Echevinage (French, active ca. 1475), Book of Hours (detail), ca. 1480, Tempera, liquid gold, and brown ink on vellum, Gift of the Irene Leache Memorial Foundation to honor the memory of Alice Rice Jaffé, 2014.3.6

Giovan Filippo Criscuolo (Italian, 1495-1584), Adoration of the Magi, ca. 1545, Oil on panel, Gift of Walter P. Chrysler, Jr., 78.294

One of our oldest depictions of a Black person, the Adoration of the Magi by Giovan Filippo Criscuolo (ca. 1545), features the now well-known Magus Balthazar. Perhaps the Magus is made most famous in the work of Hieronymus Bosch at the Prado Museum. Many of you might recognize the iconography of this scene. The adoration of the Christ child was one of the most popular subjects of sixteenth-century images, distributed widely through both prints and paintings. The elevation of a Black man to a position of status, particularly one of great importance and popularity within the Christian faith in Early Modern Europe, can perhaps be seen as an early step in the fight for equal status for people of color in Western society.[4] Unfortunately, Balthazar’s placement in these religious iconographies had more to do with Europe’s exploitation of the African continent, and thus requires broader contextualization.

Detail from Triptych of the Adoration of the Magi by Hieronymus Bosch, Oil on panel, ca. 1485–1500, Museo Nacional del Prado. https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=15384563

In our panel, Balthazar’s otherness is marked by his skin color in relation to the other figures and his fanciful Eastern-style costuming. His turban particularly marks him out as a non-Christian,[5] a peculiar attribute for one bringing gifts to the Christ child. A critical reading of this iconography suggests that Balthazar as the King of Africa crystallized during a period of intense colonization of Africa by European countries like Portugal. [6] Furthermore, the conversion of African peoples to Christianity was a large concern for Christian nations of Europe.[7] In this context, the figure of Balthazar pledging allegiance to the Christ child may be understood as a symbol for Christianity’s dominance over the globe and other religions. For many people, this dominance became a grim reality, with free Christian converts being welcomed to Europe and others enslaved.[8]

Giovan Filippo Criscuolo (Italian, 1495–1584), Adoration of the Magi (detail), ca. 1545, Oil on panel, Gift of Walter P. Chrysler, Jr., 78.294

Another work in our collection, Guardroom Scene with African Soldier Cleaning Pistols by Abraham Teniers (ca. 1650–65), helps to illuminate the reality of Black Africans in Europe during this time. While it may be tempting to read nearly any image with a Black person working, attending, or serving in Old Master painting as an enslaved person, the reality of slavery and race was complex in Early Modern Europe. Black people living in Europe represented those enslaved and those living free(d).[9] In fact, by the end of the sixteenth century, the professionalism of people of color was underway with the first Black lawyers, teachers, and artists.[10] Several instances of formerly enslaved Black men becoming guards at courts[11] suggest that our painting of a guardroom depicts the same.

Abraham Teniers (Netherlandish, 1629–1670). Guardroom Scene with African Soldier Cleaning Pistols, ca.1650–65, Oil on panel, Museum purchase, 2020.7

Abraham Teniers (Netherlandish, 1629–1670), Guardroom Scene with African Soldier Cleaning Pistols (detail), ca.1650–65, Oil on panel, Museum purchase, 2020.7

Despite the gains made in this period by people of color in Europe, most still faced blatant discrimination for their dark skin. European writers derogatorily described African people as having skin “black as coal.”[12] European painters, in fact, had been using coal to beautifully render all skin tones in the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries. The pigment was widely recommended for its ability to create a warm, transparent glaze of shadows. Black pigments appear to be somewhat of a fascination for sixteenth-century painters. They consistently used an incredibly wide range of options. Many black pigments are the product of combustion—the burning of ivory, bones, vines, wood, or fruit pits to produce carbonized black organic matter. Because of its unique chemical composition, each can impart slightly different variations. Bone black is warmer in hue than ivory black that is bluer in color, for instance.[13] Regardless of origin, these organic black pigments are all incredibly stable, nearly impervious to any fading by light. In fact, NASA utilizes them as a solar shield for satellite components.[14] Like coal, other black pigments were also mined. Minerals like pyrolusite were popular; they sped the drying of oil paint, a usually painfully slow process when only organic black pigments like ivory were involved. [15] These black pigments have continued to be used for millennia now, particularly the carbon-based ones found in paintings, prints, and drawings until the present.

Brown Coal by Luis Miguel Bugallo Sánchez (Wiki Commons) – Own work, CC BY-SA 3.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=355360

Pyrolusite. By Aram Dulyan – Own work, Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=577933

In the Shadows: Black in the Eighteen and Nineteenth Centuries

The same black pigments that were used to construct the works of the Old Masters continued to be widely employed in the centuries that followed. Carbon blacks that could be produced from a nearly infinite range of organic materials were enduringly popular. With the new availability of coal and petroleum products in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, many carbon blacks became the product of these fossil fuels. In the nineteenth century, artists were often trying to achieve rich shadows in their paintings and coal tar and bitumen proved useful as transparent glazing pigments.[16],[17] These pigments produced warm brown-black colors like those in Dem Was Good Ole Times by Thomas Hovenden (ca. 1882). Hovenden’s painting preserves a period of conflicting ideals in American history, reflected in the artist’s sympathetic portrayal of the figure on the one hand and his chosen title in the stereotypical vernacular, which was commonly used to portray African Americans in a derogatory way. Similarly, despite the abolition of slavery in the United States in 1865, segregation and other forms of discrimination continued to be practiced, legislated, and reinforced by racist imagery. [18]

Thomas Hovenden (American, 1840–1895), Dem Was Good Ole Times, 1882, Oil on canvas, Museum purchase with Funds Provided by The Chrysler Museum Landmark Communication Art Trust; An Anonymous Donor; Mr. and Mrs. Richard M. Waitzer; Mr. and Mrs. Richard F. Barry III; and The Museum’s Accession Fund, 92.49.1

Hovenden provided what he considered to be sincere portraits of Black American life in this time, against the popular caricatures of the era. In this picture, he paints his neighbor Samuel Jones, a real person, with all the care and respect a painter would employ for a society portrait. However, despite the work’s bordering of portraiture, the sitter has been cast as a character. The work presents the stereotype of an old Black man and the musician, an image popularized at the time through songs, novels, and performances. The Black musician’s moniker, the banjo, developed into a polarizing symbol by the end of the nineteenth century. The instrument was increasingly employed in racist stereotypes, but also held an important place in contemporary African American culture. Originating in West Africa, the tradition of banjo playing had been brought to America by enslaved peoples.[19] The teaching of this musical skill is illustrated, without the use of stereotypical characters, in works like the Banjo Lesson (1893) by the African American artist Henry Ossawa Tanner.

Henry Ossawa Tanner, The Banjo Lesson, 1893, Oil on canvas, Hampton University Museum. Image via WikiArt.

In Dem Was Good Ole Times, along with Hovenden’s title, the banjo conveys nostalgia for the ideals of the American South as it was before the Emancipation Proclamation. Images like these appealed to White collectors, critics, and the general public, offering a guilt-free vision of only recently freed Black Americans.[20] Despite stepping out from the shadows from behind those who owned or employed them, depictions of Black people were often still produced through the lens of White supremacy that still pervaded this era.

It’s There in Black and White: The Power of Photography in the Civil Rights Movement

With the invention of a new medium, the color black took on new meaning. Black and white photographs gave rise to the concept of black and white as the harsh purveyor of truths. In 1960s America, newspapers were the main source of coverage, with large photos splashed across many pages. Across these pages, the Civil Rights Movement was disseminated from small pockets in the South broadly across the country.[21] Black people came to the front of the image, the front of the news, and the front of the discussion.

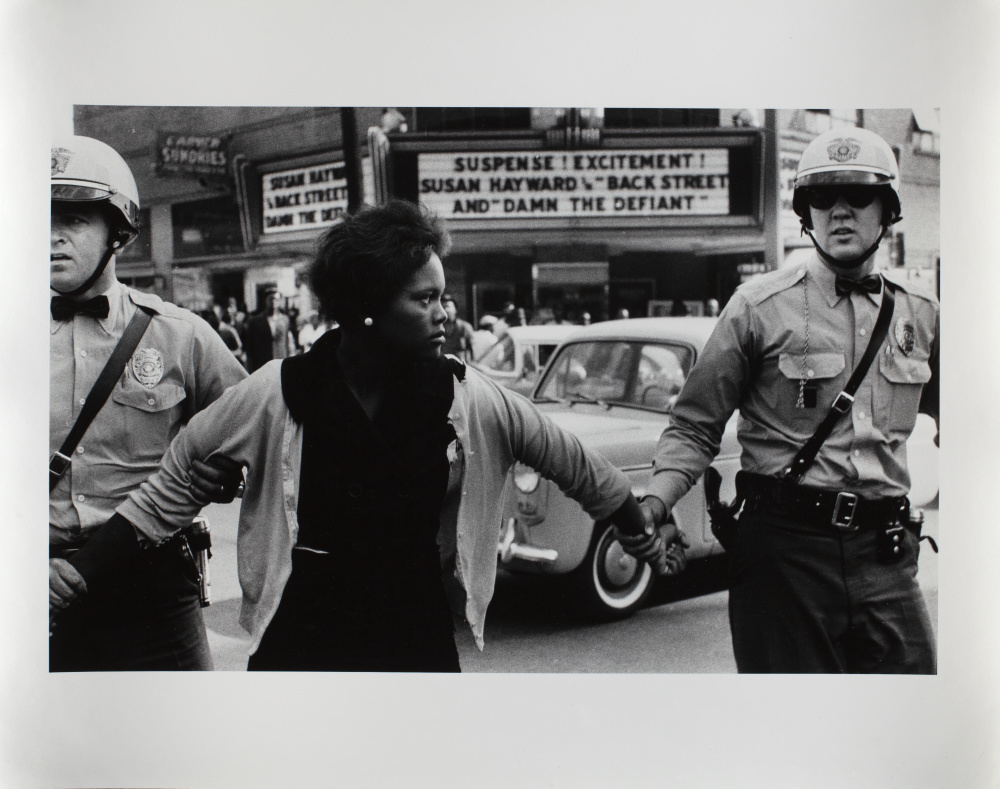

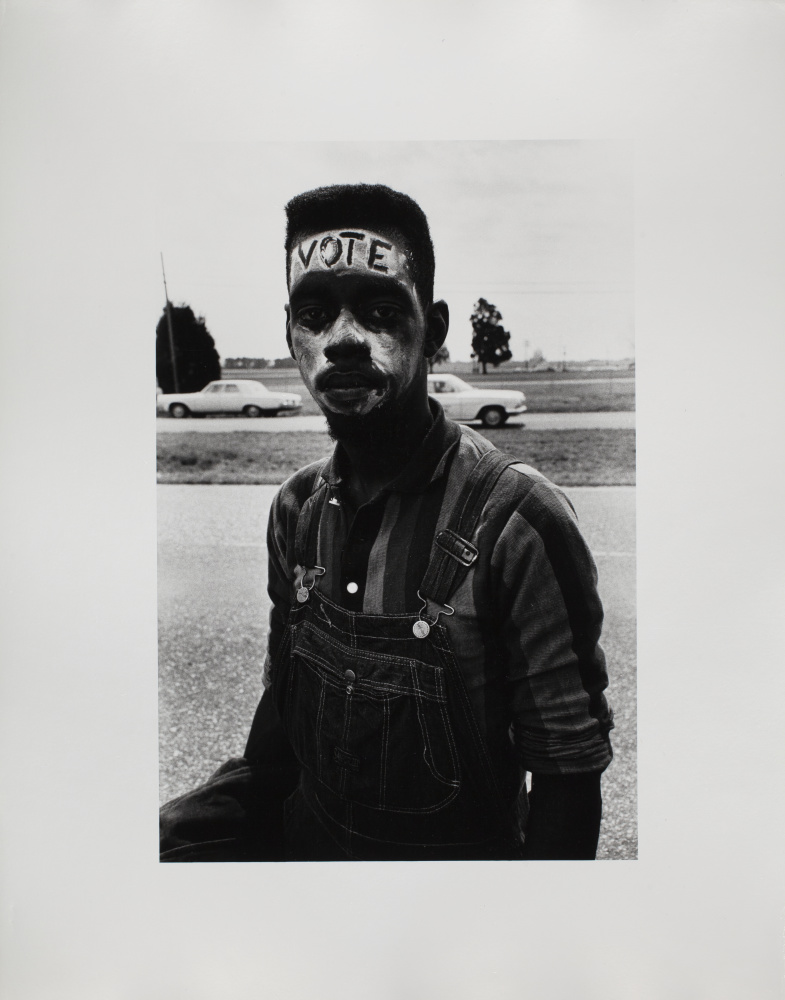

As with modern media, there was demand for highly polarizing images—those showing violence, marches, and sit-ins. Such images are presented in the works of Charles Moore, whose work was picked up by Life magazine, and art photographer Bruce Davidson.[22]

Charles Moore (American, 1931–2010), Demonstrators attacked with water cannons, Kelly Ingram Park, Birmingham, Alabama, 1963, Gelatin silver print, Museum purchase in memory of Alice R. and Sol B. Frank © Charles Moore, courtesy Black Star, 97.30

Bruce Davidson (American, b. 1933), Untitled, from the Times of Change series, 1963, Gelatin silver print, Anonymous gift, 2018.44.282

These images can be difficult to look at with modern eyes. They capture Black people in pain, often void of humanity. Despite how we might now interpret these images, they are credited with playing a critical role in the Civil Rights Movement. Photographs of victimized Black Americans in the early 1960s brought to light the everyday injustices they faced in the South. Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. personally recognized the importance of these violent images as a permanent and incontestable record of African American struggles and thus strongly advocated for their use in his book Why We Can’t Wait (1964). With their visual immediacy, the use of these pictures in newsprint transmitted an unseen reality to many White Americans. [23] [24]

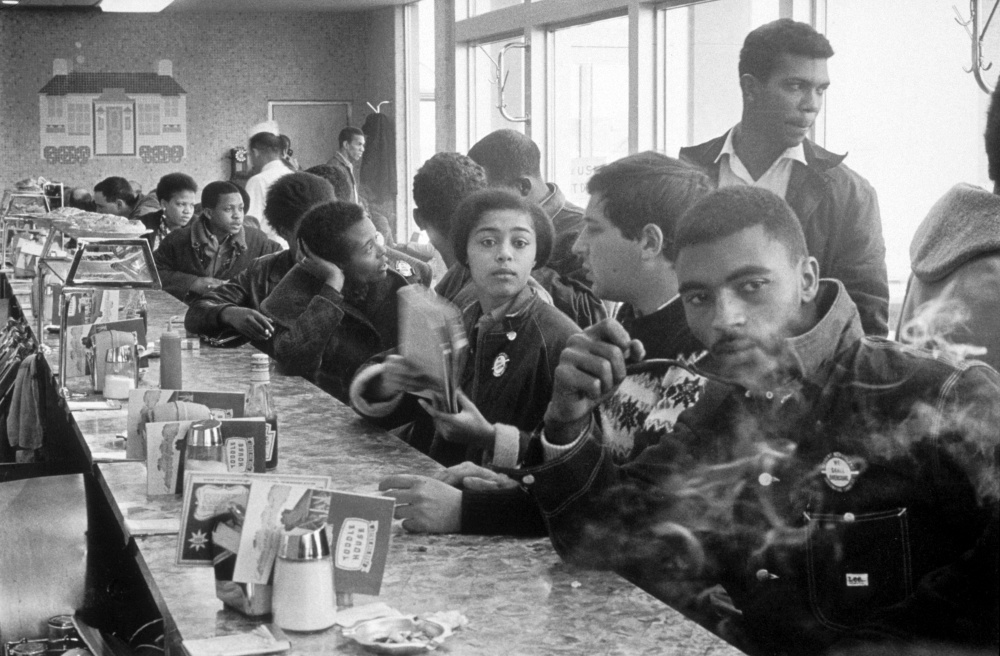

Just as video footage today has been a call to action, these still images sparked others to participate in the Civil Rights Movement. Furthermore, in an era that was greatly less connected than ours, these images served as instruction for new activists on how to participate in marches, protests, and sit-ins. In this regard, the reformist group Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) was hugely influential from the early 1960s onward, forming a collective of photographers that endeavored to capture these images for a global audience. Works like those of Danny Lyon present the friendship these photographers had with fellow activists, getting right into the action. [25] [26]

Danny Lyon (American, b. 1942), A Toddle House in Atlanta Has the Distinction of Being Occupied during a Sit In by Some of America’s Most Effective Organizers. In the Room Are Taylor Washington, Ivanhoe Donaldson, Joyce Ladner, John Lewis behind Judy Richardson, George Green, and Chico Neblett, 1963–1964, printed 1999, Gelatin silver print, Museum purchase, in memory of Alice R. and Sol B. Frank, and with funds provided by Patricia L. Raymond, M.D, © Danny Lyon / Licensed by Magnum Photos, 2000.14.25

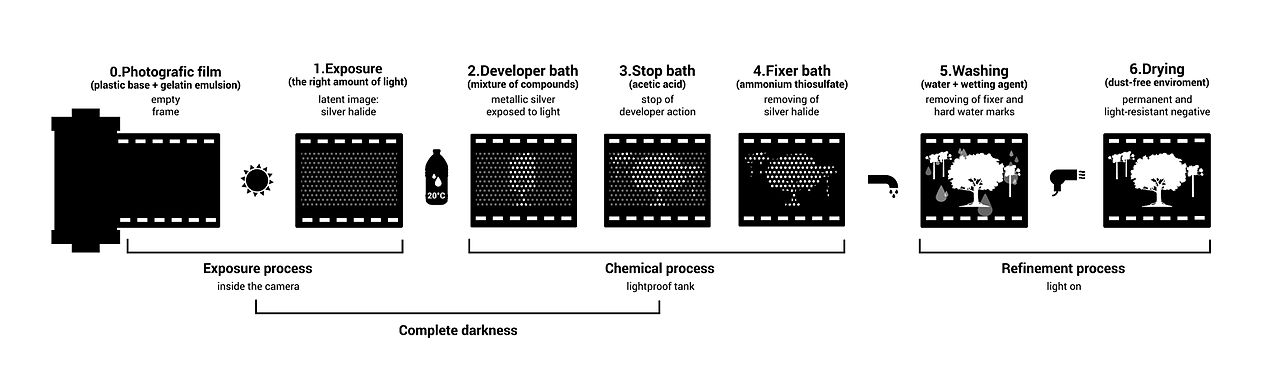

In the age of smartphones, getting this kind of documentary image has become incredibly simple; but in the 1960s, it required a good deal of equipment, a few chemicals, and more than a bit of patience. By the 1960s, 35mm cameras had taken over the market. Affordable; lightweight; and easy to load, focus, and shoot, they allowed nearly anyone to own and operate a camera. Inside, a spool of cellulose triacetate negatives held an emulsion of light-sensitive silver halide particles. When exposed to light, the particles start a reaction that causes them to darken. After shooting, these negatives were developed and fixed in a series of aqueous chemical baths that produced the final transparent image.

Photograph Developing by Marianna Caserta, DensityDesign Research Lab – Own work, CC BY-SA 4.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=37058198

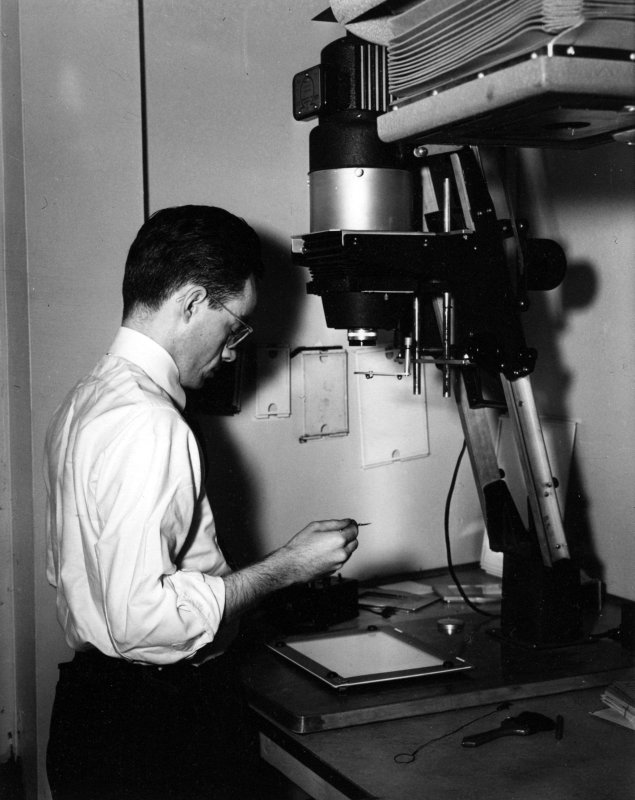

For most of the twentieth century, the image was then made into a silver gelatin print. A paper coated with the same light-sensitive silver halides in a thin film of gelatin was exposed to the negative using an enlarger (a special projector). This process allowed the photo to be scaled to the desired size and manipulated with techniques that allowed for more or less light to be projected on the final paper. Those techniques were the precursors to Photoshop®. The paper photograph was then developed and fixed in the same manner as the negatives. As there was no one-hour photo service, the SNCC put together their own darkrooms to support their photographers. [27]

Photographic Enlarger in Use ca. 1950–51 by Don O’Brien. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:EnlargingANegativeC1950.jpg

Unlike modern JPEG images that become pixelated when stretched, true photographic negatives hold an incredible amount of visual detail, allowing for the creation of super sharp, large-scale prints like those that we now have in our collection. During the 1960s, however, most of these images would have been circulated in low-quality halftone and offset prints found in newspapers. Halftoning is a means of making a metal printing plate from a photograph that, when printed, creates a familiar pattern of dots found in many printing methods still used today.

Detail of a halftone printed image from a newspaper c. 1920–30. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Halftone,_Gaussian_Blur.jpg

Into Full Color: Self-Representation and Modern Materials

From photography in the Civil Rights era emerged a growing trend—that of African Americans cultivating their own images. The Black Power movement emerged in 1966 as a response to the passing of the Voting Rights Act of 1965 and the lack of agency seen in violent media photography. The Black Power movement celebrated Black culture and humanity, putting particular emphasis on Black art by Black people for Black people. This, in turn, paved the way for the Black Arts Movement of the 1970s. [28]

Because of its association with truth, photography was seen as an antidote to decades of harmful stereotypes. [29] Photographers like Kwame Brathwaite, working from the late 1950s onwards, helped popularize the phrase “Black is beautiful,” working with artists and organizations to showcase natural hairstyles and clothing inspired by African ancestry.[30] By the end of 1960s, the afro had become a popular hairstyle, both fashionable and political.[31]

Kwame Brathwaite (American, born 1938), Untitled (Model who embraced natural hairstyles at AJASS photoshoot), 1970, printed 2018, Archival pigment print, Museum purchase, in memory of Alice R. and Sol B. Frank, © Kwame Brathwaite, 2019.34.3

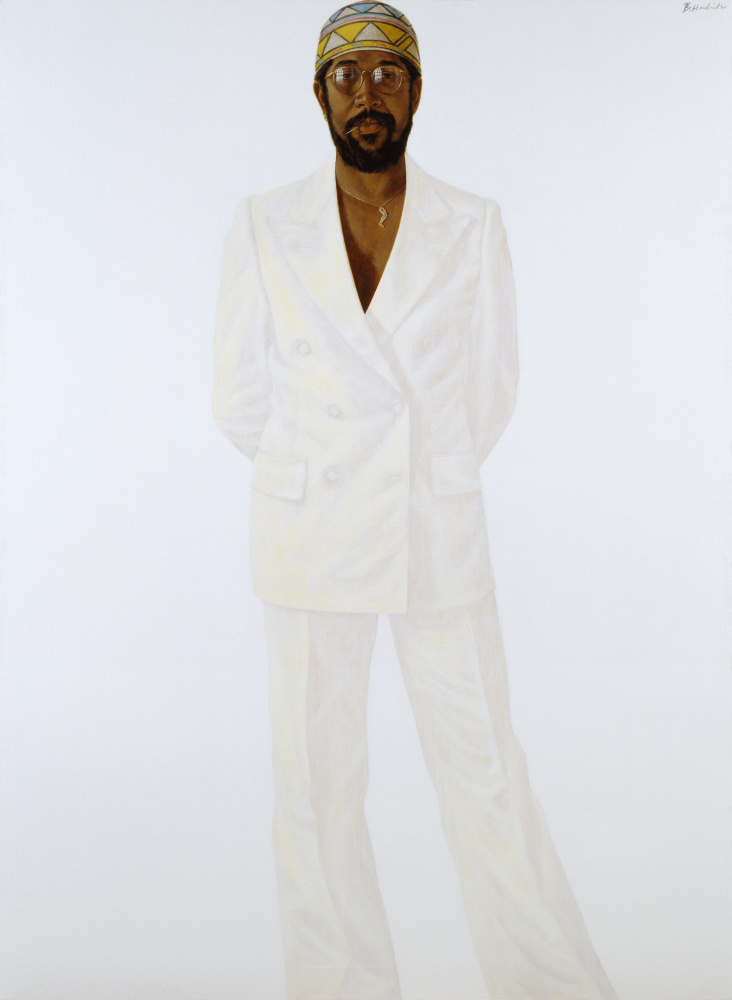

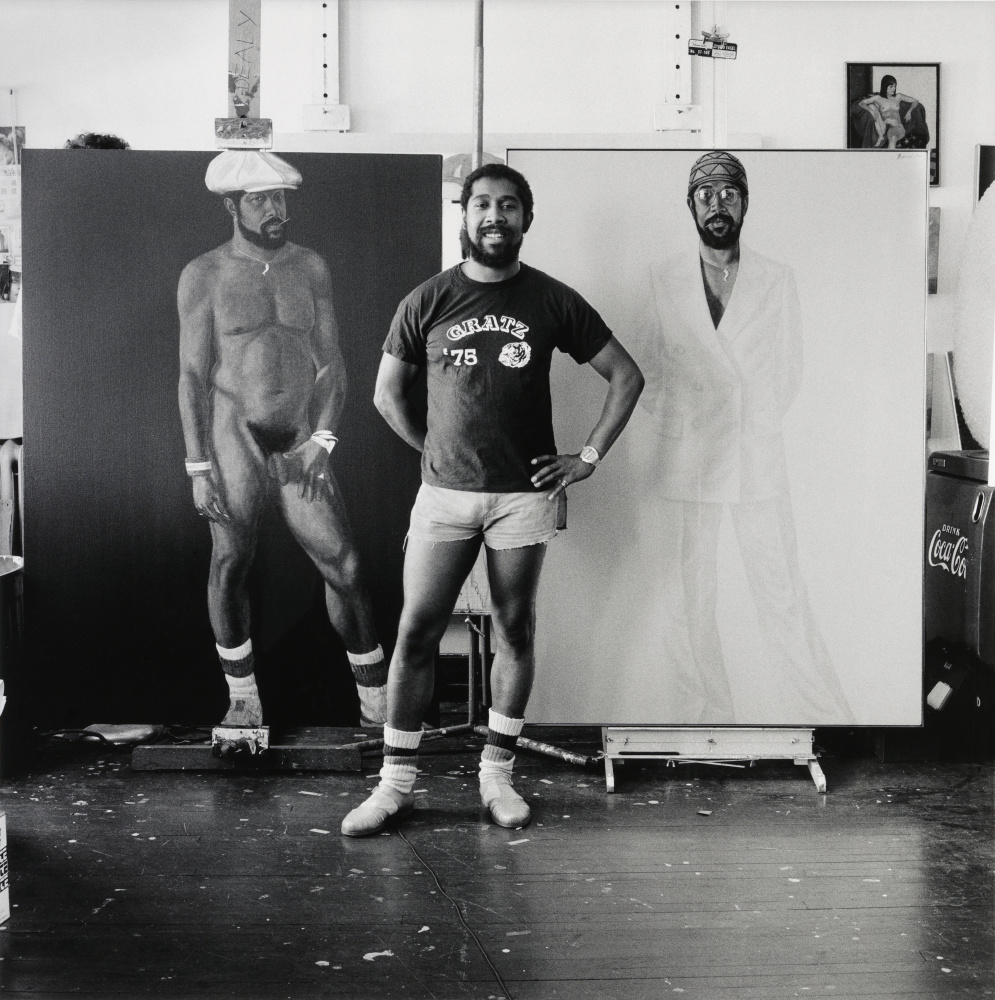

The 70s were also the era of a cool new aesthetic for men as portrayed in the paintings of Barkley L. Hendricks.

Barkley L. Hendricks (American, 1945–2017), Slick, 1977, Oil, acrylic and Magna (acrylic resin paint) on canvas, Gift of the American Academy and Institute of Arts and Letters, New York © Barkley L. Hendricks, 78.62

Barkley L. Hendricks (American, 1945–2017). Self Portrait., 1977, printed 2013, Digital chromogenic print., Museum purchase, in memory of Alice R. and Sol B. Frank © Barkley Hendricks, Courtesy of the artist and Jack Shainman Gallery, NY, 2013.8

As legislature and social codes were updated in the twentieth and twenty-first centuries, so were the technologies that allowed artists to create these works. Mars black— a synthetic, high-opaque, fast-drying, black pigment—was introduced in the middle of the twentieth century.[32] Another addition, Black Spinel (manganese ferrite black) was the Vantablack® of its time. It’s the “truest” black pigment readily available, reflecting nearly no color.[33] These pigments were loaded into new mediums like the water-based acrylics we are familiar with today and their solvent-born precursor Magna®, as seen in the multimedia painting technique of Slick.

Many objects we now call photos or photographs have also received an update. They, in fact, are not photographs (“images made by light”). They are prints, reproductions made with mechanical and digital means. The number of processes and variations available to reproduce digital images taken by cameras is immense, but Inkjet has far become the most important of these processes. In the ‘90s, Inkjet printers could not produce photo-quality prints. Despite their colorful nature, black pigments played a critical role in this. Inkjet printers previously were only capable of delivering a dot pattern of dyes to a surface. Black dyes could not match the deep intensity of traditional photograph processes, so Inkjets remained the mainstay of office printing. Epson and Kodak pioneered the use of carbon black pigment in these printers along with the other three colors in a cyan, magenta, yellow (CMYK) print.[34] This ancient pigment received an update too, now produced in industrial furnaces with scorching hot temperatures, natural gas, and oxygen. In these furnaces, petroleum products are combusted into a powder of pure carbon that is fine enough to be carried in a microdroplet of ink.[35] Archival pigment prints, like those used to produce our contemporary print from the 1970s negative of Untitled (Model who embraced natural hairstyles at AJASS photoshoot), are now largely made using Inkjet printing. These prints will likely prove to be more stable and lightfast than the traditional color photographs that utilized light-sensitive dyes to create color.

Black pigments continue to evolve through the addition of Vantablack®. Like many of the black pigments used throughout history, Vantablack® is based on carbon. Unlike all other black pigments, Vantablack is composed of carbon nanotubes that channel nearly all visible light into the pigment’s structure where it is absorbed. The result is a black hole-like effect in which no light escapes—the darkest black possible.

As these materials continue to evolve, hopefully so will all our ability to recognize and challenge systemic racism. Today, as global protests demand action to be taken, images like those from the 1960s continue to resonate with meaning in 2020.

Bruce Davidson (American, b. 1933), Untitled, from the Times of Change series, 1965, Gelatin Silver Print, Anonymous gift, 2018.44.359

Join us next week to learn about the other colors that make up an archival pigment print. What are Arylide yellow, phthalocyanine cyan, and Quinacridone Magenta? Find out with Modern Colors: the Electric Rainbow

–Brandon Finney, NEH Conservation Fellow

Bibliography

‘Balthazar: A Black African King in Medieval and Renaissance Art. Published Online 2019’ (Los Angeles: J. Paul Getty Museum)

Devisse, Jean, and Michel Mollat, ‘The African Transpossed’, in The Image of Black in Western Art. Vol. 2, ed. by Ladislas Bugner (Cambridge, Mass: Harvard Univ. Press, 1979), pp. 161–254

Europe, Revealing the African presence in Renaissance, ‘Free Men and Women of African Ancestry in Renaissance Europe’, in Revealing the African Presence in Renaissance Europe, ed. by Joaneath A Spicer (Baltimore: Walters Art Museum, 2012), pp. 81–98

Hillman, Betty Luther, ‘Everyone Should Be Accustomed to Seeing Long Hair on Men by Now’, in Dressing for the Culture Wars, Style and the Politics of Self-Presentation in the 1960s and 1970s (University of Nebraska Press, 2015), pp. 123–54 <https://doi.org/10.2307/j.ctt1d9nj19.10>

‘Kwame Brathwaite: The Artist’, Kwamebrathwaite.Com <https://www.kwamebrathwaite.com/about> [accessed 11 July 2020]

Lowe, K J P, ‘The Lives of African Slaves and People of African Descent in Renaissance Europe’, in Revealing the African Presence in Renaissance Europe, ed. by Joaneath A Spicer, 3rd Printi (Baltimore: Walters Art Museum, 2012), pp. 13–34

Pastoureau, Michel, Black : The History of a Color (Princeton, N.J: Princeton University Press, 2009)

Peplow, Mark, ‘The Reinvention of Black’, Nautilus, 2015 <http://nautil.us/issue/27/dark-matter/the-reinvention-of-black> [accessed 3 July 2020]

Pinson, Yona, ‘Connotations of Sin and Heresy in the Figure of the Black King in Some Northern Renaissance Adorations’, Artibus et Historiae, 17.34 (1996), 159–75 <https://doi.org/10.2307/1483528>

‘Prehistoric Cave Pigment to Shield ESA’s Solar Orbiter’, The European Space Agency , 2014 <http://www.esa.int/Enabling_Support/Space_Engineering_Technology/Prehistoric_cave_pigment_to_shield_ESA_s_Solar_Orbiter> [accessed 12 July 2020]

Printing Processes and Printing Inks, Carbon Black and Some Nitro Compounds, IARC Monographs on the Evaluation of Carcinogenic Risks to Humans, No. 65. (Lyon, 1996) <https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK424338/> [accessed 12 July 2020]

Raiford, Leigh, Imprisoned in a Luminous Glare (University of North Carolina Press, 2011) <http://www.jstor.org/stable/10.5149/9780807882337_raiford>

Shakhnovich, Alex, and James Belmont, ‘Pigments for Inkjet Applications’, in The Chemistry of Inkjet Inks (WORLD SCIENTIFIC, 2009), pp. 101–22 <https://doi.org/doi:10.1142/9789812818225_0006>

‘Spinel Black’, ColorLex <https://colourlex.com/project/spinel-black/> [accessed 12 July 2020]

Spring, Marika, Rachel Grout, and Raymond White, ‘“Black Earths”: A Study of Unusual Black and Dark Grey Pigments Used by Artists in the Sixteenth Century’, National Gallery Technical Bulletin, v.24, 24 (2003), pp.96-24 ills. (23 color), 83 refs.

Terhune, Anne Gregory, Patricia Smith Scanlan, and Elizabeth Johns, ‘Painting the “Good Ole Times” ’, in Thomas Hovenden, His Life and Art (University of Pennsylvania Press, 2006), pp. 95–125 <http://www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctt3fhcq5.10>

Thornton, Davi Johnson, ‘The Rhetoric of Civil Rights Photographs: James Meredith’s March Against Fear’, Rhetoric and Public Affairs, 16.3 (2013), 457–88 <https://doi.org/10.14321/rhetpublaffa.16.3.0457>

Townsend, Joyce H, Leslie Carlyle, Narayan Khandekar, and Sally Woodcock, ‘Later Nineteenth Century Pigments: Evidence for Additions and Substitutions’, The Conservator, 19.1 (1995), 65–78 <https://doi.org/10.1080/01410096.1995.9995096>

White, Raymond, ‘Brown and Black Organic Glazes, Pigments and Paints’, National Gallery Technical Bulletin, 10 (1986), 58–71 <http://www.jstor.org/stable/42616039>

[1] ‘Balthazar: A Black African King in Medieval and Renaissance Art. Published Online 2019’ (Los Angeles: J. Paul Getty Museum).

[2] Yona Pinson, ‘Connotations of Sin and Heresy in the Figure of the Black King in Some Northern Renaissance Adorations’, Artibus et Historiae, 17.34 (1996), 159–75 <https://doi.org/10.2307/1483528>.

[3] ‘Balthazar: A Black African King in Medieval and Renaissance Art. Published Online 2019’.

[4] Jean Devisse and Michel Mollat, ‘The African Transpossed’, in The Image of Black in Western Art. Vol. 2, ed. by Ladislas Bugner (Cambridge, Mass: Harvard Univ. Press, 1979), pp. 161–254.

[5] ‘Balthazar: A Black African King in Medieval and Renaissance Art. Published Online 2019’.

[6] Devisse and Mollat.

[7] K J P Lowe, ‘The Lives of African Slaves and People of African Descent in Renaissance Europe’, in Revealing the African Presence in Renaissance Europe, ed. by Joaneath A Spicer, 3rd Printi (Baltimore: Walters Art Museum, 2012), pp. 13–34.

[8] ‘Balthazar: A Black African King in Medieval and Renaissance Art. Published Online 2019’.

[9] ‘Balthazar: A Black African King in Medieval and Renaissance Art. Published Online 2019’.

[10] Lowe.

[11] Revealing the African presence in Renaissance Europe, ‘Free Men and Women of African Ancestry in Renaissance Europe’, in Revealing the African Presence in Renaissance Europe, ed. by Joaneath A Spicer (Baltimore: Walters Art Museum, 2012), pp. 81–98.

[12] Michel Pastoureau, Black : The History of a Color (Princeton, N.J: Princeton University Press, 2009).

[13] Marika Spring, Rachel Grout, and Raymond White, ‘“Black Earths”: A Study of Unusual Black and Dark Grey Pigments Used by Artists in the Sixteenth Century’, National Gallery Technical Bulletin, v.24, 24 (2003), pp.96-24 ills. (23 color), 83 refs.

[14] ‘Prehistoric Cave Pigment to Shield ESA’s Solar Orbiter’, The European Space Agency , 2014 <http://www.esa.int/Enabling_Support/Space_Engineering_Technology/Prehistoric_cave_pigment_to_shield_ESA_s_Solar_Orbiter> [accessed 12 July 2020].

[15] Spring, Grout, and White.

[16] Raymond White, ‘Brown and Black Organic Glazes, Pigments and Paints’, National Gallery Technical Bulletin, 10 (1986), 58–71 <http://www.jstor.org/stable/42616039>.

[17] Joyce H Townsend and others, ‘Later Nineteenth Century Pigments: Evidence for Additions and Substitutions’, The Conservator, 19.1 (1995), 65–78 <https://doi.org/10.1080/01410096.1995.9995096>.

[18] Anne Gregory Terhune, Patricia Smith Scanlan, and Elizabeth Johns, ‘Painting the “Good Ole Times”:’, in Thomas Hovenden, His Life and Art (University of Pennsylvania Press, 2006), pp. 95–125.

[19] Terhune, Scanlan, and Johns, ‘Painting the “Good Ole Times” ‘

[20] Terhune, Scanlan, and Johns, ‘Painting the “Good Ole Times” ‘.

[21] Davi Johnson Thornton, ‘The Rhetoric of Civil Rights Photographs: James Meredith’s March Against Fear’, Rhetoric and Public Affairs, 16.3 (2013), 457–88 <https://doi.org/10.14321/rhetpublaffa.16.3.0457>.

[22] Leigh Raiford, Imprisoned in a Luminous Glare (University of North Carolina Press, 2011) <http://www.jstor.org/stable/10.5149/9780807882337_raiford>.

[23] Thornton.

[24] Raiford.

[25] Thornton.

[26] Raiford.

[27] Raiford.

[28] Raiford.

[29] Raiford.

[30] ‘Kwame Brathwaite: The Artist’, Kwamebrathwaite.Com <https://www.kwamebrathwaite.com/about> [accessed 11 July 2020].

[31] Betty Luther Hillman, ‘Everyone Should Be Accustomed to Seeing Long Hair on Men by Now’, in Dressing for the Culture Wars, Style and the Politics of Self-Presentation in the 1960s and 1970s (University of Nebraska Press, 2015), pp. 123–54 <https://doi.org/10.2307/j.ctt1d9nj19.10>.

[32] Mark Peplow, ‘The Reinvention of Black’, Nautilus, 2015 <http://nautil.us/issue/27/dark-matter/the-reinvention-of-black> [accessed 3 July 2020].

[33] ‘Spinel Black’, ColorLex <https://colourlex.com/project/spinel-black/> [accessed 12 July 2020].

[34] Alex Shakhnovich and James Belmont, ‘Pigments for Inkjet Applications’, in The Chemistry of Inkjet Inks (WORLD SCIENTIFIC, 2009), pp. 101–22 <https://doi.org/doi:10.1142/9789812818225_0006>.

[35] Printing Processes and Printing Inks, Carbon Black and Some Nitro Compounds, IARC Monographs on the Evaluation of Carcinogenic Risks to Humans, No. 65. (Lyon, 1996) <https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK424338/> [accessed 12 July 2020].