- Open today, 10 am to 5 pm.

- Parking & Directions

- Free Admission

The Evolution of the Chrysler: A Building Fit for a World-Class Collection

From the very moment of its founding in 1933 as the Norfolk Museum of Arts and Sciences, the Chrysler Museum of Art has enjoyed the enthusiastic patronage of the City of Norfolk and the unflagging support of its trustees, donors, volunteers, and members. Their steady commitment across the decades is, perhaps, most apparent in the extraordinary physical transformation of the Museum from its modest beginnings in the depths of the Great Depression to the imposing structure and ever-expanding campus that define the Chrysler today. Indeed, since 1933, the Museum building has undergone four major expansions and renovations that have increased the building’s footprint more than tenfold from an original 15,000 square feet to 220,000 today. The Chrysler has also established the Perry Glass Studio on Museum grounds. The Studio’s commitment to contemporary glassmaking serves as the creative cutting edge of the Chrysler’s famed collection of glass masterpieces just across the street.

1933-39 Norfolk Museum of Arts and Sciences

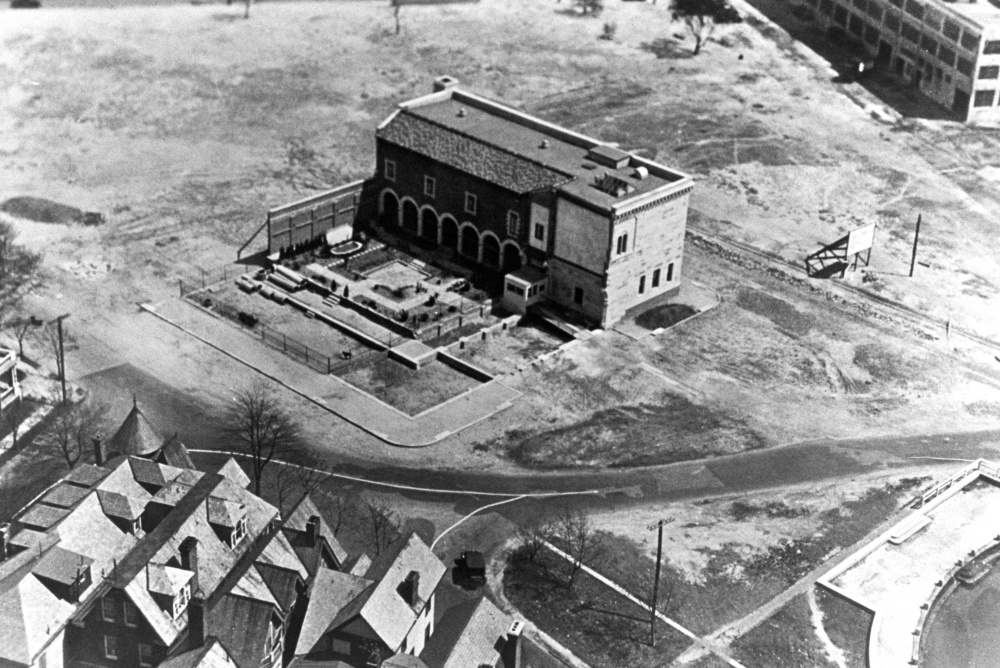

Caption on slide(s): “Aerial View – 1932; Norfolk Museum of Arts and Sciences, ca. 1930’s; 1933 Exterior, The Chrysler Museum”. Incomplete building.

With the support of the city, the Norfolk Society of Arts, and a group of prominent local individuals led by Florence Sloane, the first wing of the Norfolk Museum of Arts and Sciences opened in 1933 on The Hague inlet of the Elizabeth River in Norfolk’s fashionable Ghent neighborhood. The project architects, Peebles and Ferguson of Norfolk, envisioned a structure of restrained elegance sheathed in limestone–a two-story U-shaped edifice surrounding a courtyard and evoking the classical calm of an early Italian Renaissance palazzo. Funds, however, were scarce in the early years of the Great Depression, and only the east wing of the building was completed at the time the Museum opened. By 1939, however, additional money had been found to finish the Peebles and Ferguson design and to erect a brick wall enclosing the courtyard at the rear. The building remained essentially unchanged until the mid-1960s.

Caption on slide: “Norfolk Museum exterior, ca. 1934”. Completed front with difference in bricks due to newer construction. Scanned from 35 mm slide.

1967 — Willis Houston Memorial Wing and Tower Opens

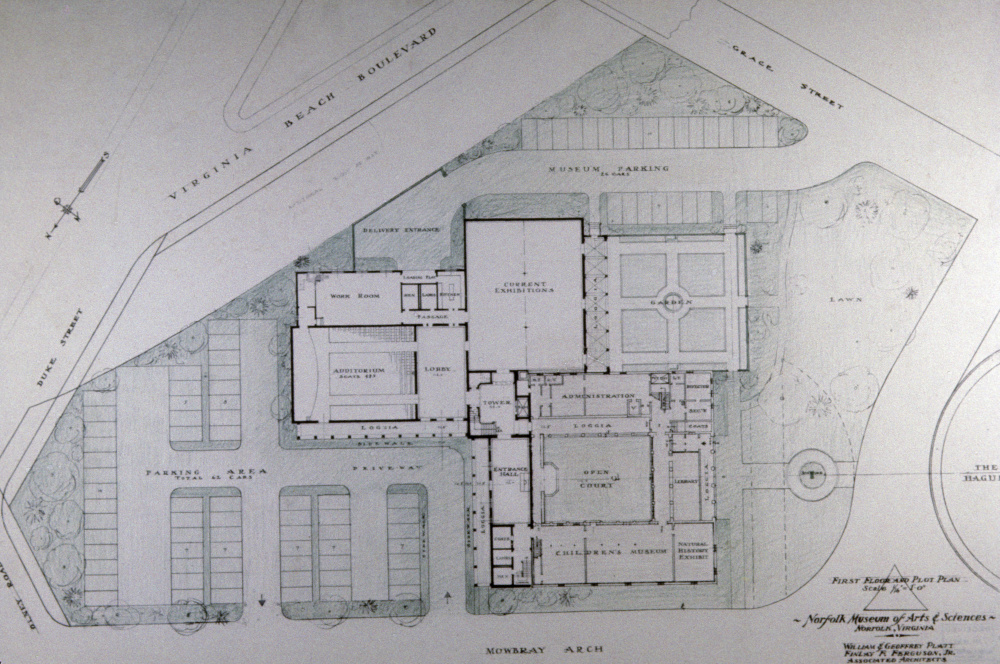

1964 Floor Plans for the Willis Houston Memorial Wing addition to Norfolk Museum of Arts and Sciences; William and Geoffrey Platt, Architects, 101 Park Avenue, New York, N.Y. Finlay F. Ferguson, Associated Architect, Norfolk, Va. E.T. Gresham, General Contractors.

By 1965, the Norfolk Museum was running out of room. It also lacked the amenities expected of a public museum in the decades after World War II as America’s leisure economy began to expand. With $600,000 bequeathed by Norfolk resident and civic leader Wilmer Willis Houston (1876–1964) and matched by the city, work began on two new wings and a mechanical tower on the Museum’s east side. The additions more than doubled the Museum’s original footprint and added an entrance foyer, gallery, loading dock, and a much-needed 300-seat theater to the Museum’s first floor. The second floor included a large exhibition hall, staff offices, and an art storage space. Opened on December 2, 1967, the new structure was named the Willis Houston Memorial Wing in memory of its principal donor.

Norfolk Museum with Houston Wing, aerial view ca. 1967, scanned from 35 mm slide.

The wing’s architects, William and Geoffrey Platt of New York City and Norfolk city architect Finlay F. Ferguson, completed the principal facade in the same Renaissance style as the 1933 building. (An anonymous donor also provided funds to create a Memorial Garden in Italianate style that still stands in front of the east wing.) But due perhaps to budget concerns, the rest of the building was finished in a more utilitarian stone and red brick design that broke with the elegance of the 1930s structure.

Norfolk Mayor Roy B. Martin, Jr. with Walter and Jean Chrysler at the opening of The Chrysler Collection Exhibition, Norfolk Museum of Arts and Sciences, 1967

The Willis Houston Wing opened with a special exhibition of Italian Renaissance and Baroque paintings belonging to the famed art collector Walter P. Chrysler, Jr. of New York and Provincetown, Massachusetts. That event would prove prophetic, for Chrysler and his wife Jean would return a mere four years later to transform the modest Norfolk Museum of Arts and Sciences into a cultural powerhouse, the Chrysler Museum of Art.

Walter Chrysler with Mayor Roy B. Martin, Jr. and other city officials, Norfolk, 1971

Few events in the history of American museums have been as momentous as Walter and Jean Chysler’s arrival in Norfolk in 1971. Walter Chrysler’s initial donation of more than 7,000 works of art all but overwhelmed the institution renamed in his honor, and his donations continued apace until his death in 1988. To accommodate the veritable flood of gifts from his collection, the institution would need to transform itself from top to bottom. It would need to grow its building, annual budget, operating endowment, and staff and expand its cultural and educational reach. Thus began a decades-long quest to create an institution worthy of the national distinction and prominence of its collection, a quest that would involve a series of sweeping renovations and expansions as the Museum worked to become the right home for its extraordinary new treasures.

Bicentennial Wing, Chrysler Museum of Art, 1976

Bicentennial Wing, Chrysler Museum of Art, 1980, Digital SLR capture by Ed Pollard on copy stand from print currently in Jean Outland Chrysler Library

The first of these expansions was an addition to the Museum’s north side that was unveiled on March 1, 1976 to herald the upcoming American Bicentennial celebration on July 4. Designed by the Norfolk architectural firm of Williams & Tazewell, it gave the Museum twenty new galleries and additional staff office space, including an elegant second-floor office for Chrysler himself. Chrysler may have felt that the Museum’s main entrance on The Hague was unwelcoming to visitors, facing as it did “away from the city.” In any event, the architects moved the main entrance to the new Bicentennial wing facing West Olney Road. A visitor parking lot was placed there as well. The most notable feature of the new wing was its stark, modernist concrete design. The addition’s blocky style, derisively described by some as High Brutalism, added another even more jarring architectural component to the Museum complex. It soon became clear that the overall building, by now a confused jumble of architectural elements, needed a grand fix. And it also needed more room.

Chrysler Museum exterior from Olney Road and Virginia Beach Blvd. Scanned from 35 mm slide.

1989 — Expanded, Hartman-Cox Chrysler Museum Opens

Chrysler Museum of Art exterior, Hague view, Fall 1988, photo by Scott Wolff, scanned from 35 mm slide.

In 1985, construction began on a major renovation and expansion that would add even more gallery and staff space to the Museum, unify and rebalance the facade in accordance with the Renaissance style of its 1933 core, and move the main entrance back to its original place facing The Hague. Overseen by Hartman-Cox Architects of Washington, D.C., the project cost $13.5 million and literally transformed the Museum, especially the exterior. A new two-story, 50,000 square-foot wing and tower were added to the Museum’s west side, which served to balance the Willis Houston Wing on the east and restore symmetry to the building’s entrance facade.

Chrysler Museum of Art, the north facade facing West Olney Rd., ca. 1989

The same symmetrical impulse determined the design of additions along the west flank and back of the Museum. The new additions were then wrapped in the same Renaissance-inspired limestone skin of the 1933 building. The former, jumbled appearance of the Museum vanished beneath a newly serene, classical face that appeared essentially timeless, as though it had all been there from day one. (Fig. 11 — Chrysler Museum of Art, Huber Court) To properly receive visitors at the newly reopened entrance on The Hague, the old, open-air courtyard just inside the door was transformed into a dramatic, enclosed, two-story atrium crowned with a massive skylight and set with a monumental limestone double staircase leading to the galleries on the second floor. The new atrium, Huber Court, would quickly become the Chrysler’s grand community living room, hosting countless Museum functions and other events.

Chrysler Museum of Art, Huber Court, 1988-89

The Hartman-Cox plan called for 50,000 square feet of new gallery and staff space and the renovation of 40,000 square feet of existing space. The Museum’s expanded footprint, now encompassing 210,000 square feet, included redesigned glass and ancient worlds galleries and a new large changing gallery on the first floor. European and American galleries were added to the second floor, where two galleries were also capped with skylights. Behind the scenes, a new loading dock was constructed and spaces added for staff offices, conservation, and art storage.

Chrysler Museum building exterior aerial view, January 1989, scanned from 35 mm slide.

Opening to the public on February 26, 1989, the Museum had, at last, achieved the stately appearance of a major arts institution, one more than worthy of its distinguished collection. (Sadly, Walter Chrysler did not survive to see the unveiling, having passed away in September 1988.) Yet, despite the building’s newly harmonized exterior and its many interior improvements, the 1989 expansion failed to address several key structural problems that would continue to hamper the institution’s daily operations. On the inside, the expansion had done little to coordinate and harmonize the divergent floor plans and mechanical systems of the earlier additions. On the plus side, thanks to the generosity of Museum trustee Linda Kaufman, the Chrysler’s theater was spectacularly refurbished and reopened in 2005 as the Kaufman Theater. But aside from this much-needed improvement, the larger Museum was still plagued by a gallery layout beset with broken sightlines and blind alleys and a hodgepodge of different, often aging, lighting and HVAC systems.

2014 Museum Expansion

Chrysler Museum of Art, 2014, photograph by Ed Pollard, Museum Photographer

The need to face those and other institutional challenges eventually inspired a 2010 Museum strategic plan that, in turn, led to a major capital campaign. The Campaign for the Future ultimately raised more than $45 million to address a range of ambitious strategic goals. Chief among them was the comprehensive expansion and renovation of the Museum’s building to include much-needed structural improvements and mechanical upgrades. Overseen by Norfolk’s H & A Architects, the expansion ultimately included a pair of two-story additions flanking the Museum entrance and capped with skylights. Sheathed in the same Renaissance-style limestone skin as the rest of building, the additions contained 10,000 square feet of new exhibition space and a newly relocated cafe and catering facility. The building’s once confusing visitor floor plan was also simplified and clarified with new pathways and vistas. The contemporary galleries were upgraded, and the aging glass and ancient worlds galleries were transformed by George Sexton Associates of Washington, D.C. Sexton also oversaw the reinstallation of the Hofheimer porcelain collection in the lobby of the Kaufman Theater. (That gallery was effectively redesigned in 2014.) Reopening on May 10, 2014, the dramatically reinvented Museum building was named in honor of Joan and Macon Brock in grateful recognition of their extraordinary generosity and decades of Museum service.

Perry Glass Studio, Chrysler Museum of Art, 2011, photograph by Ed Pollard, Museum Photographer

The campaign also envisioned establishing a long-desired, state-of-the-art glassmaking facility to complement the Museum’s extraordinary permanent glass collection. With the help of an anonymous donor and the generosity of Pat and Doug Perry, a vacant bank building adjacent to the Museum was purchased and totally redesigned, refitted, and reinvented as the Chrysler’s Perry Glass Studio. Opening on November 2, 2011, the Glass Studio was an instant hit. It not only kept the Chrysler visible and vital in the public eye while the Museum building was closed for renovation, but it quickly became one of the most creative and innovative centers of glassmaking in the United States.

Finally, the capital campaign sought to secure operating endowments for key staff positions. As was the case with the building’s expansion and the creation of the Glass Studio, the results there were astounding. Indeed, by 2014 the Museum had successfully endowed the Perry Glass Studio Manager and Director of Programming, the Carolyn and Richard Barry Curator of Glass, the Brock Curator of American Art, the Arnold and Oriana McKinnon Curator of Modern and Contemporary Art, the Irene Leache Curator of European Art, and anonymously, the Director of Museum Education. The Chrysler had already achieved a comparable coup in 2010 when an anonymous donor endowed free admission to the Museum in perpetuity.

Chrysler Museum of Art with Free Admission banner, 2009

In 2018, the Museum added the Wonder Studio, the Chrysler’s first interactive space near the front entrance adjacent to Huber Court. The space combines technology with works from the Chrysler’s collection for an experience that allows children and families to learn, explore, and experiment through the Museum’s collection and their own creativity. A generous gift from an anonymous donor served as the catalyst for the project, and the Museum worked with Bruce Wyman of USD Design│MACH Consulting and firms Upswell and Plus & Greater Than, both of Portland, Oregon, to design and fabricate the space.

Wonder Studio, 2019, photograph by Ed Pollard, Museum Photographer

The Chrysler stands today as a vibrant symbol of community commitment. Across the decades, it has expanded from a provincial museum of modest period rooms and natural history displays into an arts institution of national significance. And the story hardly ends here, for the Chrysler will surely continue to grow. Indeed, the urge to improve and expand seems baked into the Chrysler’s DNA. Whether the plans involve the building, campus, collection, exhibitions, or community reach, new projects await. We invite you to stay tuned!