- Closed today. View hours.

- Parking & Directions

- Free Admission

The History of Art in Colors – A Chromatic Tour of the Chrysler

Color has always been a deeply human, perhaps even instinctual, interest. Created approximately 17, 000 years ago, the cave paintings at Lascaux[1] are some of humanity’s earliest preserved artworks. These rare survivals show how prehistoric humans utilized several shades of earthen clay to imitate the world around them.

Horses painted on the wall of Lascaux cave

Until the digital age, artists were limited to just the physically real colorants they could acquire, often locally and at a reasonable price. Perhaps our best illustration of this is a self-portrait by the French seventeenth-century painter Nicolas de Largillière. He proudly displays his palette, conveying his profession, but maybe also asking us to consider what mastery he has created from these few mere puddles of color. It may be hard to imagine as we casually squeeze a tube of paint onto our palette, but these base materials contain a history that stretches as far back as our prehistoric ancestors painting cave walls. Through nearly every age of humanity, exploration, mining, technology, and chemistry have resulted in new pigments for artists to use. Each new generation of color presented new opportunities for artistic expression that perhaps was not possible or even conceivable before. The study of this invisible guiding hand has burgeoned into its own field known as material culture, offering a fresh perspective on the story of art history. Museums like the Chrysler now collect not only the masterworks of great painters but also the few precious surviving examples of their paint boxes and palettes. Over the next several weeks, we will explore the fascinating and often surprising story of these materials through the history of art. Join us as we tour the Chrysler’s collection through the prism of color.

Nicolas de Largillière (French, 1656–1746), The Artist in his Studio, ca. 1686, Oil on canvas, Gift of Walter P. Chrysler, Jr., 71.513

William Trost Richards (American, 1833–1905), Paint Box with Palette of William Trost Richards, ca. 1890s, Wood, Gift of Edith Ballinger Price, 94.24.68

Throughout history, fascination with color led curious intellectuals to study and understand what exactly color is. As early as 300 B.C.E., Aristotle laid down his influential theories on the relationship of color to light and dark. The first recorded color wheel was created in 1611, nearly a century before Isaac Newton published his famous one in 1704.[2] It was through centuries of studying optics, physics, chemistry, and biology (the workings of the human eye) that humanity came to its contemporary understanding of the complex phenomena of color.

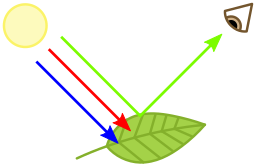

We now understand that color is fundamentally the interaction of light with physical objects and our eyes. White light contains the full spectrum of color that can be broken with a prism into every color of the rainbow. When white light encounters an object, some of these colors are absorbed while others are reflected or transmitted. The light that escapes absorption thus determines the object’s color. This is what creates the colors of pigments found in artworks. In nature, colors may be created through more complex phenomena like the scattering of this incident light that results in more unique colors. Examples of this include the iridescent blue color of a Morpho butterfly’s wings (which contains no blue pigment at all), the bright red of a sunset (made only from the Earth’s colorless atmospheric particles), and the green of one’s iris (which contains no green pigment at all as we are only capable of producing brownish melanin pigments).

“Plants are perceived as green because chlorophyll absorbs mainly the blue and red wavelength and reflects the green.” By Nefronus – Own work, CC BY-SA 4.0

For most of history, color was created with natural minerals or dyes. A pigment is a solid particle that stays suspended in a medium like acrylic or oil paint. A dye is a compound that dissolves into a medium, which may be used for coloring textiles, as ink, or to stain colorless pigment particles to make paint. In the earliest days of humanity, mineral colors were collected from the Earth’s surface as clay, a naturally smooth and finely ground material ready for application as pigment or pottery. These colors are still used today—often given the name ‘ochre’ or named for their origin as in burnt sienna (Sienna, Italy) or Indian Red (from the Indian subcontinent).

Red clay, Vietnam

As civilization formed, people found that mining deeper under the surface could yield more colorful and precious minerals like malachite (green) and cinnabar (red). These are typically soft minerals that can be readily crushed in a process that allows for the production of tiny pigment grains from a piece of raw ore. A range of techniques, including grinding, washing, floating, and sieving may be utilized to achieve the best results for each pigment. Other colors were made of plant and animal dyes. For example, madder plants produced crimson red and woad and indigo plants produced blue.

Malachite stalactites from Kasompi Mine, Katanga Province, Democratic Republic of the Congo, photo by Rob Lavinsky

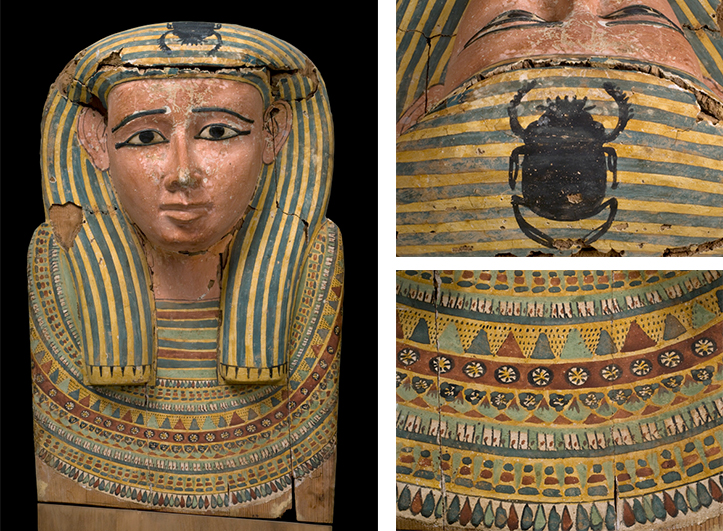

It was not long before it was realized that many of these minerals underwent a color change when merely heated. This simple technology evolved into the complex manufacture of new synthetic pigments like Egypt Blue, the earliest synthetic pigment known. The Egyptians invented their eponymous blue by at least the beginning of the Old Kingdom, 2,575 years before the common era began. The process involved heating sand, lime, and malachite until a brilliant and nearly indestructible blue was formed—with many examples surviving thousands of years in the sun of the Sahara.[3] The mining of ores also meant that other simple synthetic pigments could be synthesized using the corrosive action of solutions like white vinegar. Copper and lead were easily transformed into green verdigris and lead white.

Sarcophagus Cover, Late Period, 664–525 B.C.E., Cartonnage, gesso, and paint on wood, Gift of Walter P. Chrysler, Jr. 0.1977

Oxidation of copper – utilized in the past to make blue-green Verdigris pigments

These forms of color served the world for several centuries; artists updated their palettes as new animals, plants, and minerals were discovered. In the eighteenth century, people learned how to more purposefully manipulate the chemical matter of the world, making many new colors available to artists. It is perhaps a foreign thought to many, but art— and especially color—are the products of science and technology. Many color discoveries were serendipitous accidents produced by those experimenting with new chemistry, while others were the product of decades of intensive research and refinement. The developments of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries truly brought our world into color vision, with the synthesis of nearly every color we still use today. However, new colors like Vantablack® continue to expand our palettes, creating uniquely twenty-first-century works.

In this series, join me as we explore the stories that each color can tell us about the history of art. What does the color white reveal about the technology of paint? What was the best historical brown pigment made from, and why was it so gruesomely necessary? Why has green always posed problems for artists? Why was blue written into the contract of painters in the fifteenth century? How are we able to make our modern world so richly colorful? These and more stories will be unraveled as we tour the Chrysler collection through the spectrum of color.

–Brandon Finney, NEH Conservation Fellow

[1] E Chalmin, C Vignaud, and M Menu, ‘Palaeolithic Painting Matter: Natural or Heat-Treated Pigment?’, Applied Physics A, 79.2 (2004), 187–91 <https://doi.org/10.1007/s00339-004-2542-0>.

[2] Charles Parkhurst and Robert L Feller, ‘Who Invented the Color Wheel?’, Color Research & Application, 7.3 (1982), 217–30 <https://doi.org/10.1002/col.5080070302>.

[3] Heinz Berke, ‘The Invention of Blue and Purple Pigments in Ancient Times’, Chemical Society Reviews, 36.1 (2006), 15–30 <https://doi.org/10.1039/b606268g>.