- Closed today. View hours.

- Parking & Directions

- Free Admission

Restoring Portrait of Francesco Bollani

-Brandon Finney, National Endowment for the Arts Fellow in Conservation

Anonymous 17th century Italian artist, Portrait of a Man (Francesco Bollani), 17th century, Oil on canvas, Museum purchase, Chrysler Museum of Art, 55.38.1 (Before restoration)

The proverbial attic, even in a museum, can hold many treasures and secrets. When I first saw this portrait in storage, I could not have imagined what stories it would have to tell us. The portrait was arresting, clearly the work of an Italian seventeenth-century Old Master with great skill at painting both the human figure and the psychological presence of the mind. The subject, an elegant gentleman, dramatically flourishes a freshly opened letter. Perhaps just arriving home, he is still bundled in his heavy fur-trimmed overcoat. He appears to have hastily removed just one of his gloves in order to open his important post. With only these simple motifs, the painter had infused his portrait with the baroque drama that typified much of Italian and European art in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries.

Such an excellent work surely deserved its chance to be seen on the walls of the Chrysler, but a few glaring issues had kept this painting in storage for some time. Where the sitter’s gloved hand had once been was now a formless area of damaged brown underpaint. Several areas of old retouching had discolored. The surface appeared hazy and several areas worn. Our baroque portrait was truly broken. Furthermore, who was this man?

In the Conservation Lab for Examination

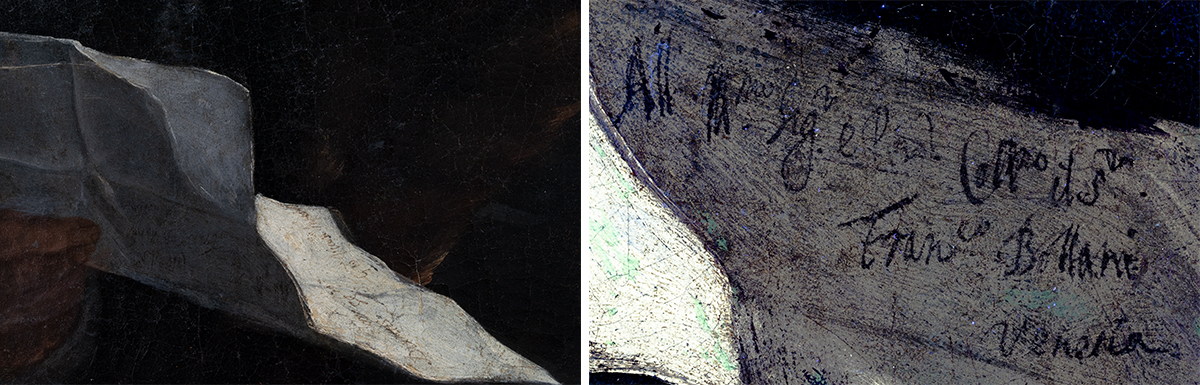

Before undertaking any conservation work, a painting is thoroughly examined and documented. During my initial examination in the lab, I was able to look very closely at the letter held by the then-unknown sitter. Just like real handwritten letters, those in paintings are often signed, leaving an explicit record of the sender and recipient. Unfortunately, the inscription in the Chrysler’s painting is largely illegible to the unaided eye and likely has been so for over a century. Auction records dating back to the nineteenth century show no name associated with the portrait. However, using ultraviolet light, a surprising find was made.

Detail of letter. Left: normal illumination. Right: the ultraviolet-induced fluorescence image is from the dark portion of the letter next to Francesco’s hand. It has been rotated and enhanced for legibility. Photography by Brandon Finney

By capturing a high-resolution digital photograph under ultraviolet lighting, the nearly illegible text became unexpectedly clear. In Italian abbreviation, the letter can be read and translated: “All’Illustrissimo Signore e Patron Collendissimo il Signor Francesco Bollani Venezia (To the most illustrious and honorable master Signor Francesco Bollani of Venice).” The sender’s name is even less clear but possibly reads “Divotissimo Servitore Giovanni Vincenzo Imp (Your most devoted servant Giovanni Vincenzo Imperiale).” Vincenzo Imperiale was an important Genoese aristocrat and politician.

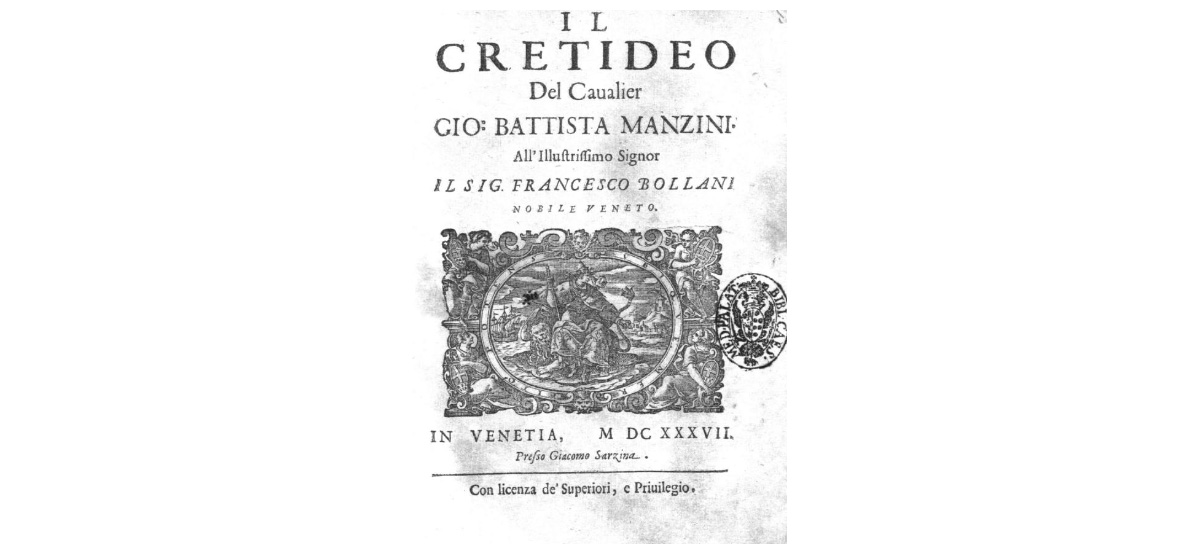

Meet Francesco

Reaching back through nearly 400 years of history, we can learn a great deal about our mystery man. Francesco (ca. 1608– ca. 1668) appears to have been an important man of Venetian aristocratic society. He is described as “a man of letters,” passionate for the arts of Italian literature and poetry. Several sources indicate Francesco’s wide sphere of artistic influence, including an introduction to the Italian novel Il Cretideo Del Caulier he penned for an edition published in Venice (1637), as well as a series of lifelong letters exchanged with the poet and musician Bellerofonte Castaldi. Sources further indicate that Francesco was close friends with the renowned composer Claudio Monteverdi, pioneer of the then-new genre of opera. This contextual evidence suggests it was possible Francesco knew the powerful nobleman Giovanni Vincenzo Imperiale through a mutual love of the arts, himself also an accomplished writer and poet.

A dedication by Francesco Bollani for the Italian novel Il Cretideo Del Caulier. Published in Venice 1637. Image courtesy of Internet Culturale and the Biblioteca Nazionale Centrale, Florence.

Left: UV Image of Francesco’s letter, from the lighter portion. Right: Sir Anthony van Dyck (Flemish, 1599–1641), Giovanni Vincenzo Imperiale, 1626, Oil on canvas, NGA Washington, 1942.9.89. Image courtesy of the NGA, Washington.

The Life of an Old Master Painting

With my research on Francesco completed, I turned back to the other areas of his portrait that needed critical attention from conservation. Francesco’s hand—while insinuated by the well-modeled red cuff—rapidly fell away into a hoof-like, formless mass of brown underpaint lacking any trace of fingers. It certainly wasn’t the artist’s intention; how did the picture come to look like this?

Left: Portrait of a Man (Francesco Bollani) before treatment Right: Detail of damaged hand. Photography by Brandon Finney

Visitors are often surprised to learn that paintings are both fragile and “living” objects. Many paintings have only survived because many hands have intervened on them over the centuries and their owners wanted them to look appealing. Before the advent of modern conservation, paintings were cleaned of discolored varnish with harsh solvents that often caused some degree of damage to the oil paint below. It was common practice that damaged areas would simply be touched-up or extensively repainted with new oil paint to match that of the original painting. Unfortunately, within a decade, oil paint will undergo a subtle color shift that causes this retouching to no longer match that of the original painting. The change incites further cleaning that could lead to further damage. A badly damaged area of original paint may also be mistaken for poor retouching and scrubbed down even further. In the case of Francesco—a once fully modeled, gloved hand was likely lost to this cycle of cleaning damage—leaving a distracting void in an otherwise dynamic composition. In discussion with Lloyd DeWitt, PhD, the Chrysler’s Chief Curator and Irene Leache Curator of European Art, and Mark Lewis, the Chrysler’s conservator, it was agreed that reconstruction of this missing hand would be beneficial to the picture.

A Search for Inspiration

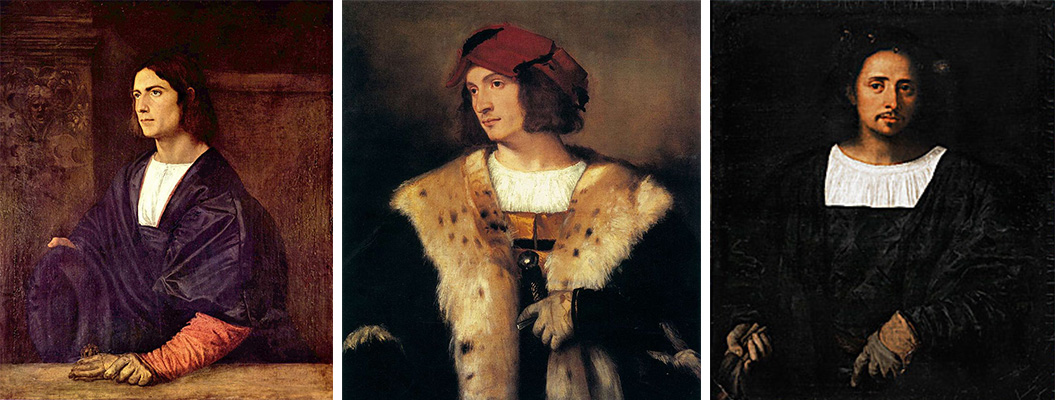

While I likely never will know what Francesco’s original hand looked like, I knew the picture had significant ties to the artistic culture of seventeenth-century Venice. Studying the touchstone portraits of Venetian art in this period reveals how artists composed and painted their subjects. Although Titian worked during the century predating our portrait, as one of the uncontested masters of painting, he continued to heavily influence Venetian art in the seventeenth century. The great painter’s early sixteenth-century portraits are filled with figures flashing gloved hands. These costly accessories were signifiers of wealth, and portraits like these were status symbols that would not be out of place in the grand palazzos the Bollani family owned.

Left to Right:

Titian (Italian, 1488–1576), Portrait of a Young Man, 1515–1520, Oil on canvas, The National Gallery of London, Image courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

Titian (Italian, 1488–1576), Man with a Red Cap, ca. 1510, Oil on canvas, The Frick Collection, Image courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

Titian (Italian, 1488–1576), Portrait of a Man, 1517–1520, Oil on canvas Musée Fesch. Image courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.

Left: Titian (Italian, 1488–1576) Man with a Glove, ca. 1520, Oil on canvas, Musée du Louvre, Image courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

Right: Anonymous 17th century Italian artist, Portrait of a Man (Francesco Bollani), 17th century, Oil on canvas, Museum purchase, Chrysler Museum of Art, 55.38.1

Titian’s Man with a Glove (Louvre) has the most similarities to the portrait of Francesco. A bent elbow and foreshortened forearm lead to a ruffled cuffed, hinged wrist, and hanging hand. Both hold a second glove sideways, indicated in the Chrysler’s portrait by the remains of a red cuff. I had found a plausible reference for Francesco’s dynamic pose—a take on the status symbols and highbrow artistic taste represented by Titian’s sixteenth-century portraits.

Restoring Francesco

Even with such a strong compositional resemblance, I needed to tune the forms of Titian’s hand to the unique portrait of Francesco. In Photoshop, I determined the scale and angle of the hand and glove. This also allowed for a digital reconstruction to be consulted and approved before continuing the process. Then using retouching paint, it was necessary for me to practice how the more artistic aspects like brush strokes, blending, and shading could be matched to the original surface of the work. Several mock-ups were made in differing materials until I felt confident that I could carry out the reconstruction on the original painting.

Left: Photo-composite image. Glove from Titian’s work digitally added to our portrait to fine tune and test solution before final restoration is applied to the actual painting. Right: Mock-up of reconstruction. Photography by Brandon Finney

It was only then—with extensive research, planning, input, approval, and practice— that the actual reconstruction could finally proceed. This was carried out with contemporary, conservation-grade materials. Unlike the oil paint used in the past to restore works, the resin paints used now are engineered to stay colorfast and readily reversible without causing harm to the paint surface. Even with all of this careful planning, any retouchings applied to the surface of the painting should remain reversible in case they age poorly or a future conservator deems them inappropriate–perhaps we find an etching made after the painting as it truly was 400 years ago.

Detail, glove before and after restoration. Photography by Brandon Finney

Every Old Master painting has some degree of retouching. While the reconstruction of Francesco’s hand is a bold example of the limits of restoration, the aim of this process is not to make the artwork look new or perfect. Instead, this project allows visitors to appreciate the painting as the artist intended. Our newly restored piece now showcases the artist’s great skill in rendering the human form and once again conveys the small baroque drama he has scripted for our entertainment. Francesco signals his haste to open the letter by only taking the time to remove a single glove. Perhaps Signor Vincenzo Imperiale has sent him a new poem.

Final, before and after restoration.

Anonymous 17th century Italian artist, Portrait of a Man (Francesco Bollani), 17th century, Oil on canvas, Museum purchase, Chrysler Museum of Art, 55.38.1

I would like to thank Dr. Valeria De Lucca, Associate Professor and Head of Internationalisation in Music, University of Southampton for help with deciphering and translating the inscription in this portrait.