- Closed today. View hours.

- Parking & Directions

- Free Admission

Restoring Edward Mitchell Bannister’s Migration at Sunset

–Jennifer Myers, National Endowment for the Humanities Conservation Fellow

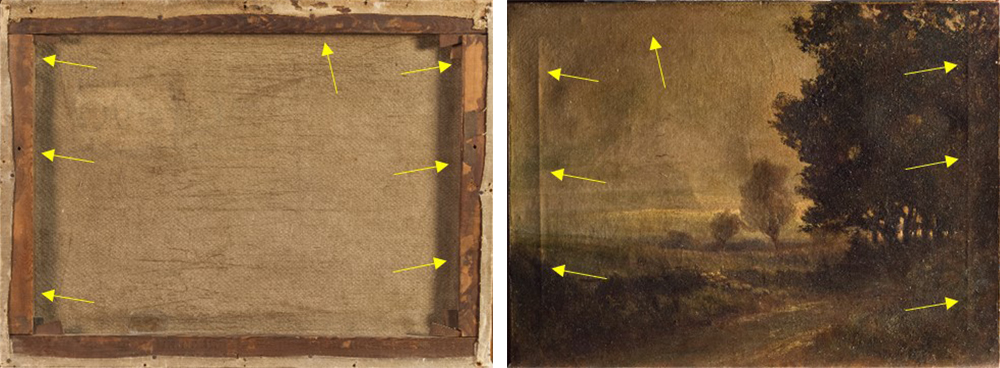

(left) Before treatment image. (right) After treatment image. Edward Mitchell Bannister (American (born Canada), 1828-1901), Migration at Sunset, ca. late 1870s-early 1880s, Oil on canvas, Museum purchase, 2020.22, Photos by Ed Pollard

Edward Mitchell Bannister, one of the most successful African American artists of the late nineteenth century, left us with a rich assortment of paintings and sketches depicting various subjects, mostly of local landscapes. The Smithsonian American Art Museum collected and cared for a large number of his works, but still, many are scattered around the United States and beyond. As interest in art made by African Americans grows, many of Bannister’s paintings have resurfaced in the last few decades, showing up more frequently on the market and in exhibitions. Last year, the Chrysler Museum purchased Migration at Sunset, a work Bannister painted between the late 1870s and early 1880s. When the work arrived at the Chrysler, it didn’t look its best. After transformative conservation treatment, the artwork is now at home in the Chrysler’s galleries.

PAINTINGS ARE COMPOSITES

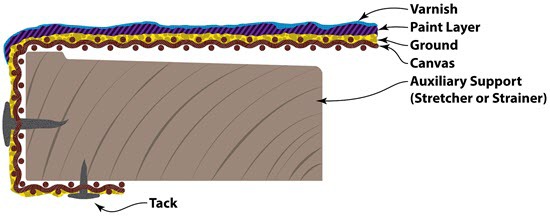

Typical cross-section of a stretched painting on canvas. Image credit © Government of Canada, Canadian Conservation Institute. CCI 130103-0002.

Conservators seek to understand materials that an artist has used to make an artwork. That knowledge allows for more informed decision-making to provide safe storage, transport, and display for a painting. This information also helps conservators repair a damaged artwork and enables art historians to place a work within a historical or geographical context. Sometimes, we use specialized tools to help us see what the naked eye cannot. We examine the structure and layers, including the supports, preparation layers, paint, and any surface coatings present. Paintings are composite objects, which means they are made from a variety of unrelated natural or man-made materials that are smooshed together into a sandwich that is intended to function as one solid object.

Unfortunately, these mixed materials, combined with variable environmental conditions and practices of human care or handling, culminate in an infinite range of potential reactions within or between layers, resulting in condition issues. Sometimes, these issues are detrimental to viewing and appreciating the artist’s intention. They may affect the structural integrity of an artwork, and the painting may be at risk of losing imagery or falling apart. When the Chrysler acquired Bannister’s Migration at Sunset, it was a bit drab and dark with some distortions in the canvas support, but the Museum’s conservator, Mark Lewis, felt strongly there was great potential to preserve the painting and reveal the artist’s intentions through a restoration campaign.

MATERIALS, TECHNIQUES, AND CONDITION

How did Bannister make this painting? We can learn so much by just looking! The texture of the canvas comes through the paint on the front, but on the reverse, specific characteristics of the fabric are clearer. We can also see that the canvas is not glued to a board but tensioned and tacked to a wooden stretcher. This is an interior frame that has slightly adjustable dimensions. Being under tension over time, the fabric naturally stretched, leaving it slack and loose and causing bulges in the painting toward the bottom as gravity acted upon it.

(left) Reverse image of the painting showing the canvas and original wooden stretcher. (right) Front image taken using strong directional light (raking light) to show the stretcher creases (marked with yellow arrows). Photos by Jennifer Myers

One important functional component of a proper stretcher is to have a “lift “in the profile of the wood toward the outside perimeter of the image (see the cross-section diagram above). This allows the stretched fabric to be held away from the wood. If there is not enough of this lift, damaging acids from the wood may be transferred to the fabric, as well as cause the canvas to make contact with and conform to the inner wood edge. This results in a crease in the canvas and cracked paint. Migration at Sunset suffers from these often-permanent creases, indicated with arrows in the above image on the right where strong light and shadow highlight raised areas.

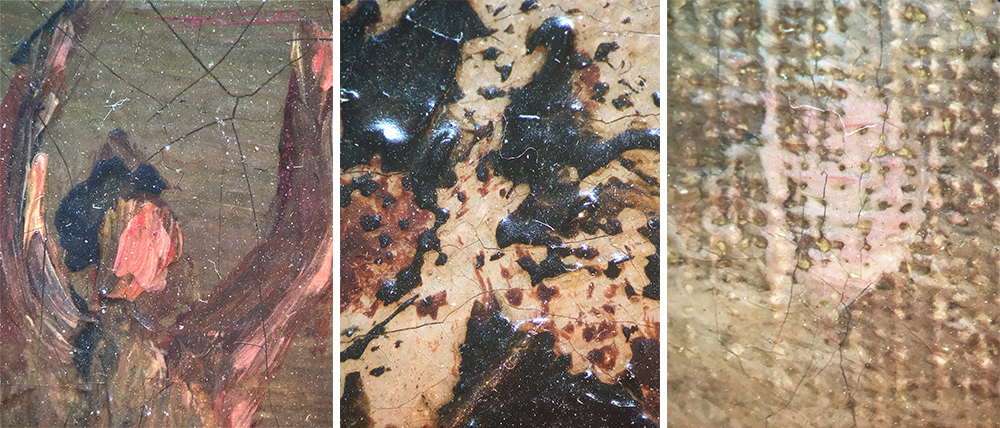

(left) Detail of figure displaying swirled wet-into-wet brush strokes. (center) Detail exhibiting three different colors of paint layered after the underneath color has dried, showing crisp edges and no swirled paint. (right) Detail of an abraded area of the painting where the tops of the fabric have been exposed when the paint has been worn away. Photos by Jennifer Myers.

The painting’s fabric is commercially primed linen, prepared for painting before purchase. It was a popular option for artists working both in the nineteenth century and today. Bannister used multiple techniques, including painting wet-into-wet, where he built the painting with brush strokes, mixing colors together directly on the painting. Additionally, he painted some areas in stages, allowing one layer to dry before adding another. We can see this in his handling of the dark tree leaves on the right side of the painting. Unfortunately, many areas of paint were skinned or abraded during the painting’s life, possibly when someone tried to clean it in the past. This left the tops of many of the canvas threads exposed as the paint wore away.

Bannister’s palette for Migration at Sunset contained many rich colors. Unfortunately, this palette and many details of the painting were obscured by a very thick and discolored varnish, which was added during a previous restoration. This coating probably looked great when it was first applied, giving saturation and depth to the painting, but the natural resin varnish became dark and cloudy over time, altering the appearance of the colors hiding underneath, particularly when comparing the painting to others by the artist.

RESTORATION

After careful examination, documentation, and cleaning tests, we decided on a course of treatment for this painting to address these issues that obscured the artist’s intent. Bannister likely did not want his colors to be viewed behind a thick yellow veil, nor have a painting with a loose, creased, and undulating canvas support. Conservation and curatorial experts at the Museum developed three major goals for conservation. We sought to: 1) properly support and re-tension the canvas, 2) remove the disfiguring surface coating, and 3) retouch areas of the painting that had become worn and damaged.

(left) The original stretcher after it was modified to add a lift, ensuring the canvas will not rest on the wooden bars once restretched. Photo by Jennifer Myers (right) Jennifer Myers using canvas pliers to tension and attach the painting to the modified stretcher, affixing the edges in place with pushpins, followed by staples. Photo by Mark Lewis

The loose and creased canvas would benefit from overall relaxation, but we first needed to carefully remove the painting from its wooden support. This required removing the tacks, securing the canvas in place, and separating the stretcher from the painting. The wooden stretcher was modified to better support the painting instead of replacing the original with a new one. An addition of wood was precisely fashioned and added along the outside edge to create a proper lift. This allowed important original parts of the painting to remain together, as the stretcher was in good condition otherwise. Next, wide strips of thin and flexible synthetic fabric were attached to the reverse of the painting using a removable adhesive film. This gave us something to hold on to when re-stretching the canvas around the modified wooden stretcher, as the 140-year-old original canvas edges were worn and brittle and would not withstand this re-tensioning process.

(left) Image of the painting taken during its treatment when the yellowed varnish was about halfway removed. (right) Jennifer Myers removing the varnish from the painting in the studio. Photos by Jennifer Myers.

The thick yellow veil was removed using a combination of solvents delivered in a gelled form to the surface coating. This coating had become very difficult to remove over time, a likely result of a drying oil added to its formulation. Using gelled solvents allowed us to have more control over their strength and how long they interacted with the surface. This method is slow, as only small areas can be worked at a time, but the results were quite satisfactory. The painting was brought further back to life when its colors were saturated with a new, easily removable, and non-yellowing conservation-grade varnish. Bannister’s skillful use of color to convey the atmosphere was now visible to a very surprised and delighted audience here at the Museum. His subtle strokes of diffuse and cool tones create a true sense of distance. Elements of his composition became more prominent as he directs the viewer through the painting in a spiral path reminiscent of the Golden Ratio. The quiet mood of the sunset at the end of a long day can now be experienced in a renewed way!

(left) The painting after a conservation-grade varnish has been added, increasing the saturation of the many subtle dark colors in the trees and foreground. Photo by Jennifer Myers (right) After treatment image following retouching and framing. Photo by Ed Pollard.

Visual harmony was achieved by bridging well-preserved areas with those that had lost their original brush strokes due to abrasion or the natural process of some colors of oil paint losing their opacity over time. To carry out this retouching, we used paint that contains similar pigments to the original painting but is made with a synthetic, non-yellowing binder. This makes all of the retouching very easily reversible should there be a desire to remove it later.

As the painting came into our collection without an accompanying frame, we acquired a nineteenth-century, gilded frame for its display. The freshly revealed tonal atmospheric qualities Edward Mitchell Bannister so carefully incorporated into his beautiful painting are a treat to the mind and the senses and a nod to the influences that shaped his evolving style.

Edward Mitchell Bannister (American (born Canada), 1828–1901), Migration at Sunset, ca. 1880, Oil on canvas, Museum purchase, 2020.22