- Open today, 10 am to 5 pm.

- Parking & Directions

- Free Admission

Pinocchio’s Original Adventures

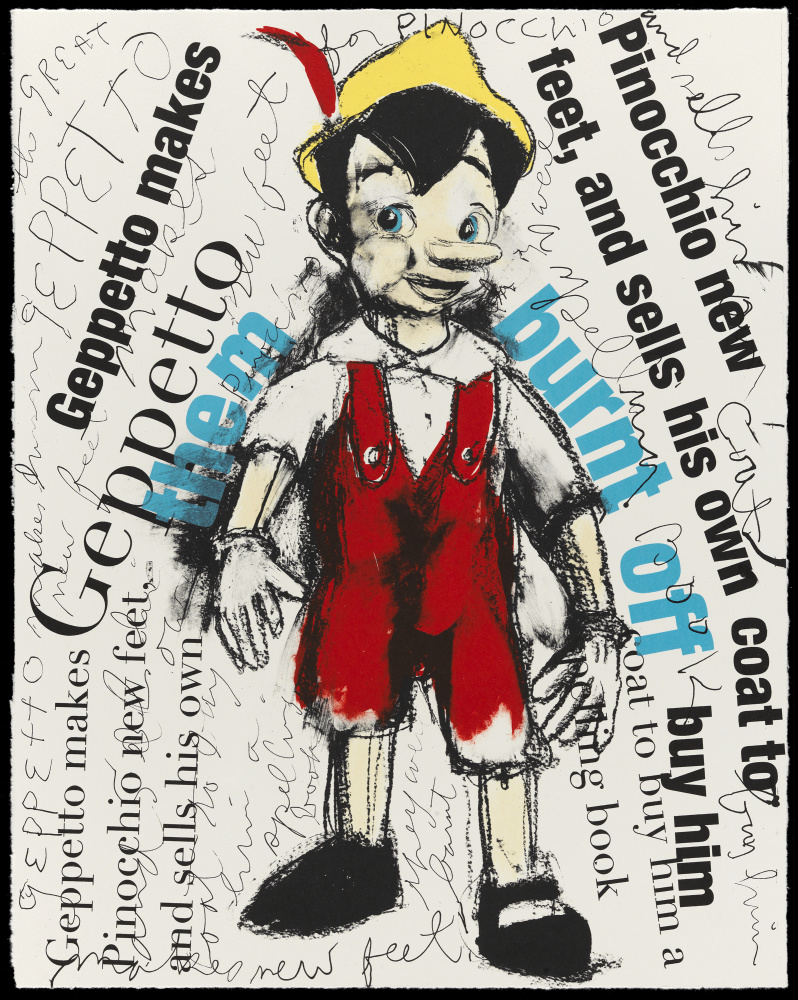

Jim Dine (American b. 1935), Pinocchio (portfolio), 2006

Pinocchio turns 80 this year! Well, at least the Pinocchio you probably know and love. In 1940, the wooden puppet of Disney fame made his debut on the big screen. Multimedia artist Jim Dine remembers it well. “I was six years old when I saw the Disney film. It was really frightening,” Dine said. “His story resonates with me as a person who’s been a boy. It is also a wonderful metaphor for the idea of making art; it’s alchemical. It’s an incredibly direct way of speaking about the act.”[1]

Before his Disney debut, Pinocchio had a pretty wild life. Through forty-four lithographs by Dine, the Chrysler shares the story of the original Pinocchio—the nineteenth-century creation of Carlo Collodi. The lithographs, a gift from Museum supporters Charlotte and Gil Minor, include images as well as text from Collodi’s original, much darker tale that found Pinocchio breaking promises and facing life-threatening dangers.

Gallery View: Jim Dine’s Pinocchio

The Italian writer and journalist introduced the rambunctious fella in Collodi’s Le avventure di Pinocchio: Storia di un burattino (The Adventures of Pinocchio: Story of a Puppet). The tale was published in the serial newspaper Il Giornale per i bambini (Journal for Children) in 1881.[2] Collodi initially wrote fifteen chapters of the story, with Pinocchio dying a violent death by hanging. However, readers loved the figure so much that Collodi resurrected Pinocchio and went on to write twenty-one more tales, finally ending the serial in spring 1883. In that same year, a publisher compiled all the stories and bound them into one volume titled Le avventure di Pinocchio (The Adventures of Pinocchio) with illustrations by Enrico Mazzanti.[3]

As an established artist, Dine incorporated Pinocchio into his practice because he felt he was similar to the character of Geppetto, the man who made Pinocchio. “Every artist is an alchemist – as I understand the alchemical act. That’s what the story of Pinocchio is about: a talking stick that Geppetto carved into a boy that became alive. That was the part of the story that got me, ever since I saw the Walt Disney movie when I was a little boy,”[4] Dine said.

Jim Dine (American b. 1935), Pinocchio (portfolio), 2006

The recognizable character has recurred in Dine’s works for over twenty years. In a 1997 drawing, the artist depicts the adventurous Pinocchio sitting on the back of Death, who is walking in an indeterminate space. This particularly grim vision of the popular character seems to reference the artist’s childhood fear of the film, which highly contrasts the bright colors and songs presented by Disney. In the later 2006 lithographs, the artist sometimes combines depictions of Pinocchio with partially obscured text describing the puppet’s adventures, some quite macabre. The images are filled with bright colors of yellow, red, teal, and orange yet the scenes present a tale of an obnoxious young boy who encounters many dangerous situations before finally learning humility and redemption. Though the story dates back more than a century, Dine’s contemporary creativity exudes from his interpretations, introducing visitors to a different version of a character they think they know.

Gallery View: Jim Dine’s Pinocchio

Dine has been working in various forms of printmaking since the 1970s. For him, the medium is just as important as painting, sculpture, and drawing; when he makes a print, he uses all the other approaches. One of the perks of printmaking is the ability to print multiple impressions of the same design from one source. However, Dine rarely makes prints that are identical. Instead, he makes subtle changes to each one by hand painting it or drawing on it to create a unique work every time. Without creating an entirely new work, he gets new results with each print. The differences make the work more exciting. [5] Presumably, there are slight variations in each of Dine’s Pinocchio prints, demonstrating his skill in lithography and giving each collector their own unique work.

While Dine focused on lithography for his images of Pinocchio, printmaking encompasses numerous methods. Some of these other approaches – engraving, woodcut, and etching – can be found in the Chrysler’s Edvard Munch and the Cycle of Life: Prints from the National Gallery of Art. Tour the exhibition online, and be sure to visit it when the Museum reopens as the closing date has been extended. Want to learn more and experiment with various methods of printmaking? Check out the Museum of Modern Art’s activity What Is a Print?

–Kimberli Gant, PhD, McKinnon Curator of Modern & Contemporary Art

[1] Paul Gray, “Jim Dine of Pinocchio,” in Jim Dine: Pinocchio as I Knew Him, Richard Gray Gallery (Chicago: Richard Gray Gallery, 2005), 1.

[2] John Hopper and Anna Kraczyna, “The Truth About Pinocchio’s Nose,” The New York Times, May 10, 2019, https://www.nytimes.com/2019/05/10/books/review/pinocchio-carlo-collodi-lorenzini.html

[3] Hopper and Kraczyna, “Pinocchio.”

[4] Joseph Ruzicka, ‘“to invent what you are”: Jim Dine and Printmaking,’ Art on Paper, 6, no. 5 (May-June 2002): 66.

[5] Ruzicka, “to invent what you are,” 64.