- Open today, 10 am to 5 pm.

- Parking & Directions

- Free Admission

Object of the Week: Sonya Clark’s Octoroon

This year, the Chrysler added Sonya Clark’s Octoroon to the permanent collection. Not only does the purchase enhance the Museum’s holdings of fiber works, but it also helps meet the Chrysler’s goal of acquiring more pieces by local and regional artists. Clark is from Washington, D.C. and lived in Richmond, Virginia, where she was the Chair of Craft/Material Studies at Virginia Commonwealth University until 2017. She is now on the faculty of Amherst College.

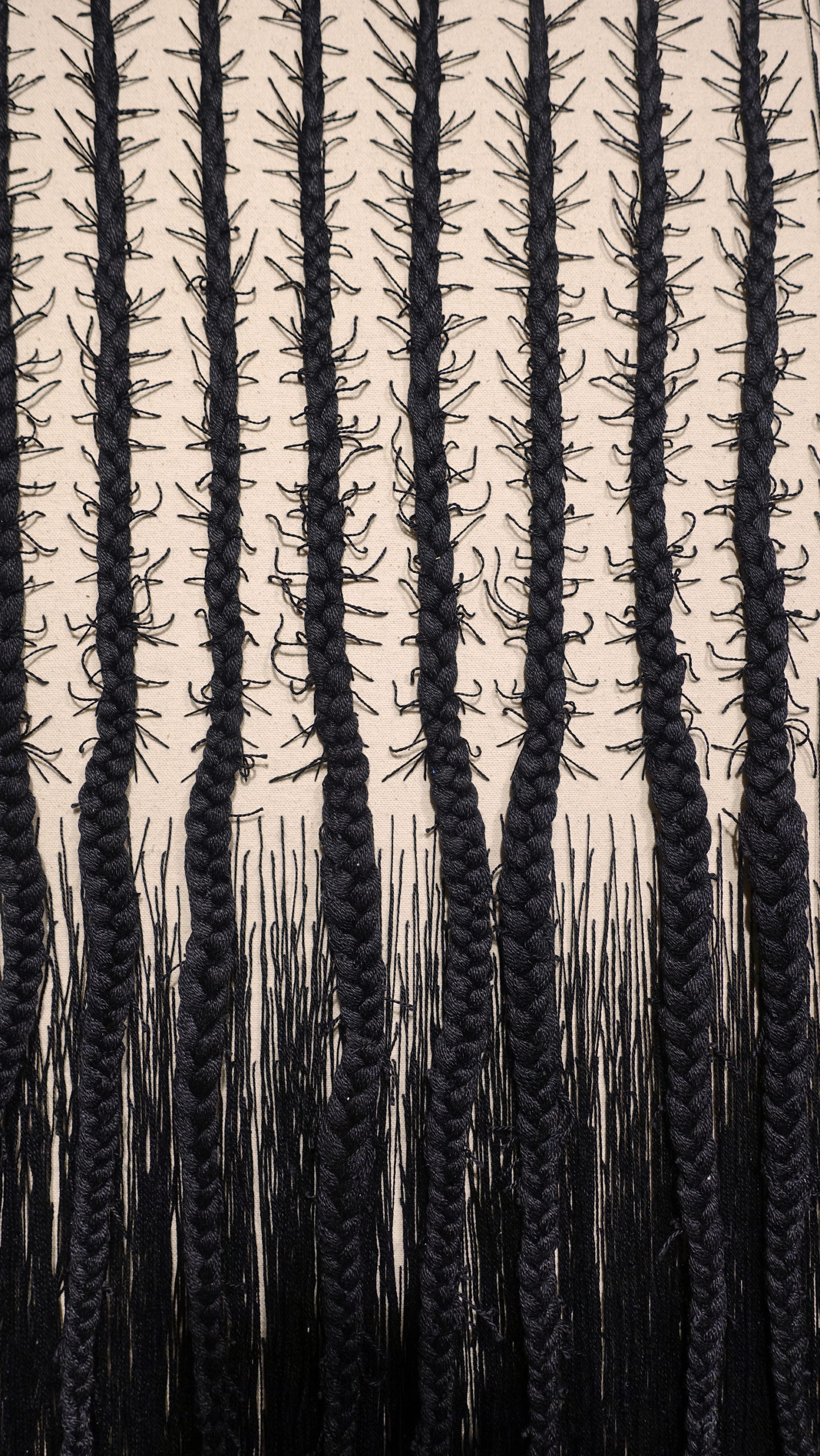

The title of the work, Octoroon, refers to the legacy of the U.S. racial classification system in the nineteenth century under Jim Crow laws. The laws stated that any individual who had one African American great-grandfather was classified as African American, no matter how that individual looked. The artist has one Scottish great-grandmother but would have never been considered Scottish as the reverse racial classifications did not exist. In the twentieth century, the definition of an octoroon was solidified into law in certain southern states as the “one-drop” rule. Thus, an octoroon was one-eighth African American. Clark’s work is gridded into eighths, giving a physical manifestation of this societal law.

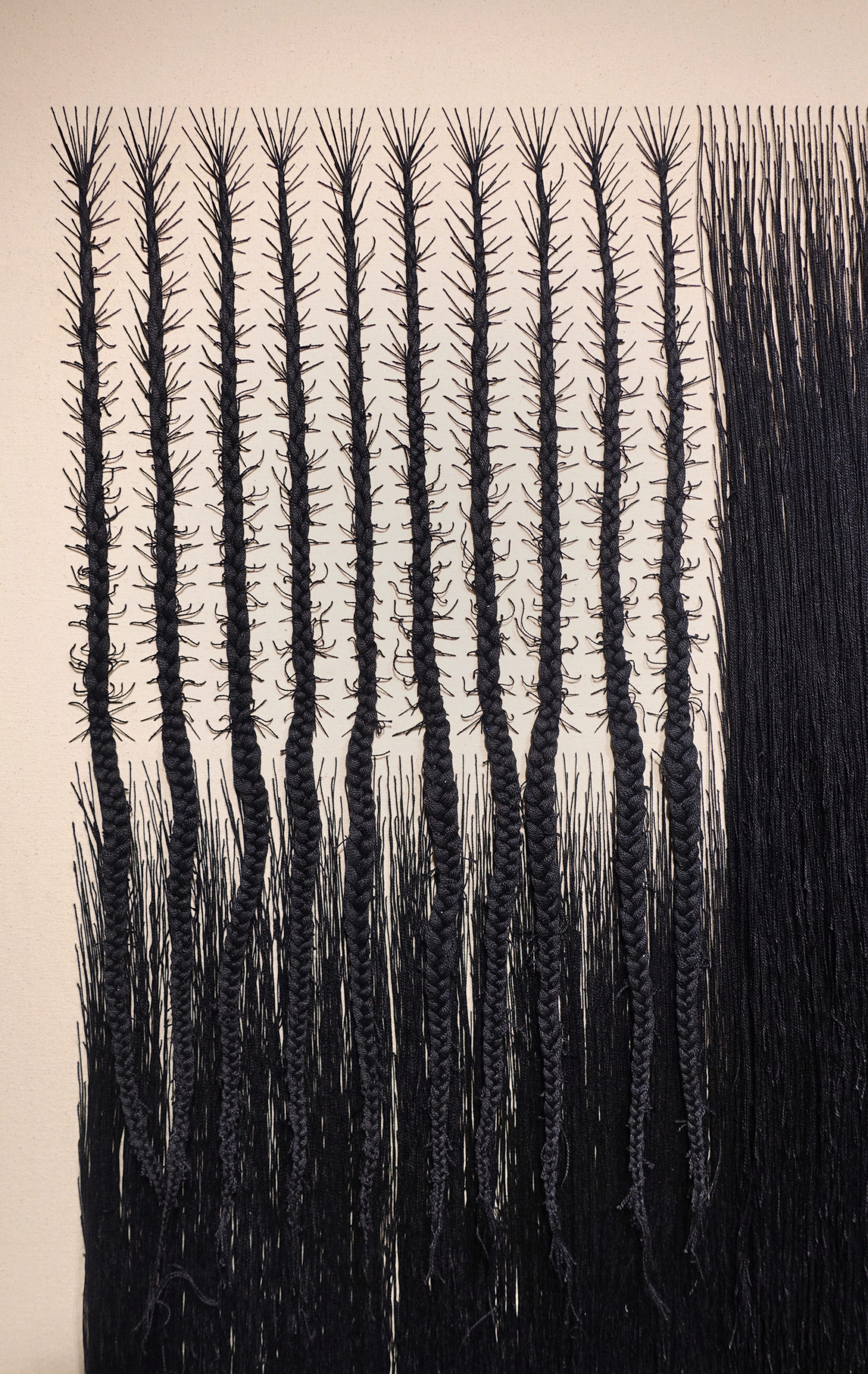

Sonya Clark (American, b. 1967), Octoroon, 2018, Canvas and thread, Chrysler Museum of Art, 2020.4, Image courtesy of the artist and Lisa Sette Gallery

Octoroon is Clark’s depiction of the United States flag. She stitched the bare canvas with threads and braided a section in a cornrows style while leaving other threads hanging loose off the canvas. The seven-by-three-foot work is a large piece that hangs vertically. It is relatively close to one of the standard dimensions of the U.S. flag, which is six-by-ten feet, albeit thinner.

Octoroon, a term now considered antiquated and discriminatory, was also affiliated with a genre of books and plays within pre-Civil War fiction. The “tragic octoroon” was traditionally depicted as a young female raised by her Caucasian father, unaware that she was an enslaved person because of her light skin color and European features. Her world perception would shift when, at her father’s death, she was sold as property. She usually died by suicide or other heartrending means. The character was a trope used by abolitionists in their fight against slavery.

Clark interweaves the legacy of craft, American history, and race to develop mixed media works that celebrate blackness and womanhood and address past and present racial tensions within society. She developed an appreciation for handmade objects and the importance of craft traditions within art from her maternal grandmother, who was a tailor. Because objects are embedded with meaning and history, the artist believes they hold power that can be presented or rethought once those items become a part of an artwork.

Sonya Clark, Photograph by Diego Valdez

Clark’s practice involves referencing personal histories, including her own. She uses fiber to draw attention to her hair, highlighting how African American women’s hair has been and continues to be a sociopolitical issue. By incorporating cornrow braids into the work, she suggests how certain styles are linked to human labor (i.e rows of corn/cornrows). In addition, certain styles such as cornrows are not considered “tidy” or “professional” because they don’t align with Eurocentric notions of beauty yet are often appropriated by non-black communities. Schools and businesses have been able to ban students or not hire individuals because of their hairstyles. However, there are small signs of changing perceptions. In 2019, several cities and states passed laws banning any discrimination towards African American hairstyles.

The artist’s images also address the role of women’s hair in various communities more broadly, as certain hairstyles signified a girl’s transition into womanhood and marriageability. Cutting the hair short was used to humiliate women who did not conform. Hair is formidable as a distinguishing feature and a way to represent oneself to the world.

Octoroon continues Clark’s interest in hair politics, though she uses thread instead of real or fake hair. The artwork blends American history with contemporary society. The Chrysler is thrilled to add Clark’s work to the growing collection of fiber works in the collection by artists Ebony Patterson, Faig Ahmed, Alexander Calder, Sophie Arp, and Loretta Pettway. Her work also adds to the increasing number of women and artists of color in the permanent collection.

-Kimberli Gant, PhD, McKinnon Curator of Modern & Contemporary Art