- Closed today. View hours.

- Parking & Directions

- Free Admission

Object of the Week: Fourth of July

Roy DeCarava (American, 1919–2009), Fourth of July, 1979, printed 1991, Photogravure, Museum purchase, in memory of Alice R. and Sol B. Frank, ©1990 Roy DeCarava, 2002.15.9

On the Fourth of July, photographers throughout the country point their cameras up to fireworks illuminating the sky. Not so with photographer Roy DeCarava, who chose to focus instead on the beautiful brilliance of the people gathered in this dim clearing in Prospect Park, Brooklyn in 1979.

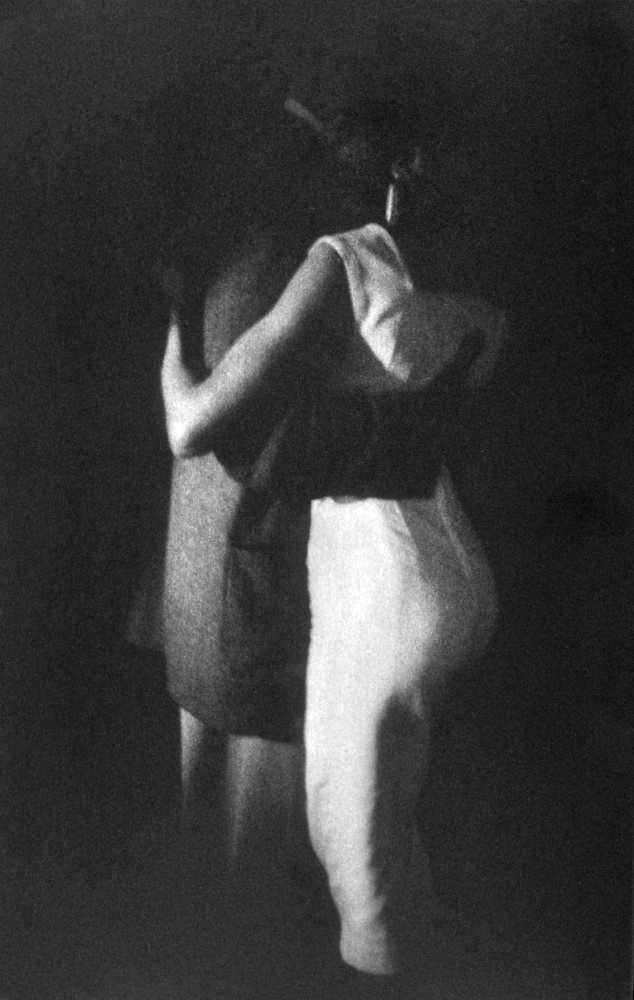

DeCarava sought to underscore shadow and uncertainty in his work, rather than lightening it out. Instead of bumping up the contrast to add definition and clarity, he allowed darkness to blossom within his scenes, simultaneously emphasizing mystery and beauty. The lightest elements—a picnic blanket and some people’s clothing—never appear brilliantly white. The darkest objects—a woman’s dress and a thicket of trees—never go to deep black. Instead, DeCarava offers an array of dark gray tones that are vivid, rich, and absorbing and yet never fully available to our eyes. The child in the foreground looks back at the camera, but his expression is almost impossible to make out, indiscernible to the photographer and to our prying eyes, but no less present, engaged, and full of life.

Born in New York in 1919, DeCarava experienced the flourishing creativity of the Harlem Renaissance as a child and came of age as an artist himself during the Depression by studying at Cooper Union and the Harlem Community Art Center. He first picked up a camera to document his paintings, but he quickly turned it to the everyday beauty of his neighborhood and the people who lived there. In 1952, DeCarava became the first African American photographer to receive a Guggenheim Fellowship. With the support of the fellowship, the photographer’s ongoing project found form in The Sweet Flypaper of Life, the photobook he produced with poet Langston Hughes.

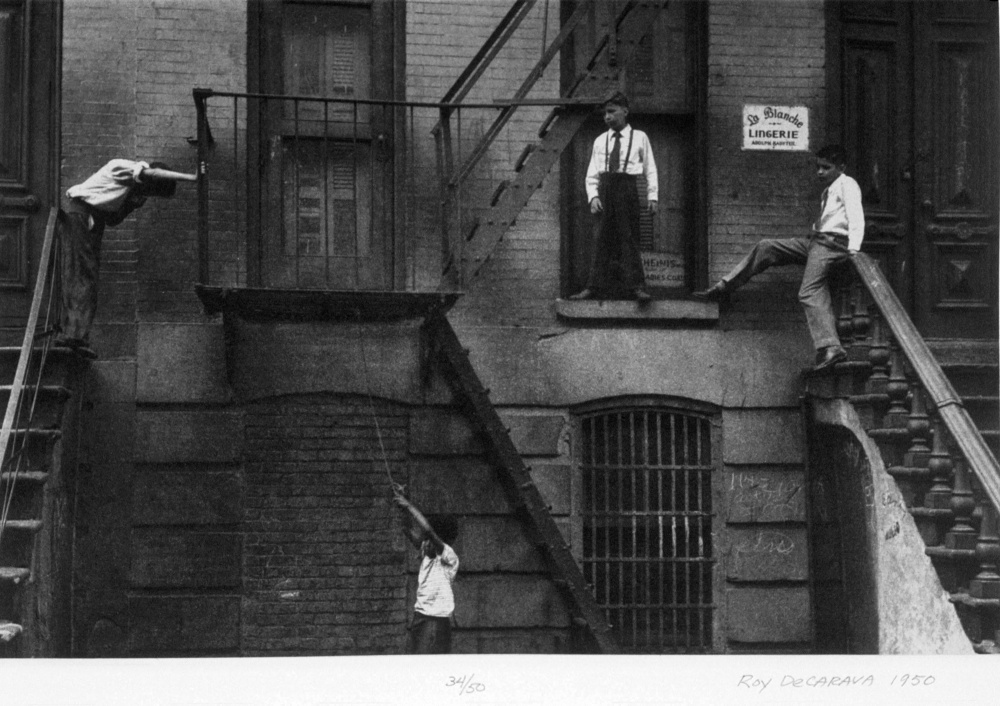

Roy DeCarava (American, 1919–2009), Lingerie, 1950, printed 1991, Photogravure, Museum purchase, in memory of Alice R. and Sol B. Frank, ©1990 Roy DeCarava, 2002.15.2

Published in 1955, the book at first appears to be a straightforward documentary about everyday life in Harlem. People go about their business, cool off in the spray of an open fire hydrant, sing at the kitchen table, celebrate graduations, and simply hang out while enjoying the company of neighbors. Yet as the poetic narrative unfolds, the book becomes an especially life-affirming take on the beauty and texture of black life, even defiantly so as it contrasts this beauty with the challenges facing the community and the misperception of it from the world outside. As the fictionalized narrator, the elder Sister Mary Bradley says, “I done got my feet caught in the sweet flypaper of life, and I’ll be dogged if I want to get loose,” assertively laying claim to the beautiful yet imperfect world around her. Hughes later put it in somewhat different terms: “We’ve had so many books about how bad life is; maybe it’s time to have one showing how good it is.”

DeCarava applied Hughes’s message to the medium of photography itself. An expert at fine-tuning black and white film and gelatin silver paper, DeCarava confronted the white bias inherent in a medium calibrated to favor light skin. The idea that film and photo paper could be biased may seem surprising, but those of us who remember darkrooms will easily recall the Shirley cards packed with Kodak printers from the 1950s until the 1970s. They were used to calibrate tone during photo processing. The original cards depicted Shirley Page, the white model who posed as the benchmark for proper printing. Thus, the product favored light skin tones while leaving non-white skin underexposed and inaccurate. The bias of Kodak’s film was so notorious that in the late 1970s, Jean-Luc Godard claimed it was racist and refused to use it when working in Mozambique.

Roy DeCarava (American, 1919–2009), Couple Dancing, 1950, printed 1991, Photogravure, Museum purchase, in memory of Alice R. and Sol B. Frank, ©1990 Roy DeCarava, 2002.15.4

Photographers know how to manipulate their materials, and by and large, Black photographers have been especially well versed in using lights, adjusting exposure, and applying darkroom techniques to produce the beauty they want to capture. DeCarava was no different, but unlike his peers who made adjustments to “correct” the medium or compensate for its shortcomings, DeCarava instead sought to exploit them, as seen in Fourth of July.

For DeCarava, the light and shadow and the sense of beauty and mystery Prospect Park imparts may well have drawn his eye to that dappled clearing in 1979 but not simply because of its visual interest. As with his entire body of work, the dark gray tones, unstable shadows, and melancholy beauty offer a visible metaphor for the unsettled tensions of his day—the same contradictions explored in his earlier project and exemplified in its title, The Sweet Flypaper of Life. Then, as now, the Fourth of July holiday was widely celebrated and enjoyed as a time to spend outdoors with friends and family, and that is no doubt what’s happening in this scene. Yet, as DeCarava’s photograph makes evident through its tone and mood, the holiday is not so simple. While the day extols American independence, not all Americans have enjoyed the full promise of freedom equally, even while they celebrate a happy day together.

–Seth Feman, PhD, Deputy Director for Art & Interpretation and Curator of Photography