- Open today, noon to 5 pm.

- Parking & Directions

- Free Admission

Norfolk’s Scope Arena Turns 50

–Lloyd DeWitt, PhD, Chief Curator and Irene Leache Curator of European Art

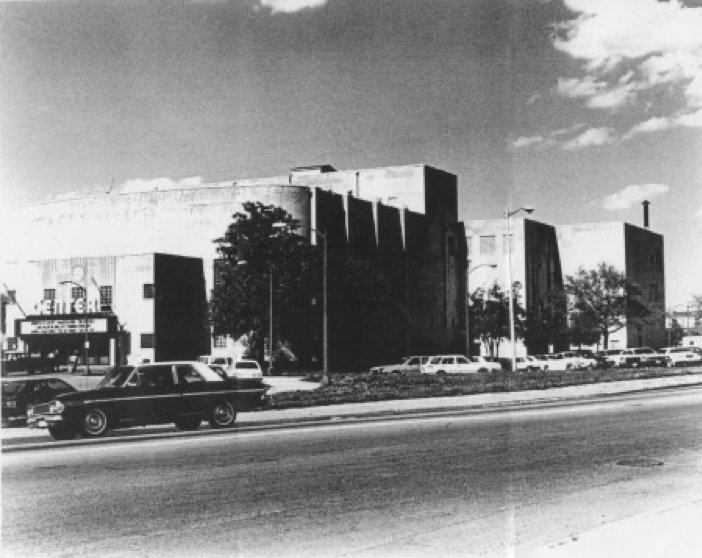

Norfolk Scope Arena and Chrysler Hall, photo courtesy of SevenVenues

The Arena

With 25,000 square feet of floor space and 12,000 seats, Scope arena has hosted approximately 3,876 events and welcomed 17,524,245 guests during the past five decades. It remains the largest venue in Hampton Roads and brought Elvis Presley, John Denver, Bob Dylan, The Eagles, Marvin Gaye, and countless other musicians to Norfolk. The Virginia Squires professional basketball team used the facility, and it is now home to the Norfolk Admirals hockey team. The center also includes a rarely used 65,000-square-foot underground exhibition hall, supported by fifty square columns.

The 443-foot wide arena is among the greatest examples of brutalist architecture in the country and one of the most important modern buildings in Virginia. It remains the largest thin-shelled domed building in the world and has been largely unscathed by heat and hurricanes. It has also endured the slings and arrows of misguided critics, one of whom called it “typical 1970s UFO-inspired monumental architecture…with Star Trek overtones,” embodying “yesterday’s tomorrow.”

Today, “yesterday’s tomorrow” is synonymous with “visionary” and inadvertently corroborates Scope’s Test of Time Award from the American Institute of Architecture. The organization asserted the building “has endured as one of the commonwealth’s most impressive downtown spaces.” Norfolk has Pier Luigi Nervi to thank for Scope’s unique, show-stopping design.

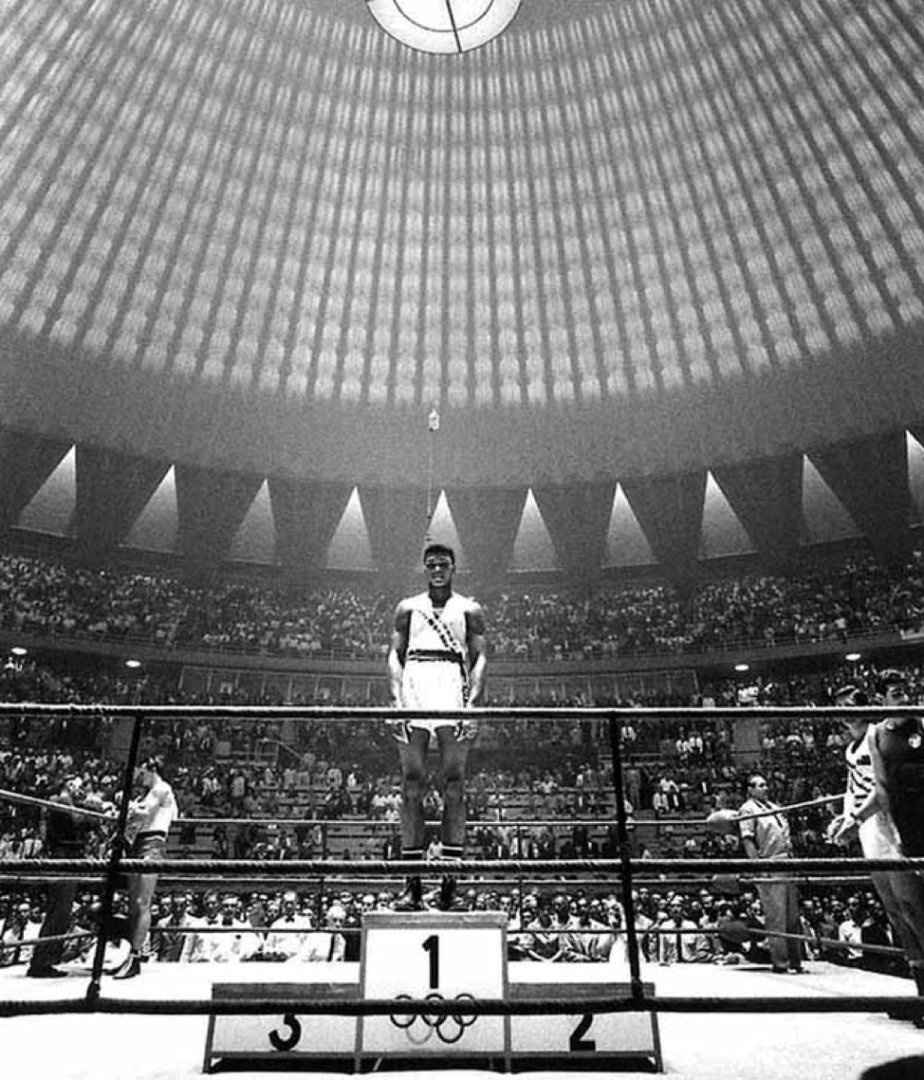

Cassius Clay on the medal podium in the Pallazzetto dello Sport (1958), Rome, 1960

Before designing Scope, the renowned “starchitect” had a remarkable reputation with skyscrapers, bridges, embassies, and stadiums all over the world. Nervi’s Palazzetto dello Sport, the venue of the 1958 Olympic Games in which Cassius Clay won the gold medal in boxing, caught the world’s attention during the first televised Olympic Games, and was one of two Olympic arenas that were the focus of the 1960 Life magazine article that introduced Nervi to the American public.

Pier Luigi Nervi, Palazzetto dello Sport, Rome, 1958. NCSU Libraries Collections

The Inspiration

The Palazzetto, the smaller of the two Rome arenas, became Nervi’s signature masterpiece, featuring a simple shallow dome with a scalloped edge to let in light. The structure was supported by heavier struts around the perimeter that expressed, in the simplest terms, how weight was carried to the ground. Scope’s dome features a cleaner structure than the Palazzetto and almost human-formed buttresses with “feet” that feel more securely anchored than in the Italian building. Nervi’s domes actually expand on two venerable traditions going back to ancient Rome: traditions of public arenas like the Colosseum and of building giant domed structures of concrete cast into molds like the Pantheon temple and Nero’s Domus Aurea, both in the city of Rome. Nervi’s “new Pantheon” added to this ancient technology the strength of steel—specifically sophisticated steel reinforcing mesh. Combined with the use of ribs and grids to carry the weight, this technique resulted in a pattern that more resembled the ceiling of a gothic cathedral, earning Nervi the moniker of “poet of concrete.”

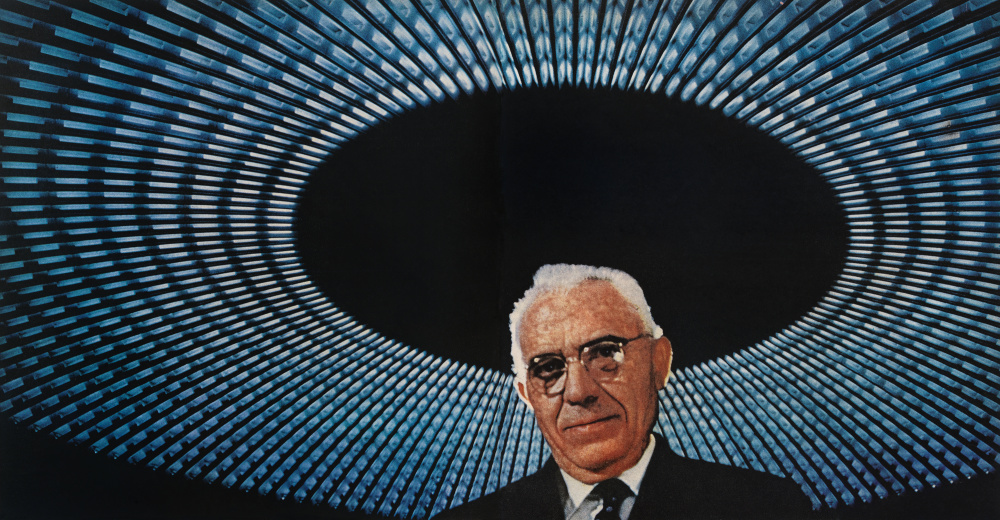

Pier Luigi Nervi in the Palazzetto dello Sport, Life Magazine, June 7, 1960, Photograph by Mark Kauffman

The Architect

Nervi was a renowned and accomplished architect by the time he designed Scope. Born in 1891, he graduated with a degree in engineering from the University of Bologna in 1913. His experimentation in employing concrete for unconventional uses started with the roofs of airplane hangars near Orvieto for the Italian Air Force in 1935 and in grand cantilevered viewing stands in the stadium of Florence, Italy. He worked with Gio Ponti to develop a new skyscraper design for Turin’s Pirelli building that broke with the model of the rectangular box. His design for UNESCO world headquarters reflected this same anti-formalist, “neo-expressionist” impulse. Nervi said, “Concrete is a living creature that can adapt itself to any form, any need, any stress.”

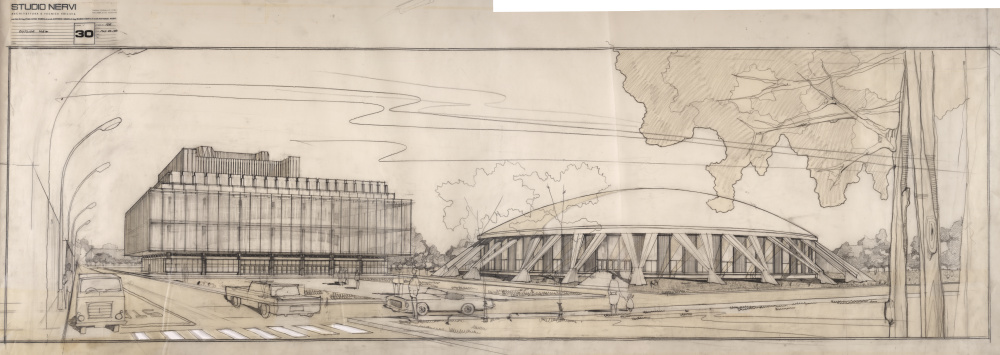

Pier Luigi Nervi Studio, Norfolk Civic Center rendering, May 28, 1966, Sargeant Memorial Collection, Norfolk Public Libraries

Architectural Innovation

Nervi’s engineering ability led him to propose uniquely ambitious and unprecedented designs, using a new technology he developed in which he embedded finer steel mesh in concrete that allowed for stronger and lighter construction. In this case, beauty was born of necessity. After World War II, heavy equipment was in short supply in devastated Italy. In response, Nervi pushed the limits of reinforced concrete and developed methods of pre-casting ceiling coffers and other elements that cut down drastically on the weight and expense of buildings and allowed for far greater spans of vaulting that led him to propose massive domed structures. Instead of enormous cranes, these could be assembled with scaffolding and smaller equipment. The structures consisted of ribs that held grids of thousands of small precast hollow coffers in beautiful patterns that became his artistic signature.

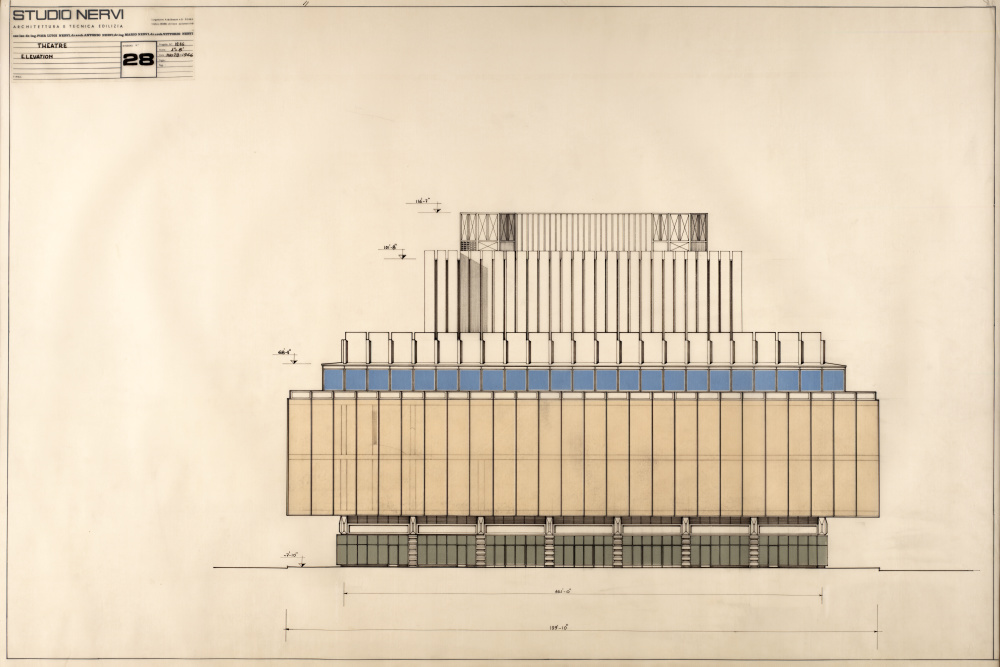

Pier Luigi Nervi, Concert Hall design elevation, Norfolk Civic Center project, 1966, Sargeant Memorial Collection, Norfolk Public Libraries

Designing Scope

Nervi never visited Virginia. He produced the drawings for Scope in his Rome studio from late 1965–1966. Once the basic design was achieved, he tested it in a wind tunnel. This step was key to ensuring the endurance of a radical world-record dome under hurricane conditions. Local firm Williams, Tazewell & Associates, led by the dynamic Norfolk architect E. Bradford Tazewell, Sr., worked with Nervi’s sons to carry out the plan, contracting with Daniel Construction as the builder. Tazewell modified Nervi’s designs in two ways: he departed from the asymmetrical conception of the interior of Scope toward a symmetrical design for the seating but, more importantly, he completely reworked Nervi’s design for the adjacent concert hall.

Tazewell dominated the local architecture scene and estimated that he had completed over 500 projects in the area, including the Norfolk Southern tower and Harrison Opera House. He also served as the local architect for Skidmore Owings and Merrill’s project for a Virginia National Bank building, today the Ikon building. He used New York City’s Lincoln Center as a model for his redesign of the music hall, retaining the classical form of an ancient Greek temple but using columns based on those of Nervi’s arena. His design thus harmonized with both Nervi’s novel domed structure as well as the adjacent 1840 Norfolk Academy building, a masterpiece of nineteenth-century neoclassicism designed by Thomas Ustick Walter, architect of the U.S. Capitol Dome. Tazewell’s design adhered to the “New Formalist” style, which contrasted with Nervi’s neo-expressionist sensibility. Unfortunately, Tazewell’s classic compromise eliminated the counterpoise between Nervi’s two very different modern forms, leaving Scope more of an isolated intrusion into the local landscape, but one whose presence and achievement have not diminished over time. Washington Dulles Airport by Aero Saarinen is Virginia’s other great modern building adhering to neo-expressionist style.

A New Vision for Downtown Norfolk

Beyond the structure itself, Nervi’s design for Scope and Norfolk’s entire civic center complex anticipated a less car-dependent future by embedding the building in a human-scale pedestrian downtown urban landscape. It was intended to form one end of a car-free plaza and square from “Waterfront Drive to Scope.” His plan eliminated the blight of sprawl and parking lots by concealing parking underground, doing away with surface vehicle traffic and giving the urban space over to pedestrians.

Granby Pedestrian Mall, May 1980, Norfolk Housing and Redevelopment Authority

The Days Before Scope

The story of Scope is one of energy, growth, and vision in Norfolk and begins with its predecessor venue, the Municipal Auditorium. Norfolk’s population doubled in the first years of World War II and continued to grow through the Cold War. To provide recreation, especially for its military population, the city commissioned the Municipal Auditorium from Norfolk architect Clarence Neff, who worked in the late “streamlined modern” phase of American Art Deco style. It was originally designed for both performance and sporting events with a 3,618-seat auditorium on one end and a 1,831-seat theater on the other, anticipating the dual function of the 1971 civic center. The project was made possible with $278,000 from the federal government’s War Fund and $245,000 from the City of Norfolk. The venue, known today as the Harrison Opera House, opened in 1943 and was later given to the United Services Organizations (USO) to administer. It was updated in 1993 by Tazewell Architects and remains a major venue in the community, serving as the home of the Virginia Opera.

Norfolk Municipal Auditorium, 1943, photo ca. 1980, Carroll Walker Collection, courtesy Norfolk Public Libraries

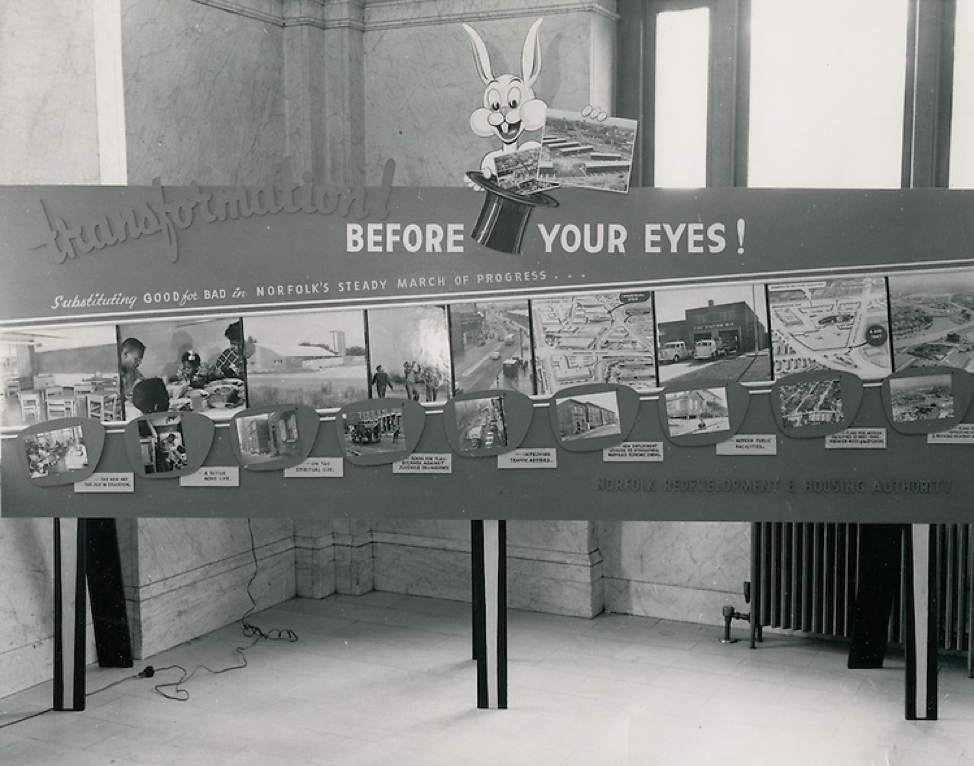

1964 Urban renewal display at City Hall (now Slover Library). Norfolk Housing and Redevelopment Authority

Kenneth Harris (American, 1904-1983), Lost Last Stand, 1961, Watercolor on paper, Gift of the Norfolk Housing and Redevelopment Authority, © Kenneth Harris, 2021.11.5

The city’s wartime population explosion had serious consequences for the civilian population as well, with many war industry workers resorting to living in mobile home parks. The Norfolk Housing and Redevelopment Authority (NHRA) was established by the City of Norfolk in 1946 and allowed Norfolk to be one of the first cities to draw on funds provided through the 1949 Federal Housing Act that fostered large-scale demolition of “dilapidated” housing and “impoverished” neighborhoods, by which they nearly always meant Black neighborhoods. To help make its case, the NHRA commissioned beloved local landscape artist Kenneth Harris to document those buildings in a series of watercolors that included Last Stand (1961). President Lyndon Johnson’s Fair Housing Act of 1965 provided further funds for special projects, prompting Lawrence Cox and A. Willis Robertson to lobby Congress and the Department of Housing and Urban Development for a new, larger cultural and convention center as a “jewel of renewal.” The Federal Government contributed $23 million toward the massive $35-million complex as part of its troubling urban renewal initiatives.