- Open today, 10 am to 5 pm.

- Parking & Directions

- Free Admission

New acquistion: Edward Mitchell Bannister’s Migration at Sunset

– Corey Piper, Brock Curator of American Art

Edward Mitchell Bannister (American (born Canada), 1828–1901), Migration at Sunset, ca. 1880, Oil on canvas, Museum purchase, 2020.22

A sense of pleasing harmony suffuses the entire world that Edward Mitchell Bannister created in Migration at Sunset. While the pastoral subject of a shepherd and his flock suggests a timeless ritual of nature, the free brushwork, earthen tones, and evocative approach align with modern directions in late nineteenth-century art. This recent acquisition marks a significant addition to the Chrysler’s American art collection, adding a key example of the American Barbizon School and a work by one of the most successful and prominent African American painters of the nineteenth century.

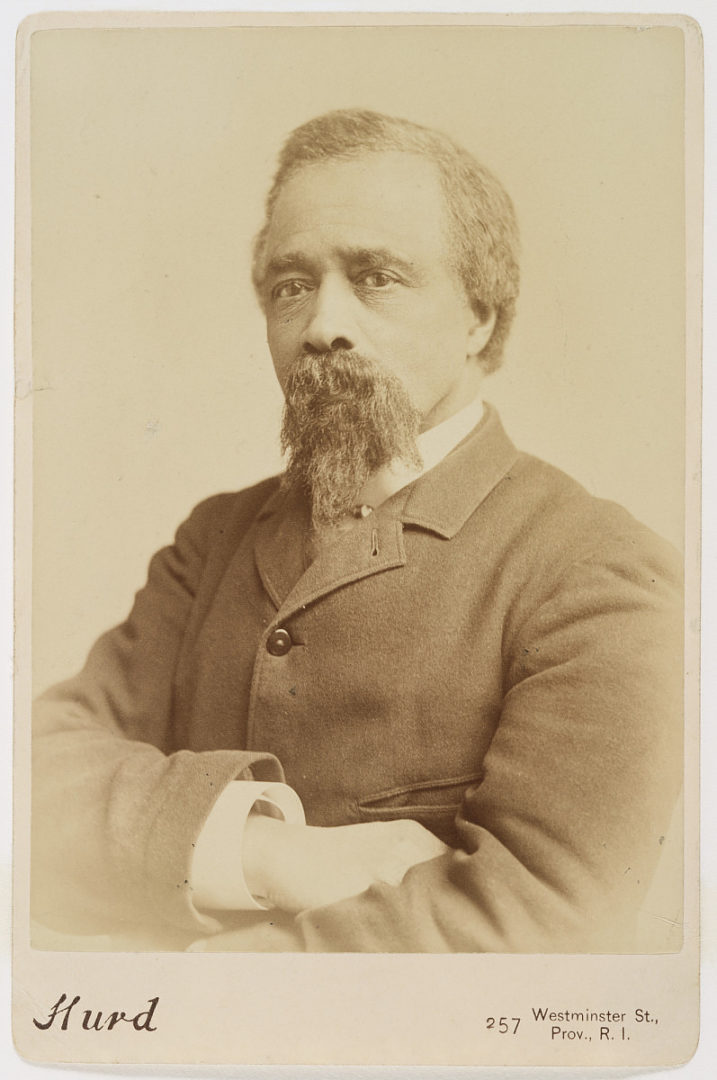

Gustine L. Hurd, (04 Sep 1833–01 Oct 1910), Edward Mitchell Bannister, c. 1880, National Portrait Gallery, Smithsonian Institution; gift of Sandra and Jacob Terner, NPG.76.66

Bannister was born in New Brunswick, Canada but settled in Boston as a young man. There, he worked a variety of jobs while pursuing his early artistic training. He took courses at the city’s Lowell Institute, where he studied under the sculptor and practicing physician William Rimmer.

As a Black artist trying to succeed in the almost exclusively white professional art world, Bannister shared later in life that an editorial in a New York newspaper written in 1867 motivated his artistic pursuits. The article claimed African Americans lacked the ability to produce great art. Bannister provided a definitive rebuttal to the writer’s scurrilous claims at the 1876 Philadelphia Centennial Exhibition, where his painting Under the Oaks (now lost) was awarded a first prize medal, the first national art award bestowed upon an African American artist. The exhibition served as Bannister’s dramatic debut to the American art public and launched his career. He settled in Providence, Rhode Island, where he enjoyed a long and prosperous career as one of America’s leading landscape painters of the late nineteenth century.

Migration at Sunset dates to the period in the late 1870s and early 1880s, during which Bannister established his professional footing and developed a distinctive style and subject matter that defined the bulk of his output. As the sun sets on a verdant landscape, a single shepherd guides his flock home from their daily pasture. The rich earth, sturdy trees, and swirling hues of the dusk sky that surround the figures form a pastoral vision and strong antidote to the urban realities of the industrializing United States. This picture of unity between human labor and industry and the natural world was a hallmark of the Barbizon School, which attracted a dedicated following among American artists and audiences in the late nineteenth century.

Théodore Rousseau (French, 1812–1867), A Clearing in the Forest of Fontainebleau, ca. 1860–62, Oil on canvas, Gift of Walter P. Chrysler, Jr., 71.2054

The American Barbizon School adopted many of its themes and the characteristic loose brushwork and earth-toned color palette from French painters like Jean-François Millet and Théodore Rousseau. The Barbizon School in France united a group of painters who sought to elevate the status of landscape painting and took nature as their primary subject matter. They emphasized painting outdoors and working directly from nature, throwing off the confines of academic studio practice. These painters were particularly drawn to the Forest of Fontainebleau, a former royal hunting preserve that remained sparsely populated and teeming with picturesque attributes of pastoral life. Many painters converged on the small nearby hamlet of Barbizon, which gave the movement its name.

In Boston, Bannister would have surely known the work of William Morris Hunt, the United States’ chief proponent of the Barbizon School. Hunt spent nearly a decade as a young man studying in Europe and France, including two years painting at Barbizon with Millet. When he returned to the U.S., the Hudson River School’s grandiose visions of native landscapes dominated the art world and audiences had little appetite for French styles of painting. As the Hudson River School’s popularity waned following the Civil War, Hunt’s more straightforward and pastoral vision of nature, as seen in paintings like the Chrysler’s Plowing, gained greater currency in the increasingly cosmopolitan American art world.

William Morris Hunt (American, 1824–1879), Plowing, 1876, Oil on canvas, Gift of Walter P. Chrysler, Jr., 71.661

With a steadfast emphasis on truth to nature and timeless themes of agricultural rhythms of life, Bannister’s paintings fueled the growing popularity of the Barbizon school in the United States. He was a particularly prolific painter. Although he stretched his subject matter to include genre scenes, religious subjects, and still life, landscape dominated his output. Bannister frequently painted outdoors in the countryside near his home in Providence, and many studies and sketches survive, evidence of his commitment to close observation and fidelity to nature. Migration at Sunset encapsulates many of the features that made Bannister’s work so desirable and helps connect the histories of French and American painting in the nineteenth century. These stories come to life in the Chrysler’s galleries.

Before Bannister’s painting could go on view, it underwent a transformative conservation treatment, which restored the composition’s original brilliance. Read on with Jennifer Myers, the Chrysler’s NEH Conservation Fellow who takes us through the painting’s material history and details the conservation process.