- Open today, 10 am to 5 pm.

- Parking & Directions

- Free Admission

Local Artist Feature:

Mark Wilson

On October 24 of this wild ride of a year, six artists gathered under the festival tent at the OpenNorfolk Five Points Neighborhood Spot. Contestants in the first-ever 757 Street Art Battle, they gripped brushes and rattled spray paint cans, awaiting the judges’ signal to begin. The free-form live painting competition started, and the artists leapt into action to fill their blank canvases with color, line, and form. During the two-hour paint-off, one artist held his young son in one arm as he rendered a stylized road in a surreal landscape. Another took sporadic dance breaks between her bouts of topographical mark making. A third artist pulled his canvas from a borrowed easel to the ground, crouching on the gravel beside it to bear down onto the surface with layer after layer of oil pastel, brushwork, and text. That artist, Mark Wilson, so impressed the judges with his powerful use of color and expression that he was crowned the victor of the competition.

The soft-spoken Hampton native is a curious match for the frenetic lines and aggressive colors of his paintings. An entirely self-taught painter, Mark holds a master’s degree in Applied Behavioral Analysis from the University of Cincinnati but has no formal training in art or art history. He is a prolific maker upon a variety of media, designing t-shirts and painting thrifted clothing along with the compelling canvases that are attracting dealer attention in Seattle and Europe.

Recently, Mark spent a morning with gallery host Jennifer Hand at the Chrysler Museum. As they toured the galleries, he shared his thoughts on art, accessibility, and the collection.

![]()

JH: You’ve only been painting for a couple of years. Is art new for you, or has it always been a part of your life?

MW: I had an artistic impulse in elementary school. They tried to put me in gifted classes for art, but I didn’t accept it. At the time, sports were more attractive in my eye, and that attitude stuck around through the end of college. I just assumed art was something everyone could do if you tried hard enough.

JH: There’s a lot of energy and emotion in your work, even what seems to be a psychological element. Do you think that your background in behavioral science influences your process?

MW: Yes, and no. I say yes because the fundamental practice of behavioral analysis studies why we do anything at all. When I make a piece that has strong emotion or energy—and it works—I keep that in my toolbox, so I know I have that combination I can always go back to.

JH: Are there artists you look at for inspiration in your work?

MW: I look at all artists for inspiration because I look at art as a way to communicate. Since beginning to make art, I’ll look at anything—even an orange sheet of paper—and reflect on what emotions it brings up, what words it makes me think of. Being a self-taught artist, I try to pull something out of every piece of art I see.

MW and JH enter Come Together, Right Now: The Art of Gathering and pause in front of Oskar Kokoschka’s “Prince Dietrichstein and His Sisters in the Park of the Schloss Weidlingau, near Vienna.”

Oskar Kokoschka (Austrian, 1886–1980), Prince Dietrichstein and His Sisters in the Park of the Schloss Weidlingau, near Vienna, center, on view in Come Together, Right Now: The Art of Gathering, November 2020

MW: Something in this piece communicates fatigue to me. This family—they’re riding something out; it’s just like 2020. Whatever they’re going through, they’re going through together. They’re gonna keep pushing.

JH glances at the label.

JH: It was painted during World War I.

MW: Yeah, that would be it!

MW moves toward Vik Muniz’s “Orestes Pursued by the Furies (Pictures of Junk).”

MW: I actually came here to the Chrysler Museum for the first time two weeks ago. I thought this piece was genius. The difference between how it looks from far away versus coming up close and realizing it’s made of scrap metal, and reading how they had to be so many feet high to take this picture—I think this is amazing. As soon as I saw it, I decided I want to make a piece like this. I hesitate to say that because I know most artists aren’t fond of copying . . .

Vik Muniz, Orestes Pursued by the Furies (Pictures of Junk), right, on view in Come Together, Right Now: The Art of Gathering, November 2020

JH: I mean, it’s funny that you mention that, given that the piece that Muniz copied to make this work is right upstairs.

MW and JH head upstairs to visit Bouguereau’s “Orestes Pursued by the Furies.”

Adolphe William Bouguereau (French, 1825–1905), Orestes Pursued by the Furies, 1862, Oil on canvas, Gift of Walter P. Chrysler, Jr., 71.623

MW: Wow! I would have never made that connection. This is amazing. This work tells me the artist can relate to every emotion he created. He has to be able to feel the pain somewhere in himself to be able to express it like this. This is something really, really special. All of the paintings in this gallery—they’re crystal clear. Every detail makes me want to get close, study how they defined everything, made it so realistic.

JH: Right? When I was little and saw paintings hanging in museums, I didn’t realize there were techniques to art—tools and tricks and rough drafts. I thought you just picked up a paintbrush and created a masterpiece. I thought that’s what being an artist meant.

MW: I feel the same way. I see these paintings, and I think there’s no way that these artists would see what I’m doing now and call it art. But art is a practice; it’s a job. Every day you’ve got to go and put in that work.

MW and JH pause in front of Georges Braque’s “Pink Tablecloth.”

JH: Moments in this work remind me of your style—these colors and abstracted shapes. What do you see in this work?

Georges Braque (French, 1882–1963), The Pink Tablecloth, 1933, Oil and sand on canvas, Gift of Walter P. Chrysler, Jr., 71.624, On view in Gallery 219

MW: These shapes draw you in and hold you; the red is very enticing. I know what these items are supposed to be—the pipe, the cup, the fruit, the eggs—but I can also tell myself that it’s a body; it might not make sense, but I see the shapes as a whole figure looking back at you. It took me a while to realize this special thing about art—that you can see things the way you want to see them. That’s really what I built my practice on.

JH: This Gorky takes that abstraction even further.

MW: It does. I don’t even know how to categorize this piece.

JH: Abstracty suerrealist-ish? I’m not a fan of trying to categorize art into neat boxes. A lot of times, it’s just a way to make art seem more complicated than it really is—to intimidate and gatekeep.

MW: I’m glad you said that. Sometimes, to be honest, I feel intimidated in art spaces and museums. Even if I’ve gotten into a show and I’m talking to another artist in the show, I feel like I don’t know enough terminology—the correct words to use. I feel like my art and my words don’t hold as much weight because I don’t know the language.

JH: That’s so heavy. It feels like we have so much more work to do to invite people into museum spaces and make them feel welcome—make sure they know that art is for everyone.

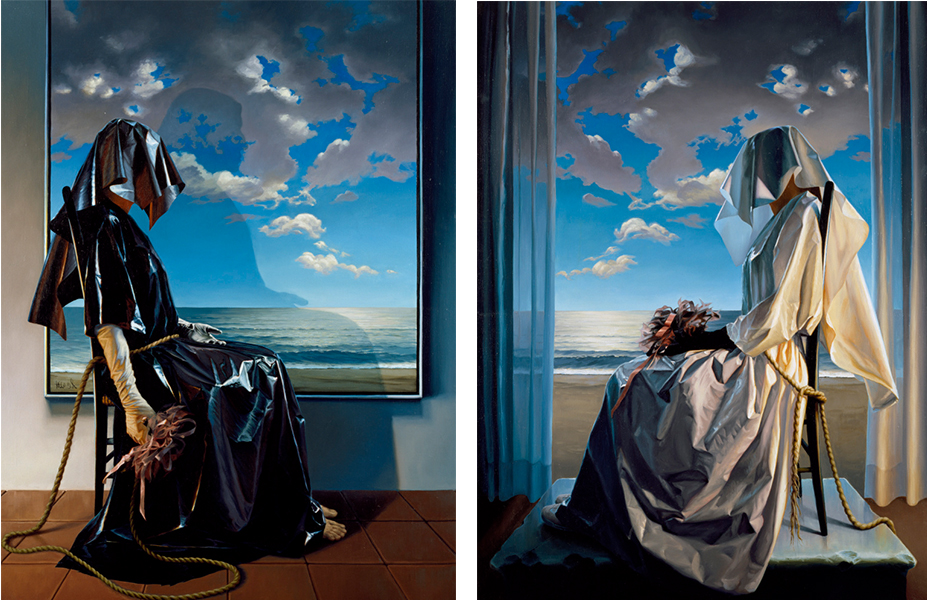

MW stops in front of Komar & Melamid’s “Visit to the Museum of the Revolution from the Nostalgic Socialist Realist Series.”

Komar and Melamid, Vitaly Komar (Russian, b. 1943) and Alexander Melamid (Russian, b. 1945), Visit to the Museum of the Revolution (from the Nostalgic Socialist Realism series), 1981-82, Oil on canvas, In memory of Mary and Dudley Cooper from the family of Joel B. Cooper, 2004.12.3

MW: Seeing art like this reminds me that there are unlimited dimensions of artists out there in the world. You’ll just never run out of ideas, of new things to see. He [the central figure] reminds me of a video game character. He’s cool, he’s tough—the “Call of Duty” type guy. Then the artwork he’s protecting—it’s repulsive. It makes you question what it is, what’s going on. Then the red curtain across the top of the painting makes everything look so formal. I love these three elements because of how different they are, but they exist in the same world in this painting.

JH: And then you have Saya Woolfalk over here, who just created her own world entirely!

MW: This is a whole new level. It is the human experience—how anything you can imagine you can create. Whatever world she’s in, she has a lock on it. It’s more than art for her.

JH: In your artist materials, you refer to yourself as a Christian artist, but you wouldn’t necessarily know that to look at your work. Here we have a Nancy Camden Witt, which is a modernist depiction of the Old Testament story of Hagar and Sarai.

(Left) Nancy Camden Witt (American, 1930–2009), Hagar, 1981, Oil on canvas, Gift of the family of Joel B. Cooper, in memory of Mary and Dudley Cooper, © Nancy Camden Witt, 2002.26.11

(Right) Nancy Camden Witt (American, 1930–2009), Sarai, 1981, Oil on canvas, Gift of the family of Joel B. Cooper, in memory of Mary and Dudley Cooper, © Nancy Camden Witt, 2002.26.12

MW: The artist went somewhere deep to pull this out. I love that about referencing the Bible in my work, and I love that about this piece. It shows both the light and the darkness. For me, you can be a Christian and read the Bible, but everything’s still not rainbows and sparkles. You’re still human; you still deal with darkness.

MW guides them to No. 5 (Untitled) by Mark Rothko.

Gallery 223, McKinnon Galleries of Modern & Contemporary Art, 2018

MW: I’ve obviously heard about Rothko. Just googling to learn more about art, he’s impossible not to come across. When I saw his work online, I didn’t get it. But this is one of the first ones I’ve seen in person, and it does something to my brain . . . makes me lose thought. You hear about paintings doing that to people, but when I actually felt it for myself, it was very, very weird. And seeing that, I want to do that in my own artwork. I want to be able to transfer energy so that whatever I put on the canvas, I can deliver that to the viewer. I feel like this painting does that, and it’s so weird because I wouldn’t expect for this to do it to me.

JH: It’s almost like Rothko is really good at getting people to toe-dip into modern art. It’s a lot harder to start at, like the Richenburg behind us—which, to be diplomatic—isn’t going to be everyone’s favorite artwork.

MW – No, it’s not mine. But art is limitless. There are no bounds. There are probably just as many people out there who that is their thing. So yeah, if it communicates to you, it’s doing what it’s supposed to do.

JH guides them toward the “Last Judgment.”

JH: So, we can’t walk past the Marx Reichlich without a little pause and a discussion because this piece is one of the best conversation starters in the whole museum.

MW: This is a dangerous piece. I love this piece. To me, this is optimum goals of storytelling, detail, expression.

Marx Reichlich (South German, active ca. 1485–1520), Last Judgement, ca. 1490, Oil and tempera on wood, Gift of Walter P. Chrysler, Jr., 71.3098

JH: Boot goals, for sure.

MW: Right, that’s what I’m saying! Like, where did they miss? They hit everything, from the crowns on the heads to the demon with the face in the butt. I try to take little details like that that I find and use them in my own work, so don’t be surprised if you see me put a face in a butt in a painting. But at the same time, the scene is so holy with Jesus sitting on the rainbow, which is clutch. To make this piece, the artist was drawing from intellect, from visions, from dreams. It’s probably one of the best paintings I’ve ever seen—and timeless, too.

JH: And here we come to another Bible story: Lot and His Daughters. More dark subject matter—thanks, Old Testament!

Bonifazio de’Pitati (Italian, 1487–1553), Lot and His Daughters, ca. 1545, Oil on canvas, Gift of Walter P. Chrysler, Jr. 71.622, On view in Gallery 204

MW: I just read this story, too. It’s striking to me because when I read these stories in the Bible, I try to make them relate to me personally, so I can put the lesson to use in my life. I don’t picture anything like this, and it gives me chills to imagine depicting what these stories look and feel like to me.

JH: It’s almost like how Renaissance patrons wanted themselves painted into the works they commissioned to put themselves in the action.

MW: I was not aware that was a thing. Wow! That’s so cool. I’m going to take something from that. I have to. I think I’ll spend the next week taking everything we saw today and putting it into practice. I’m going back to the drawing board.

Thomas Cole (American, 1801-1848), The Angel Appearing to the Shepherds, 1833-34, Oil on canvas, Gift of Walter P. Chrysler, Jr., in memory of Edgar William and Bernice Chrysler Garbisch, 80.30, On view in Gallery 211

JH: Well, let’s get you back to painting, then! Last stop, the Thomas Cole. Final thoughts?

MW: It’s funny. This painting makes me wonder what this event would look like in our time. These figures—they’re praying, but I don’t sense fear. If this happened in a city in the modern day, there would be cars crashing, people running. But this scene is full of peace—acceptance. It’s special.

Experience these artworks and many more during your next visit to the Museum. Reserve free timed tickets for an in-person visit or explore the collection virtually with our online tour of the galleries. Mark Wilson’s recent painting and those of the other Art Battle contestants will be available in an upcoming auction hosted by the 757 Art Battle organizer Poetry Jackson. Find out more about Wilson’s work by visiting his website and following him @surfdontfall on Instagram.