- Open today, noon to 5 pm.

- Parking & Directions

- Free Admission

Liquid Visions: Colorless Glass and Rock Crystal Quartz

–Carolyn Swan Needell, PhD, Carolyn and Richard Barry Curator of Glass

The transformation of sand and other ingredients into molten glass seems to belong in the realm of alchemy. So too does the ability of glassmakers to manipulate the appearance of glass to replicate other materials and substances. The color, opacity, and surface effects of natural stones, gems, and minerals have been imitated throughout the history of glassmaking by a wide variety of cultures, and this is readily apparent when observing the Chrysler Museum of Art’s extensive glass collection. Semi-precious lapis lazuli was copied into dark blue glass to make the Hellenistic Greek Amphoriskos, while Friedrich Egermann’s Beaker demonstrates how nineteenth-century Bohemian glassmakers developed novel glasses that copied banded hardstones like agate.

LEFT Hellenistic Greek, Amphoriskos, 599–400 B.C., Core-formed glass, Museum purchase, 63.60.1 RIGHT Friedrich (Bedřich) Egermann (German, 1777–1864), Beaker, ca. 1820–40, Blown and cut Lithyalin glass, Gift of Dr. Eugen Grabscheid, 58.37.30

The long tradition and interest in making glass that imitated rocks and minerals also spurred the production of perfectly transparent and colorless glass to replicate the pure quartz mineral known as rock crystal. Examples of rock crystal are showcased alongside colorless glass from the Museum’s permanent collection in Clear As Crystal. This exhibition of historical and contemporary glass artwork demonstrates an impressive range of forming and decorating techniques that have been used to achieve a desired effect, such as blowing, molding, casting, pressing, cutting, carving, laminating, engraving, etching, and polishing.

It’s not hard to understand why rock crystal has captured human imagination over the millennia or why people might have sought to create an artificial version of this natural mineral in glass. Rock crystal is the colorless variety of quartz, which is composed solely of silica in its pure state and is crystallized in a rhombohedral system. The mineral is light-weight, transparent or translucent, refractive, and can be carved into ornaments, jewelry, and vessels. Large chunks or unusual specimens of the natural crystal have been considered marvels in and of themselves. There have been countless magical or symbolic meanings, beliefs, and properties associated with rock crystal. Veins of rock crystal quartz may be found all across the globe, although the major geological sources that were known and exploited for much of early history include Madagascar, India, and the region of the Alps.

The origin of the term “rock crystal” for the colorless variety of quartz is the Greek word for ice (κρύσταλλος, krystallos). This term reflected a popular notion during much of antiquity that rock crystal was only formed in very cold regions, like mountain peaks. It was believed that when water froze at such extreme temperatures, it was impossible for it to melt ever again. Rock crystal was considered to be a miraculous substance, rare and beautiful. The fourth-century Latin poet Claudius Claudianus (ca. 370–404 CE) captures these notions in a section of his Epigrams devoted to Wonders:

“This piece of ice bears the trace of its original nature: in part it has crystallized, but in part has resisted the cold. It is a game or trick played by winter, rendered all the more precious by its imperfect crystallization. This jewel prides itself on the moving wave it holds captive. You droplets of water, who hold your sister captive within your icy prison, remaining liquid in part yet in part no longer so, what force enchains you? What cold cunning both froze and liquefied you, marvelous block?” (translation from Sylvie Raulet in Rock Crystal Treasures from Antiquity to Today).

The transparency and colorlessness of krystallos reminded the Greeks of water, while the hardness of the substance led them to consider it to be an extreme form of ice. The aqueous and icy associations of rock crystal quartz are by no means unique to the Greeks, however. These notions become readily apparent when considering the Carp Ornament and the Diver Vase, both on view in Clear As Crystal.

This nineteenth-century Chinese ornament was carved from a single, clear block of rock crystal quartz. The mineral was given the form of an oversized fish, likely a carp, with a male figure seated atop its head. Chinese ornaments from this period were often carved from hardstones and jade. When the material was selected for this particular carving, the craftsperson took clever advantage of transparent, colorless rock crystal quartz and its sensory and linguistic links with water. Rock crystal is known by several names in Chinese, including shuijing (水晶, composed of the words “water” shui 水 and “brilliant” jing 晶) and shuiyu (水玉, meaning “water jade”). There are also links between the symbolism of the raw material and its carved imagery. In Chinese visual culture, a fish conveyed wishes for wealth and prosperity because the word for fish (yú, 魚) is a homophone that also translates as “abundance” (yù, 裕). Rock crystal was highly regarded in China as a material with prosperous associative symbolism, and it was even called “the elite among stones.” The Chrysler’s rock crystal quartz ornament was produced during the Qing Dynasty (1644–1911), a flourishing moment for the lapidary arts.

Chinese, Carp Ornament, ca. 1850–99, Carved and polished rock crystal quartz, Gift of Mrs. Jefferson Patterson, 79.297

The thematic interest in fish and its depiction on decorative arts produced in China may be seen in another object in the Chrysler’s glass collection, a nineteenth-century snuff bottle made of colorless and blue glass. The transparent and colorless glass is very bubbly, and was no doubt a cheaper way to achieve the symbolic associations and material properties of the esteemed “water jade.” To make this particular bottle, blue glass was used to encase the entire vessel and was then selectively carved away to define the form of the fantail carp and to reveal the colorless glass beneath it.

Chinese, Snuff Bottle, ca. 1825–75, Blown glass, cased, cameo-carved, Gift of Walter P. Chrysler, Jr., 80.32.7a&b

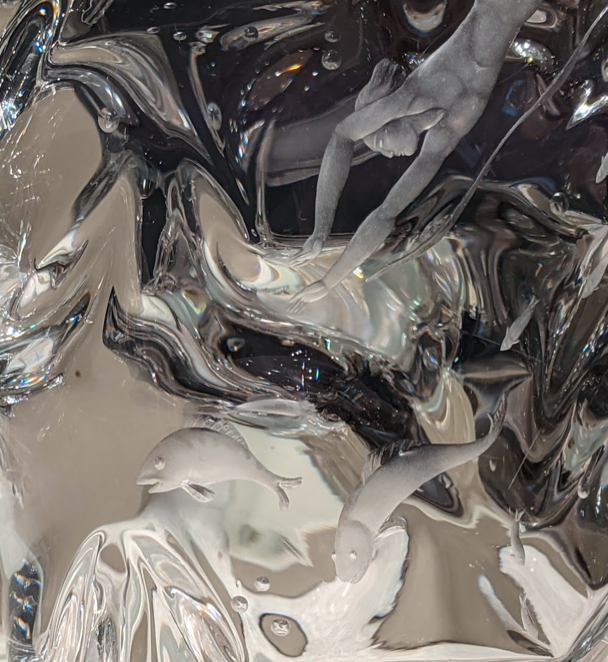

In the early twentieth century, Orrefors Glasbruk in Sweden also explored fishy imagery and conjured the flow of water by means of a colorless material, although in this case with crystal-clear glass. The manufactory began producing modern art glass using very high-quality colorless glassware in 1916. Orrefors hired two gifted designers to work closely with the factory’s skilled glassblowers, one of whom was the portrait and landscape painter Simon Gate. Gate designed the Diver Vase, a large tumbler-shaped vessel with mold-blown walls that undulate inwards and outwards. Tiny air bubbles trapped within the glass heighten the illusion of cool and watery depths that ripple with life. Light passes through the colorless and transparent glass, refracting to create glittering effects, and spills across the tabletop. An engraved male figure dives downwards at an angle, swimming alongside several engraved fish. The areas of engraving have not been polished, leaving a frosted matte appearance that evokes something more solid and stands in contrast with the elusive and watery quality of the glass of the vase itself.

Designer, Simon Gate (Swedish, 1883–1945), Manufacturer, Orrefors Glasbruk (Swedish, founded 1898), Diver Vase, ca. 1935–40, Mold-blown and engraved glass, Gift of Daniel Greenberg and Susan Steinhauser, 2016.40.7

Diver Vase (detail), ca. 1935–40, Mold-blown and engraved glass

Diver Vase (detail), ca. 1935–40, Mold-blown and engraved glass

Orrefors apparently found colorless glass to be a medium uniquely suited to aqueous themes, as evidenced by another vase in the Chrysler’s collection by Gate’s design partner Edvard Hald. The artist used the graal technique to encase colorful fish and underwater plants in thick layers of colorless glass.

Designer, Edvard Hald (Swedish, 1883–1980), Manufacturer, Orrefors Glasbruk (Swedish, founded 1898), Vase, ca. 1948–1950, Graal glass, Gift of Walter P. Chrysler, Jr., 0.2500

The Carp Ornament and Diver Vase are two objects highlighted in Clear As Crystal that beautifully demonstrate how artists could cleverly engage with the sensory links that may be found between colorless materials and water: natural rock crystal quartz in one case and artificial colorless glass in the other. People have long used both rock crystal and glass to create beautiful artworks, pleasing to the senses and evocative of the earth’s more elusive natural elements.

Clear as Crystal: Colorless Glass from the Chrysler Museum is on view through July 11, 2021.