- Open today, noon to 5 pm.

- Parking & Directions

- Free Admission

Bringing the Chrysler Collection Home: Jean Outland Chrysler’s Devotion to Norfolk

–Jeff Harrison, Curator Emeritus

The concept of the arts as a civic obligation—as a necessary cultural feature of any American city aiming to be great—took root in Norfolk in large measure due to the efforts of enterprising women. In 1871, Irene Leache and Anna Wood arrived in the city and established the Leache-Wood Seminary, a school for girls that featured instruction in the arts. Wood went on to establish the Irene Leache Art Association to promote the arts in Norfolk. Florence Sloane, a New York transplant, established with her husband, William, the city’s Hermitage Museum and Gardens and played a key role in the founding of the Norfolk Museum of Arts and Sciences in 1933. Those pioneers have inspired generations of dedicated women who have selflessly given their time and treasure to the area’s cultural advancement, among them the members of the Irene Leache Memorial, the Norfolk Society of Arts, and the Chrysler Museum’s volunteer docent corp.

Jean Outland Chrysler

Yet one woman stands apart in her singular commitment to, and extraordinary influence on, the Museum and the region’s broader cultural life. Jean Outland Chrysler played a critical—indeed decisive— role in one of the most significant moments in the modern history of American museums in 1970-71 when the Norfolk Museum of Arts and Sciences received an enormous, epoch-changing gift of art. In August 1970, after careful courting by the Norfolk town fathers, Jean’s husband—Walter P. Chrysler, Jr. of New York and Provincetown, Massachusetts—officially agreed to donate nearly 8,000 works of art from his nationally known collection to the Norfolk Museum. The gift was a veritable treasure trove of European and American paintings, sculptures, glass, silver, and furniture. Overnight, it transformed a small, local museum known mainly for its natural history displays and modest period rooms into one of the nation’s foremost arts institutions. The Norfolk Museum was quickly renamed the Chrysler Museum of Art in honor of its newfound patron. Chrysler’s patronage would extend another eighteen years until his death in 1988. Throughout that period, he gave hundreds of additional works—a torrent of paintings, sculptures, and decorative arts objects—that dramatically expanded upon his initial donation and cemented the Chrysler Museum’s role as the chief cultural resource of Virginia’s Hampton Roads region and one of the premier fine arts museums in the southeastern United States. As Walter’s devoted, art-loving wife, Jean labored alongside him for decades to build the collection and was key in the choice of its ultimate home. Without her, Norfolk might never have had a Chrysler Museum of Art.

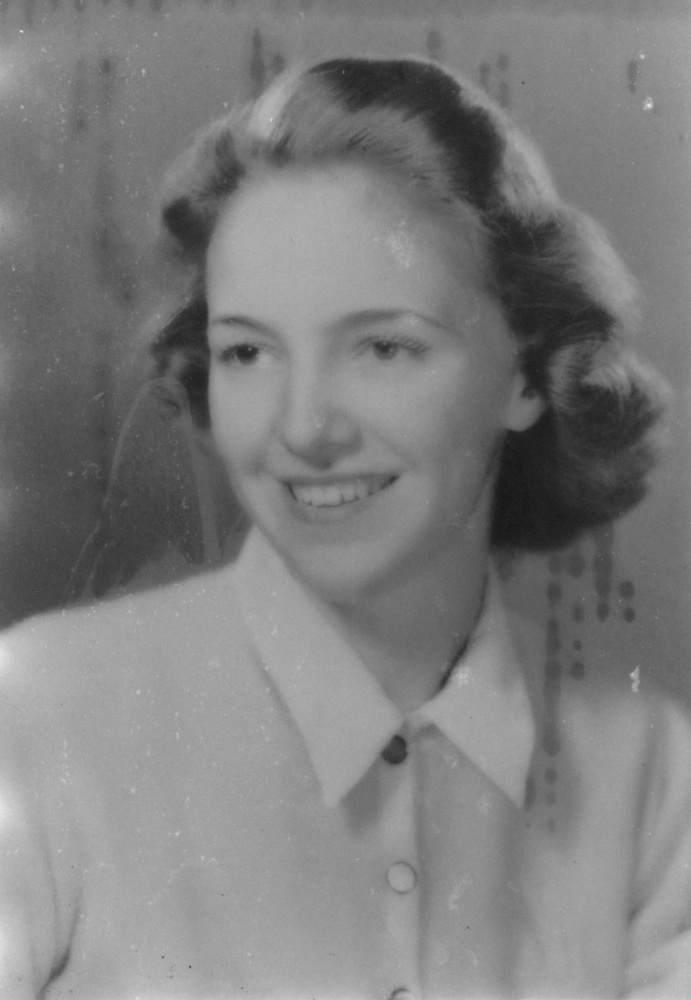

Jean Esther Outland, ca. 1940

Jean Esther Outland was born on September 15, 1921 in South Norfolk (today part of Chesapeake, Virginia). She was the second of four children born to Lida Ann Maddox Outland and Grover Cleveland Outland. Grover Outland worked as a school principal and insurance salesman and, in time, entered the Virginia House of Delegates. As his prospects improved, the family moved from South Norfolk to the more affluent Edgewater neighborhood in Norfolk. Jean attended Norfolk’s Maury High School and, in 1942, graduated with a B.S. degree from the College of William and Mary. She then began work as a physical education instructor at William and Mary’s Norfolk Division (today Old Dominion University).

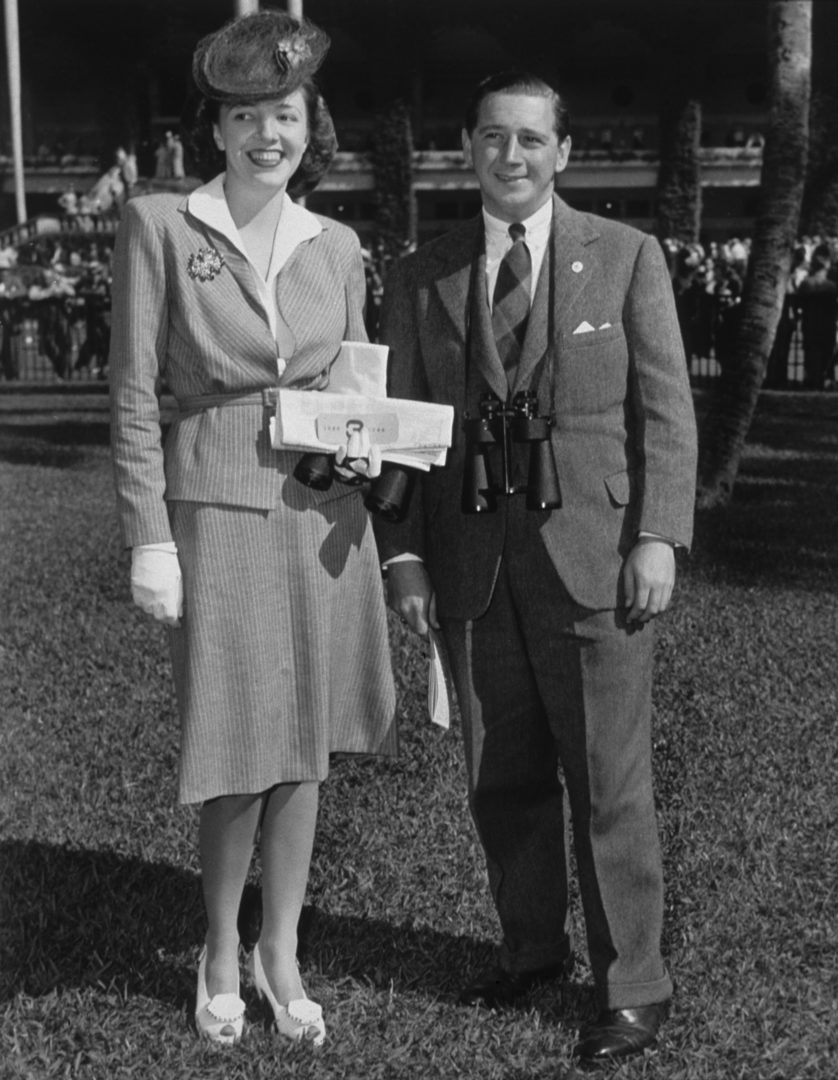

Walter P. Chrysler, Jr. and Jean Esther Outland, 1940s

Jean’s quiet life as a young, middle-class working woman dramatically changed in the early 1940s when she met Walter P. Chrysler, Jr., a son and heir of New York’s powerful Chrysler family of car-company fame. Walter had recently joined the Navy as a lieutenant junior grade and been posted to Norfolk. He first encountered Jean, some say, at a dance at the Cavalier Hotel in Virginia Beach. Others claim that they met on a Norfolk streetcar and Jean, offering southern hospitality to a man in uniform far from home, invited him to dinner with her family. Jean and Walter’s budding relationship was interrupted when Walter received another posting, this time to Key West in Florida. But he returned in late 1944, made his intentions known, and invited her to North Wales, his country estate near Warrenton in northern Virginia. There, he proposed to her, and on January 13, 1945, the two married in a modest ceremony in Norfolk’s Freemason Baptist Church. He was thirty-five years old; she was twenty-three.

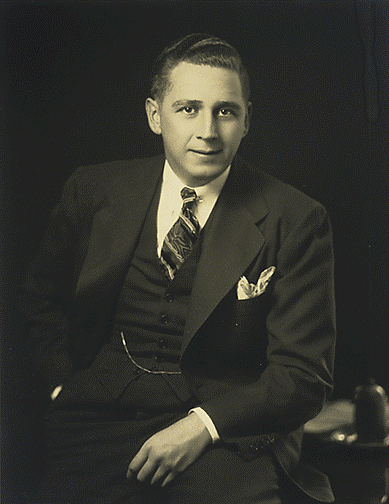

Walter P. Chrysler, Jr., 1940

It is difficult to know what the Outlands thought of the wealthy, prominent New York business scion who appeared improbably on their doorstep and began a whirlwind courtship of their daughter. They must have discovered that he was previously married to a Manhattan socialite named Marguerite (Peggy) Sykes. The marriage had been troubled and brief, lasting little more than a year and a half and ending, at Peggy’s insistence, in a 1939 Reno divorce. They also must have thought it strange that Walter abruptly left the Navy while still in Florida, an odd turn of events in the midst of World War II. More than likely, they did not discover the probable reason for either his divorce or dismissal from the service: he was gay and, like most American gay men at the time, was trying to live a closeted life. In any event, the Chrysler family probably suppressed any scandal that might have arisen from either event. Like Peggy Sykes, Jean must have discovered the truth soon enough about Walter’s sexual orientation. Yet, she resolved to stay in the marriage. She and Walter would work tirelessly to build his collection and establish a museum to house it, and though they had no children, their marriage lasted a full thirty-six years until Jean’s sudden death in Norfolk in 1982.

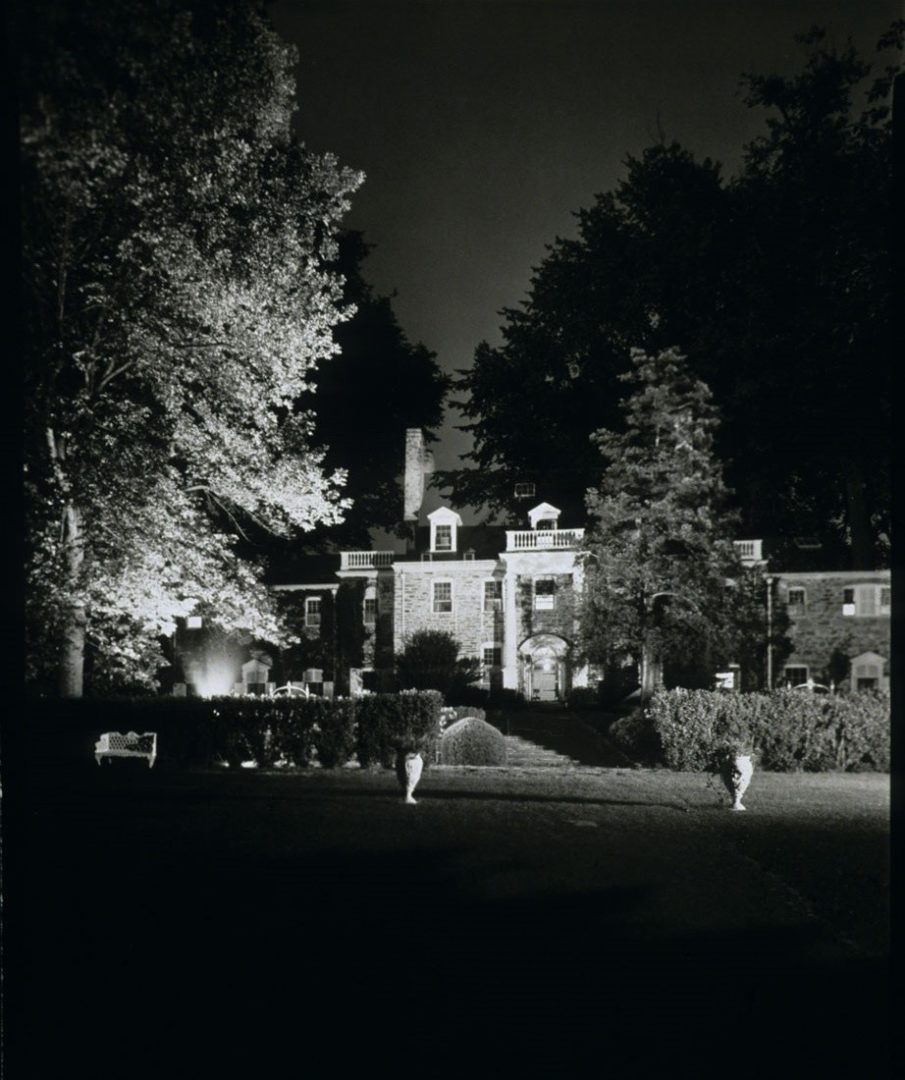

North Wales

After a honeymoon in Hot Springs, Virginia, Jean and Walter settled at North Wales. Walter had purchased the mammoth estate in 1941, in part to breed and race thoroughbred horses. The eighteenth-century house encompassed seventy-two rooms, including a ballroom, trophy room, and hunt room. The servants’ quarters alone boasted fourteen rooms. The surrounding estate was equally grand. In addition to the requisite horse stables and training track, the grounds featured a golf course, lake, and even a private airfield. Jean suddenly found herself surrounded by luxury, living among Walter’s spectacular collections of French modernist paintings and eighteenth-century English and continental furniture.

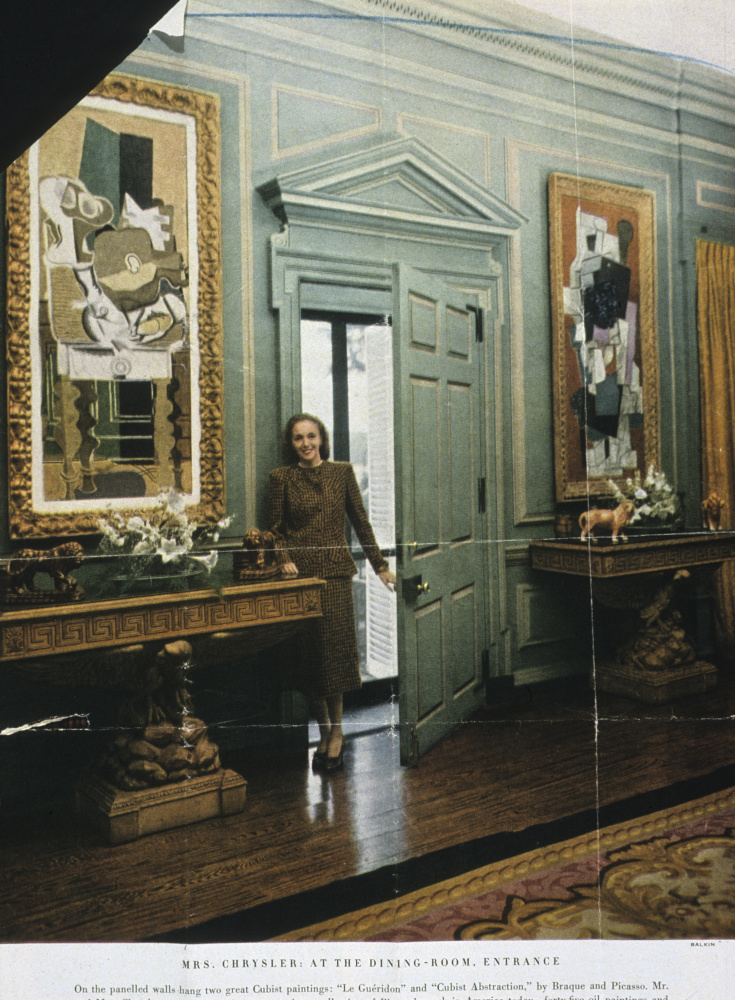

“Mrs. Chrysler: At the Dining Room, Entrance” Vogue Magazine, April 15, 1948

Walter P. Chrysler, Jr. and his wife, Jean Outland Chrysler, pose for a photograph at the Kentucky Derby in 1945.

She assumed the roles of matron of North Wales and hostess in charge of dinners, receptions, and other social events. While Walter tended to his horses or business in New York, she developed a life-long enthusiasm for pure-bred Chihuahuas. Many in Norfolk still recall her daily arrivals at the Museum in the 1970s with her miniature dogs in tow, her prized Abigail nestled in a wicker basket.

Jean with her Chihuahuas, North Wales

Jean also joined Walter in New York, where the two had a luxurious Park Avenue apartment and box seats at the Metropolitan Opera. Opera would become one of her abiding passions. Indeed, during the early 1950s in New York, Walter nurtured a range of cultural interests and activities far beyond art collecting. They included fine book publishing, Broadway plays (he produced several, among them the musical revue New Faces of 1952), and Hollywood movies (he financed the 1953 Joe Louis Story). He even took to boating after purchasing bandleader Tommy Dorsey’s yacht. Jean surely accompanied her husband on many of these ventures and outings, meeting an ever-widening array of celebrities and cultural movers and shakers.

Christopher Clark (American, 1903–1973), Jean Outland Chrysler, 1949, Oil on canvas, Gift of Jean Outland Chrysler in tribute to her parents, Mr. and Mrs. Grover Cleveland Outland, 63.58.6

These were the glamour years for Jean, marked by exclusive premieres and other elite social events, which she attended in dazzling couture gowns. (Several of her gowns were later featured in Norfolk in the Chrysler’s 1983 exhibition, Mystique and Identity.)

Jean dancing with her brother Grover, Jr., North Wales, 1940s

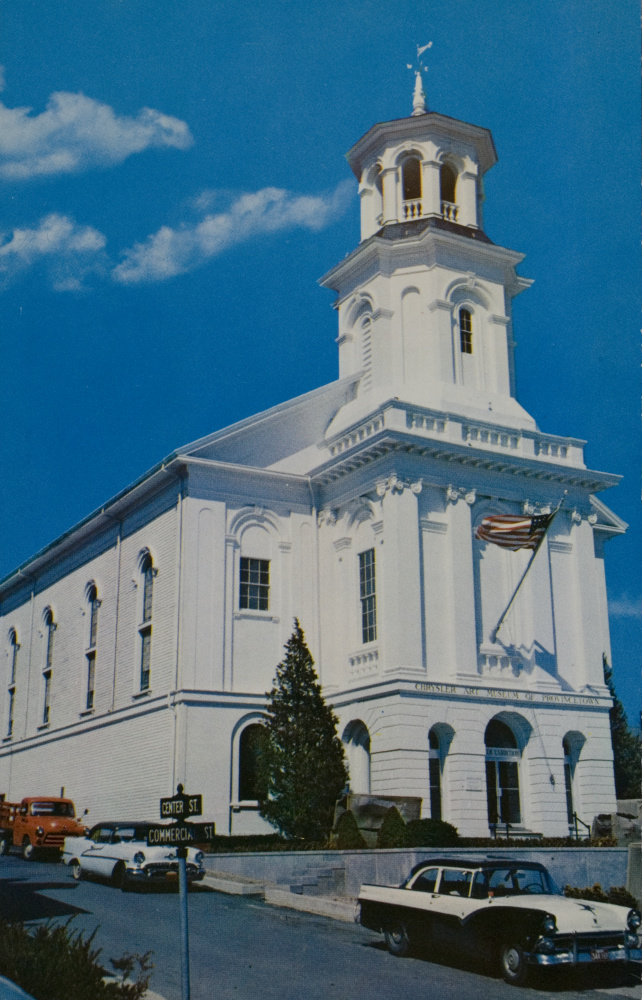

Walter’s art collection fundamentally changed during the 1950s, when he sold or traded most of his French modernist art to buy an increasingly diverse collection of European and American painting, sculpture, and decorative arts. And he became more focused on establishing a “Chrysler” museum to house it. That notion solidified into a bonafide action plan toward the end of the decade, prompted in part by two Chrysler family tragedies. In 1957, his sister Thelma, a New York socialite and an art collector in her own right, died of leukemia in Manhattan. She was fifty-five years old. A year later, Walter’s brother Jack died suddenly of a heart attack at age forty-six. Struck by the tragic randomness of those events and suddenly finding himself the family’s lone male standard-bearer, Walter resolved, at last, to focus on his life and create a personal monument to carry the family name. Shortly thereafter, he purchased the deconsecrated Central Methodist Church in Provincetown, Massachusetts, which he rapidly renovated and opened in July 1958 as the Chrysler Art Museum.

Chrysler Art Museum, Provincetown, MA

The couple’s arrival in Provincetown marked the end of Jean’s glamorous New York life. The two kept their apartment in the city, where they still spent part of the year and Walter continued to collect. But they gave up the rest of their patrician trappings: their yacht, her jewelry, his horses, and their lavish entertaining. They traded their chauffeured limousines in New York for the bus and subway. Her staff now gone, Jean cooked the family meals and even tended to the fireplaces when their Provincetown house got chilly. Walter sold off North Wales, cashed in his stake in the Chrysler Building, and gave up any lingering association with the family business. From then on, they directed every dime and all their energy to the museum and the growth of the collection. The change seemed to energize them both.

Jay Milder (American, b. 1934), Jean (Portrait of Jean Outland Chrysler), 1970, Oil on canvas, 2014.9

With its laid-back atmosphere and vibrant summer artist colony, Provincetown proved a salutary spot for the Chryslers. The museum quickly became the centerpiece of the town’s artistic life. Jean and Walter sponsored scores of special exhibitions and other museum events, and they entertained and served as patrons for the many painters and sculptors who flocked to Provincetown to work and study. Jean also developed a vocation that would engage her for the rest of her life: building a proper library that would serve an art museum’s academic needs. She began to collect art books, periodicals, clippings, and other bibliographic materials that would soon form the nucleus of a genuine research library. Her interest was already apparent in childhood games, where she would “check out” family books to her siblings and then exact small fines when they were “returned late.” Working in the dank basement of the Provincetown museum, she would ultimately catalogue nearly 50,000 volumes by the time she and Walter moved to Norfolk.

By the late 1960s, life in Provincetown had begun to pale for the Chryslers. The museum building had long since proved too small for Walter’s ever-expanding collection. More critically, the town, with its limited budget, could not satisfy Walter’s continual demands for new municipal services, which included everything from help with the museum’s light bill to a new parking lot. The acrimonious standoff led to years of frustration, and in 1969, Walter finally began to search for a new home for the collection. He wanted a city with adequate municipal coffers, a proper museum building, and a willingness to rename that building the Chrysler Museum. Museums across America—147 of them, it was said—made bids for his art. The Chryslers honed the list to fifty and began to vet the candidates.

Jean Outland Chrysler Collection, February–March 1963, Norfolk Museum of Arts and Sciences

Throughout her years in North Wales, New York, and Provincetown, Jean had maintained steady communications with her hometown and its museum. In 1963, she donated forty-two works from her own collection of contemporary art—paintings, sculptures, and works on paper—to the Norfolk Museum. Jean made the gift in honor of her parents, and it was heralded with an exhibition titled The Jean Chrysler Collection. Additional gifts followed in the late 1960s. In 1967, the Chryslers marked the opening of the Norfolk Museum’s Willis Houston Memorial wing with a major loan exhibition, Italian Renaissance and Baroque Paintings from the Collection of Walter P. Chrysler, Jr. In 1969, Walter joined the museum’s board of trustees.

Norfolk Mayor Roy B. Martin, Jr. with Walter and Jean, Norfolk, 1967

In fact, Jean had long harbored the desire to settle her husband’s collection in Norfolk. When he began his search for a new museum, she immediately sprang into action and began working as a double agent on the city’s behalf. After Walter told her that Norfolk had not yet made a bid, she hit the phones to alert the town fathers and get the ball rolling. One story has it that she called Norfolk’s mayor, Roy B. Martin, Jr., to bring him quickly up to speed. She then got Walter on the line so that the mayor could make his pitch. Walter expressed interest, and shortly thereafter, Norfolk banker Jack Gibson and another city representative flew to Provincetown to meet with the Chryslers and see the collection firsthand. Their assessment was glowing, and in August 1970, Walter arrived in Norfolk to begin final negotiations. The rest is history.

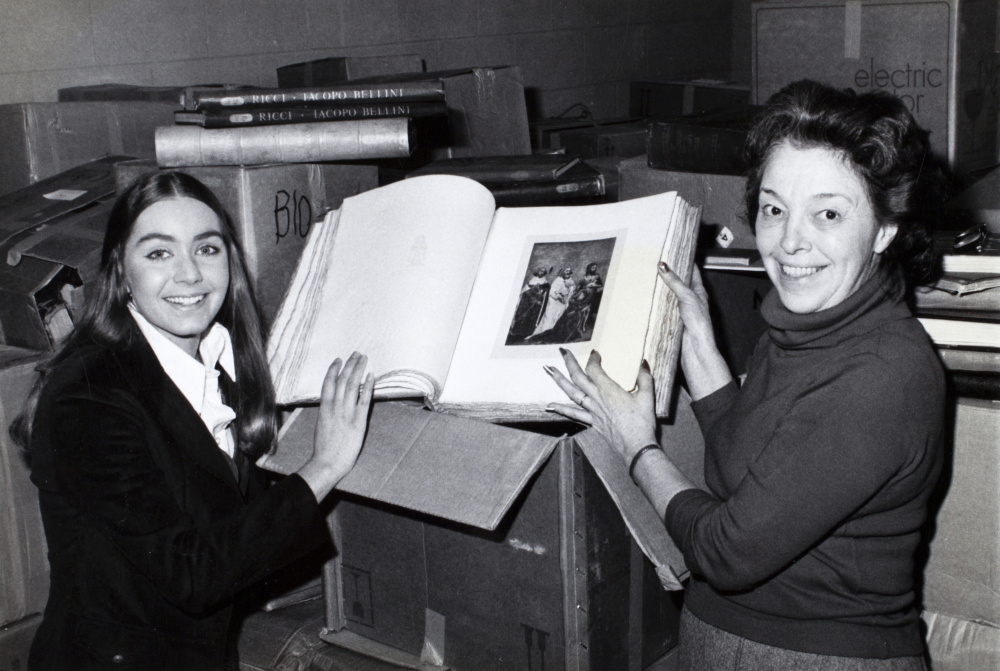

K. Weeks and Jean amid boxes of library books, Norfolk, ca. 1980. Taken by Brooks Johnson at the Chrysler Museum.

Jean’s passion for the arts and community service continued unabated after her return to Norfolk. She served on the Chrysler’s board of trustees from 1977 until her death and donated scores of decorative arts objects to the Museum, including rare examples of French Art Nouveau glass. She was active at her alma mater, William and Mary, and in Norfolk’s Virginia Opera. She was a member of the Virginia Opera Association’s board of trustees and secretary of its executive committee. She was regularly honored in both Tidewater and Richmond for her contributions to Virginia’s cultural life. But her greatest legacy to the Museum and the region sprang from her abiding love of books. She brought the art library she had built in Provincetown with her to Norfolk in 1971 and merged it with the modest book holdings of the former Norfolk Museum. She continued to catalogue the collection and attended classes at William and Mary to perfect her cataloging skills. With her enthusiastic backing, the library expanded dramatically in 1977 when Walter purchased the contents of the incomparable reference library of the London art dealer, M. Knoedler and Company. The acquisition added thousands of rare art volumes, exhibition catalogues, periodicals, and annotated auction catalogues dating from the early nineteenth century. Soon after, the Museum’s board of trustees officially named the library in Jean’s honor. Jean continued to expand the Chrysler’s library holdings until her death. Today, the Jean Outland Chrysler Library boasts more than 300,000 volumes and is widely hailed as one of the most significant and extensive holdings of its kind in the Southeast.

Walter P. Chrysler, Jr. and Jean Chrysler

In late 1981, Jean Chrysler suffered a stroke that led first to her hospitalization and then tragically to her death on January 26, 1982. She was sixty years old. Walter was devastated by her sudden passing, her family and friends stunned and grief-stricken. She was buried in the Chrysler family mausoleum in Sleepy Hollow Cemetery near Tarrytown, New York. Walter was interred alongside her six years later. Though the two were laid to rest in New York, they created a vibrant, living memorial to their passionate love of art at the top of The Hague in Norfolk. We invite you to visit the Chrysler Museum of Art and enjoy the extraordinary collections that Walter bestowed on it and that have inspired a vibrant half-century of growth. But as you marvel at the masterpieces, don’t forget that it was Jean who brought them all home.

**For a full account of Jean Outland Chrysler’s life, see particularly Peggy Earle’s excellent Legacy: Walter Chrysler Jr., and The Untold Story of Norfolk’s Chrysler Museum of Art, University of Virginia Press, Charlottesville and London, 2008; Jefferson C. Harrison et al., Collecting with Vision: Treasures from the Chrysler Museum of Art, D. Giles Limited, London, 2007; William S. Rodner, “Jean Esther Outland Chrysler (1921-1982), Dictionary of Virginia Biography, Library of Virginia, Richmond, vol. 30, 2006, pp. 238-239; and Vincent Curcio, Chrysler: The Life and Times of an Automotive Genius, Oxford University Press, Oxford and New York, 2000.