- Open today, 10 am to 5 pm.

- Parking & Directions

- Free Admission

Idelle Weber: American Pop Pioneer

Idelle Weber in front of Munchkins I, II, & III at the Friends of Museum Reopening Preview. May 8, 2014. Photo by Charlie Gunter.

After a distinguished career spanning more than half a century, New York artist Idelle Weber passed away, surrounded by family, on March 23. She was 88 years old. Though the obituaries hailed her as one of the most creative members of the post-World War II New York School, Idelle enjoyed no such recognition during her early years when she was active as a Pop artist in 1960s Manhattan. She exhibited her work in important shows alongside Andy Warhol and other key Pop players, was represented by major gallerists, and received consistently enthusiastic press. But the movement was dominated by male artists such as Roy Lichtenstein, Tom Wesselmann, and Warhol, leaving her and other talented women visual artists such as Margorie Strider and Rosalyn Drexler outside the historical pantheon until very recently. Only in the last decade has she come to be widely celebrated as an American Pop pioneer.

I first visited Idelle in her Soho studio in 2013. By then, her critical reappraisal was well underway. Her art had been featured in the groundbreaking 2010 exhibition Seductive Subversion: Women Pop Artists, 1958–1968, and her Pop masterpiece Munchkins I, II, & III had famously made the cut in Gary van Wyck’s acclaimed book Pop Art: 50 Works of Art You Should Know, published in 2013. Over the next few years, I returned to Soho with several Chrysler friends and patrons. All of us were charmed by Idelle’s warmth, wit, and insider reminiscences, and we were dazzled by the rich artistic archive her studio contained.

Chrysler Museum Members visit Idelle Weber in her Studio in 2015.

With laudable foresight, in 2013 the Chrysler acquired Idelle’s Munchkins, which has come to be recognized as the definitive expression of her stark, “Mad Men-esque” Pop style. In the painting, gray-flanneled businessmen, presented in silhouette, ride the escalators of the newly opened Pan Am (now MetLife) Building. Though the image may seem emotionally cool and detached, the painting’s title, Munchkins, suggests a more pointed appraisal of these elite Manhattan executives—implying that, like the tiny creatures in The Wizard of Oz controlled by an evil witch, they are mere cogs in an all-powerful corporate machine. An exacting technician, Idelle painted the thousands of squares in the minutely patterned, “Yellow Cab” background completely by hand. When questioned by Warhol why she didn’t speed the process by stenciling her backgrounds with specially cut rubber paint rollers, she dryly responded, “Nuance, Andy, nuance.” By then, Idelle was both a wife and mother. Her husband Julian was a partner in a prestigious Manhattan law firm, giving her a unique opportunity to observe the executive class up close. She painted the gigantic Munchkins in the family’s cramped Manhattan apartment, her two young children in tow.

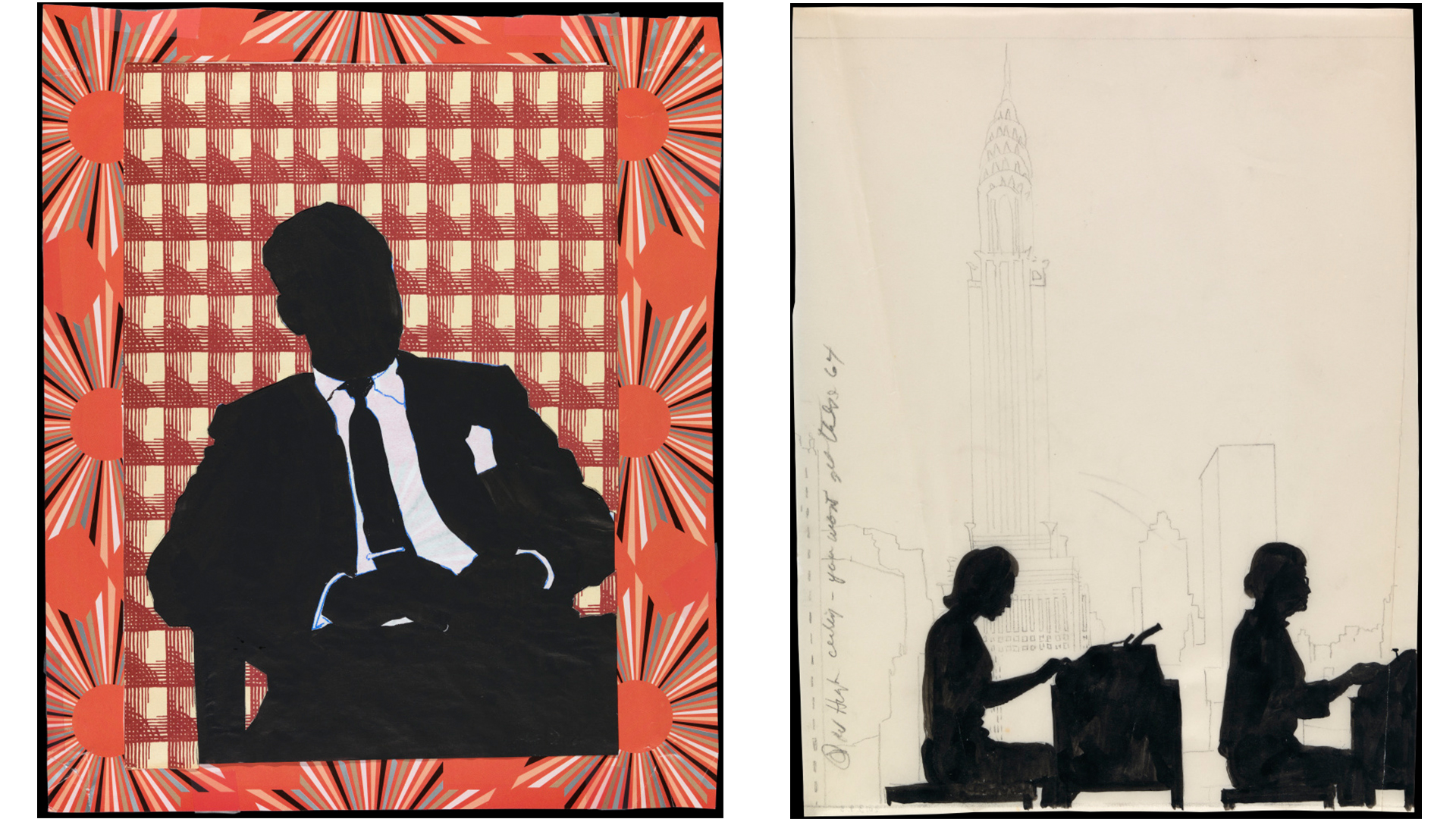

(Left) Idelle Weber (American, 1932–2020), Mr. Chrysler, 1970, Collage, Gift of Hollis Taggart Galleries, New York, 2013.9.1

(Right)Idelle Weber (American, 1932–2020), High Ceiling-You Won’t Get This, 1964, Tempera and graphite on vellum, Gift of Hollis Taggart Galleries, New York, 2013.9.3

Along with Munchkins, the Chrysler acquired two of Idelle’s smaller works, Mr. Chrysler and High Ceiling—You Won’t Get This. In Mr. Chrysler, an elegantly suited businessman lounges against a densely patterned, Art Deco-esque background. I once asked Idelle if the work was, in fact, a portrait of our own Walter P., Jr. She paused and then said, “Not really.” It was, she said, a more generalized depiction of the glamorous ’60s businessmen who occupied the corner offices in the Chrysler Building and other iconic Midtown highrises. In High Ceiling, Idelle offered a wry assessment of the inequities that plagued the professional advancement of women in the ‘60s workplace. Though the two secretaries in the artwork labor diligently at their typewriters, the title of the work makes it clear that they will likely never advance in the company. While Idelle’s male executives serenely ascend the corporate ladder/escalator, their female colleagues are destined to languish forever in the typing pool.

Idelle Weber (American, 1932–2020), Color Lesson VI, 1984, Oil on linen, Gift of Kitty and Herbert Glantz, 2015.9

Weber’s career was by no means confined to the 1960s. In fact, she continued creating and exhibiting into the 2010s, performing an almost preternatural succession of thematic and stylistic one-eighties that kept her in the vanguard of contemporary art. By the early 1970s, she had abandoned Pop altogether and emerged as a leader of the New York Photorealists. She began to paint local fruit and vegetable stands, and even the trash that had washed into the gutters near her studio, with a hard-edged precision and technical brio that astonished the critics who had only just come to know her Pop work. In the 1980s, she changed yet again as she turned to more traditional landscape themes, adding floral and garden scenes to her repertoire. She loosened her earlier realist touch to create lyrical visions of nature suffused with color and light. Her favorite sites were local—the Bronx Botanical Garden and the grounds of Old Westbury on Long Island—but she also visited and painted Claude Monet’s famous garden in Giverny.

As luck would have it, in 2015, the Chrysler was given one of the most spectacular of Idelle’s ‘80s garden paintings. Color Lesson VI depicts the Pergola and Lotus Pond at Old Westbury Gardens. With a fluent brush and a radiant palette featuring cool blue and green tones, she masterfully evokes an arc of purple irises ringing the pond and the swirl of reflections it casts on the water. Color Lesson VI serves as a vibrant contemporary update of a timeless pictorial theme that stretches back centuries: the beauty and spiritual power of flowers and gardens. One need only place Munchkins and Color Lesson VI side by side to gauge her extraordinary artistic range. Idelle was also famed for her small lucite cubes, three of which are on view in the recently reopened Museum of Modern Art.

McKinnon Modern & Contemporary Galleries, Gallery 223, Summer 2020

Idelle loved the Chrysler. She joined us at the Museum’s grand reopening in 2014 and was “thrilled with the museum” and “overwhelmingly impressed” by its collection and staff. I stayed in touch with her until 2017, when her health began to fail. Even then, she pressed on with her work, creating a final suite of paintings depicting, quite simply, fields of grass—pure, serene, eternal.

Vivian Bullaudy, Jeff Harrison, and Idelle Weber at the Friends of Museum Reopening Preview, May 8, 2014. Photo by Charlie Gunter.

Today, Idelle Weber is most celebrated for her Pop period, though it is only a matter of time before the totality of her art is fully rediscovered and she is recognized as one of the most inventive and versatile artists of our era. But at the Chrysler, we already know that.

– Jefferson Harrison, PhD, Chief Curator Emeritus