- Open today, 10 am to 5 pm.

- Parking & Directions

- Free Admission

Artful Silence: Conveying Black Experiences in Art

–DeAnne Williams, Content Manager

Between 1808 and 1865, people who were enslaved journeyed from Virginia’s tobacco fields to the cotton fields of Louisiana. During this domestic slave trade, families endured harsh conditions with little provisions. Silently, they suffered. Their goal: avoid the whip of the master and survive what became known as the Slave Trail of Tears.

The burden of silence for Black people in America did not end when slavery was abolished. In the absence of free expression, many have turned to music, literature, visual arts, and more to express their pain, anguish, and oppression. Inside a Silent Tear, a virtual conversation led by Chrysler docent Becky Livas; Dr. Amelia Ross-Hammond and Joan Rhodes-Copeland of the Virginia African American Cultural Center; and Kimberli Gant, PhD, the Chrysler’s McKinnon Curator of Modern & Contemporary Art, will explore these silent cries in the Museum’s artworks that were created by Black artists. “Art can take one inside the artist’s mind. Art is an ageless form of expression that has been used by generations to express joy, anger, fear, or ignite racial protests against inequality across various cultures, whether brought on by political unrest, ethnicity, or social unrest. For many, when there are no words to express their feelings, people gravitate to artwork that speaks to them. Its power brings healing and unity,” said Ross-Hammond.

Loretta Pettway (American, b. 1942) Untitled (Block and Strip Quilt), 2003 Cotton and polyester fabric Purchase, Gift of Friends of African American Art and Walter P. Chrysler, Jr. by Exchange, 2005.2

Loretta Pettway’s Untitled (Block and Strip Quilt), one of the works showcased in the Chrysler’s upcoming program, reflects unity and the artistic legacy of Gee’s Bend, a small insular community in rural Alabama that has developed a remarkable quilt making tradition over the past 100 years. Descendants of slaves who worked the Pettway plantation, the women of Gee’s Bend have crafted quilts that not only keep them and their families warm at night but are also striking works of art.

Livas, who hails from a family of educators who were classical music and arts enthusiasts, has always recognized the arts as powerful vehicles of expression. As a child, she took piano, violin, and cello lessons and studied ballet earlier. She also witnessed the talent of Black performers while seated in the balcony of the Center Theater, now the Harrison Opera House, and enjoyed learning about The Harlem Renaissance from her parents. “[The Harlem Renaissance] gave these artists pride in and control over how the Black experience was represented in American culture. The influence would last forever in the Black spirit of creation. My parents would discuss the people involved in the literature and music at the dinner table in the 1940s and ’50s, and the movement set the stage for the Civil Rights Movement,” she said.

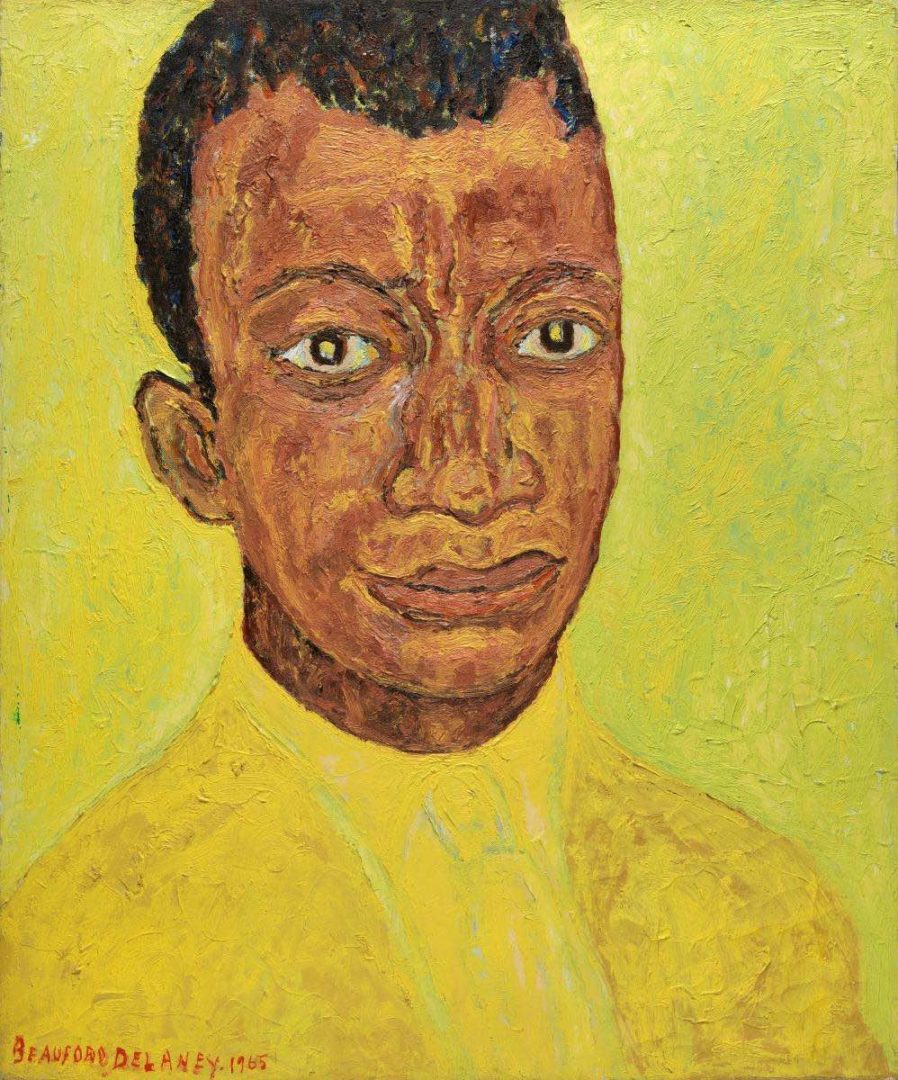

The Chrysler’s program will highlight Portrait of James Baldwin, an artwork by Harlem Renaissance artist Beauford Delaney. He met Baldwin in 1940, when the budding writer was only a teenager, and painted the portrait to celebrate their lifelong creative friendship. Delaney became a spiritual mentor to the Civil Rights activist based on their mutual struggles against homophobia, poverty, racism.

Livas can relate to their experiences of racism and, like many artists and activists, pursued her goals amid swarms of insults, dismissals, and disrespect. “You don’t belong here,” one professor told her at Cedar Crest College in Pennsylvania. Later, a classmate at the predominantly white institution questioned a picture of Livas’s parents’ home. “You can’t live in a house like that. Negroes don’t live in houses like that,” the student said.

Livas made local television history as the first African American female reporter in the 1970s, but her schedule often included covering local stories of the least importance that sometimes never aired. When Shirley Chisholm visited Old Dominion University during her presidential campaign, Livas’s request to cover the event was denied. The assignment was passed on to a white reporter instead. As the host of the local program People, Places, & Things, Livas interviewed Angela Davis and local Black people doing noteworthy things in the community. “Remember, this is not Soul Train,” her boss said.

She also discovered that every invitation to use her voice wasn’t always a good one. “I refused to do some of the work I was offered by a local (now national) company that does commercials, voice-overs, and industrial movies because they wanted me to do what I call their version of ‘black voice,’ using an accent that indicated ignorance and slow thinking along with passages of split verbs,” Livas said.

Robert Colescott (American, 1925-2009), Listening to Amos and Andy, 1982 Acrylic on canvas, Gift of the family of Joel B. Cooper, in memory of Mary and Dudley Cooper, © Estate of Robert Colescott, 2002.26.4

Robert Colescott’s 1982 work Listening to Amos and Andy uses humor to expose such stereotypes that were evident in radio for decades. The artist takes on blackface minstrelsy in the form of Amos and Andy, the long-running radio serial in which two white voice actors played Black characters. One actor’s shadow shows the exaggerated features of racist caricatures. The other actor’s white hand takes on black skin as it extends through the radio and into the living room below.

In retirement, Livas considered doing voice-overs again but decided against it. “I expected they’d changed but, nope, they had enough whites to do what I could do, and I guess enough Blacks to do what they wanted them to do,” she said.

Livas and Ross-Hammond admire artists who continue to stand up for social justice and express themselves through art. Livas says the power of art is evident in Nine Black Artists Reflect on the Question: ‘Is America at a Point of Reckoning?’, an article published last summer by The Washington Post. As the country drowned in social and racial unrest last year, pain and frustration emerged in vibrant images sprawled across makeshift outdoor canvases. Similar themes appear in works in the Chrysler collection, though they were created long before 2020. “[Art] has become a power to display blatantly the systematic injustice, racial disparity, and social inequity in the judicial system,” said Ross-Hammond. “The bright colors display anger like piercing arrows or gun shots piercing the hearts and minds of the many protesters. Art cast a light on our country’s inhumanity of man to man. Art is a powerful means of expression, and in several countries around the world, art is associated with supernatural spiritual powers. Art can be a vehicle for conveying change, healing, and comfort. Its influence has a long-lasting effect on society.”

As Ross-Hammond prepares to take a closer look at Black artists in the Chrysler collection and explore themes of silence, she is reminded of lyrics from Lift Every Voice and Sing.

“God of our weary years: God of our silent tears.

Thou who has brought us thus far along the way

Thou who have by thy might, brought us into the light.

May we forever in the path we pray.”

The Black National Anthem written by James Weldon Johnson as a poem was first performed in 1900 by a choir of 500 schoolchildren in Florida. “Historically, it was quite unacceptable for slaves to cry out loud. A careful view of these artworks conjure empathy for its subjects that touches the heart, mind, and spirit of the viewer. Beneath the surface lies a soul who has had trauma, systemic racism, and generational abuse. [Johnson’s] emotions are so full that [the song] brims over into that permissible tear to avoid showing weakness. Tears conveyed their plight as they quietly sang: ‘God of our weary years: God of our silent tears.’”

Hear more from Ross-Hammond, Livas, and other panelists and examine these themes in the Chrysler collection during Inside a Silent Tear, Thursday, February 18 at 7 p.m. The virtual conversation will be held via Zoom. Register for the virtual event here.