- Open today, 10 am to 5 pm.

- Parking & Directions

- Free Admission

A Sound Capsule from Nineteenth-Century Richmond: The Sheet Music Albums of Judith Marx Myers

–Dr. Virginia Whealton, Assistant Professor of Musicology, School of Music, Texas Tech University.

If you have seen Bridgerton, Vanity Fair, or any screen adaptation of a Jane Austen novel, you know that no early nineteenth-century English period drama is complete without a scene in which a character—often an eligible young lady—sits down at the piano and performs for company. Educated young men and women in the United States similarly were expected to be musically proficient. The children of Moses and Eliza Myers were no exception, but they were not the only accomplished amateur musicians to live in the home that is now the Moses Myers House, an historic home in Norfolk administered by the Chrysler Museum of Art. Judith Marx of Richmond, who married Myer Myers in 1826 and eventually settled in Norfolk, was an accomplished pianist and singer in her own right.

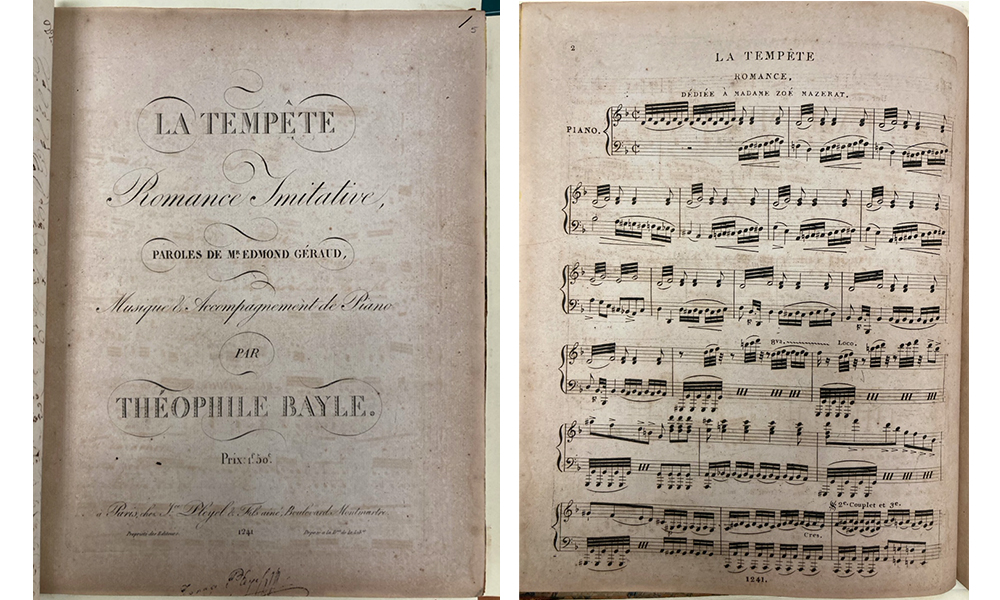

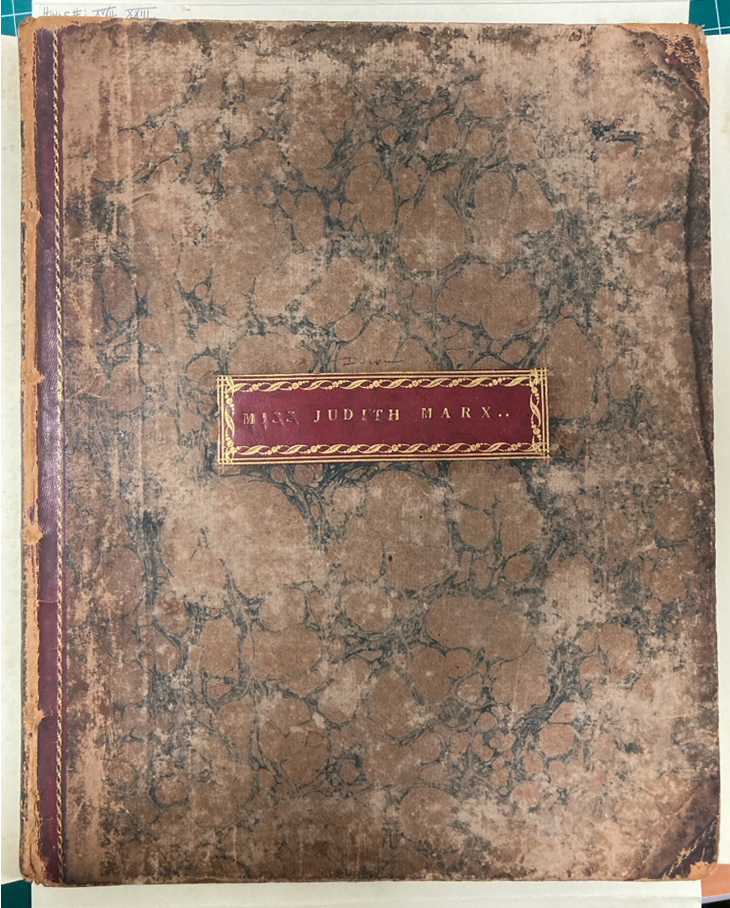

Judith left behind a collection of more than 100 pieces of sheet music. Such collections can be challenging to interpret, but they can offer many clues about their collectors. Judith’s has every indication that she was a woman of dedication and refinement. She had a variety of music for voice, for solo piano, and for harp. She had an impressive array of challenging and unusual Parisian repertoire, like Théophile Bayle’s romance “La Tempête,” shown in Figure 1. And she displayed her music in beautifully bound albums, like that shown in Figure 2.

Figure 1. Théophile Bayle, “La Tempête” (Paris: Ice. Pleyel & Fils, n.d.), MM 2007.10

Figure 2. Cover, MM 2007.10

The contents and appearance of her collection could not help but impress, but did Judith look only upon music as a way to bolster her social position, demonstrate her skill, or while away few pleasant hours? I suspect not. In addition to the four striking albums that bear Judith’s name, there are three humbler albums that contain music that belonged to her friend Mary Gabriela Whitlocke.

Mary Gabriela was one of the seventy-two victims of the Richmond Theatre Fire of December 26, 1811. This tragedy, depicted in Figure 3, profoundly touched the young state of Virginia. Judith’s father, Joseph Marx, became part of the committee to erect a public memorial to the victims, which stands in Richmond to this day.[1]

Correspondence confirms that Mary Gabriela’s family sent this music to Judith, and that this gift gave the twelve-year-old Judith comfort. After that, there is no further mention of Mary Gabriela’s music in the extant archival sources, yet the story of Mary Gabriela’s music does not end there.

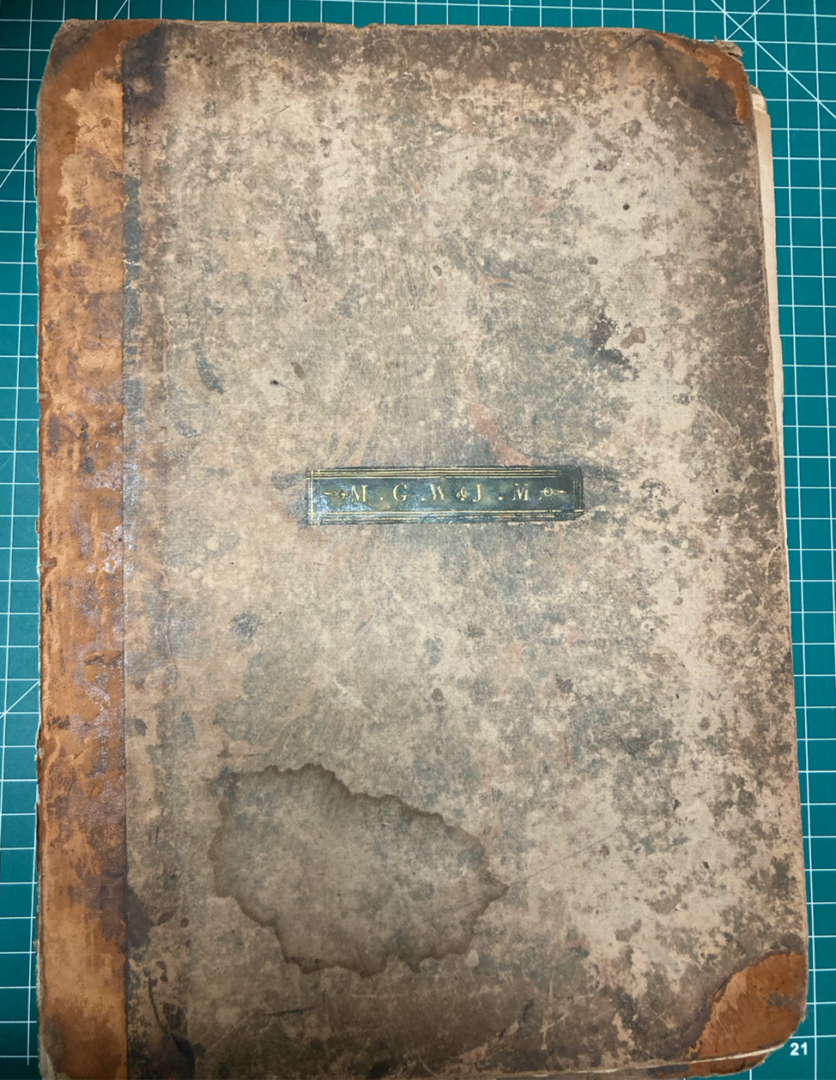

Two of the albums that bear Mary Gabriela’s name contain just her music, but one MM 2007.xx, has “M.G.W. & J. M.” on the cover, as shown in Figure 4. Bearing both Mary Gabriela’s and Judith’s initials, this album likely was bound after Mary Gabriela’s death. This was highly unusual and was a mark of the deep friendship shared by the two girls, a friendship that transcended the difference in their religious faiths; Mary Gabriela belonged to a Christian family and Judith to a Jewish one.

Figure 4. MM 2007.31

Even though Mary Gabriela’s music was much simpler than the music that Judith went on to collect in her late teens and twenties, Judith evidently still used and cherished it. Because she put her own marks in Mary Gabriela’s music and dated one of her notes “October 1821,” we know that she was using this music at least a decade after Mary Gabriela’s death. And when the Myers music collection was donated to the Chrysler Museum, Mary Gabriela’s music remained alongside Judith’s.

When I began researching the Myers music collection two years ago, four of the thirty-two bound albums, including two of Mary Gabriela Whitlocke’s, were missing. Fortunately, these albums had been microfilmed, so I could gain some idea of their contents, but I still wanted to see the original objects. I knew I likely would, with time. Such objects have a way of hiding in plain sight.

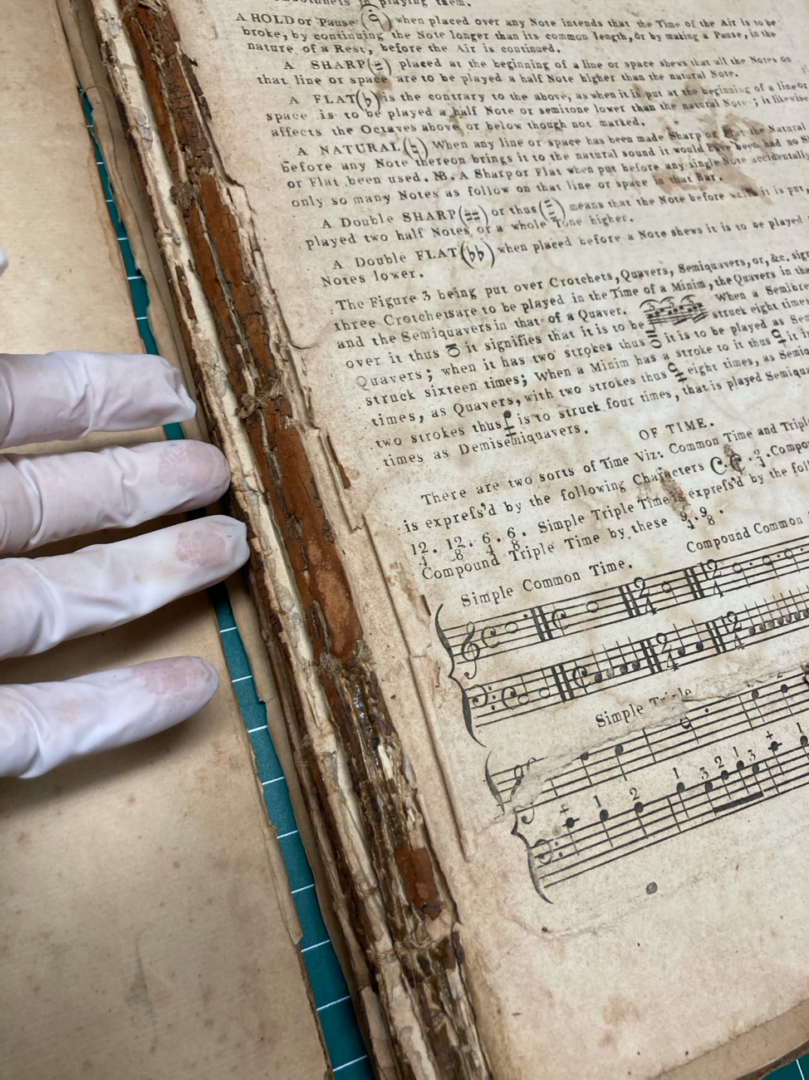

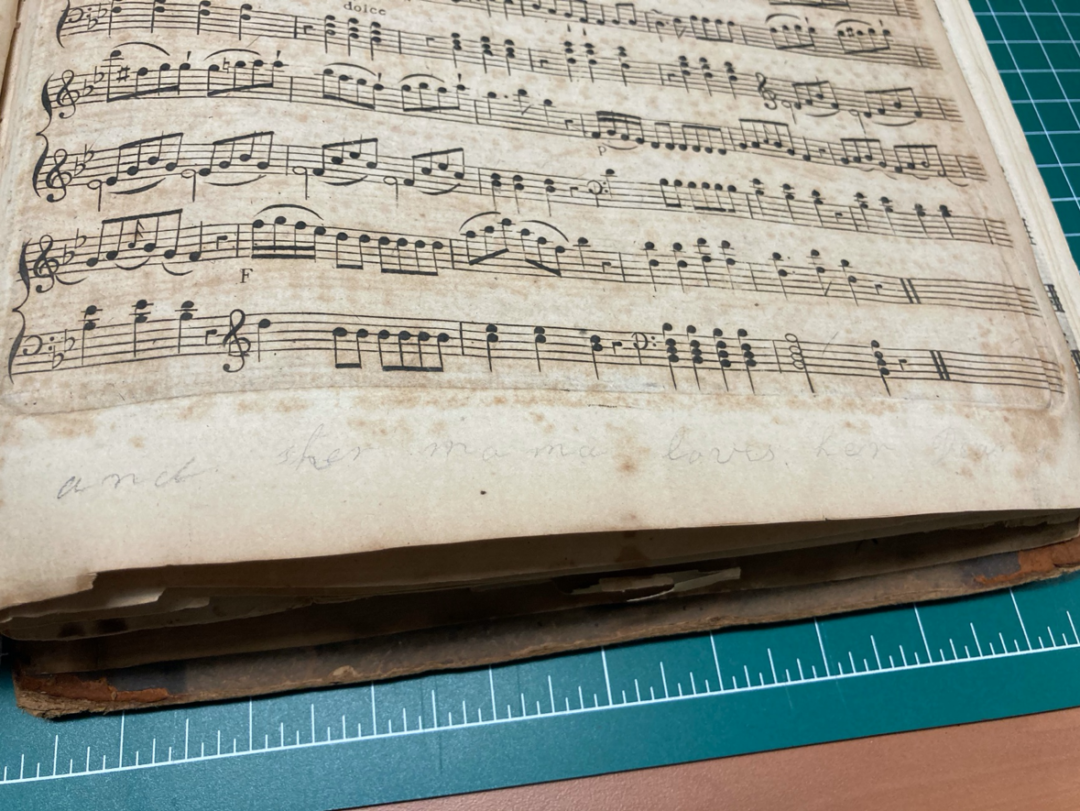

Sure enough, over the summer, while searching through some of the Myers’ business records, I found one album. Then, just last month, when rummaging under an old handwritten phone book, I found the two missing Mary Gabriela Whitlocke albums. Both of these albums are very fragile, due in part to the way that they were bound in a less sturdy way than most of the other albums in the Myers music collection. As you can see in Figure 5, the binding on one of Mary Gabriela Whitlocke’s albums has completely broken apart.

Figure 5. Binding, MM 2007.31

As I turned through the delicate pages, I feasted on many details that had not been visible on the microfilm. I saw Mary Gabriela was a scribbler, putting all sorts of notes around her music. One of them, spread across the bottom of several pages, was particularly poignant: “Mary G. Whitlocke’s Music / She loves her momma dearly / and her momma loves her dearly.” These faint pencil markings are shown in Figure 6. Mary Gabriela’s mother died five years before the fire that claimed her daughter’s life.

Figure 6. Pencil markings in MM 2007.31

Several other albums in the Myers music collection likely were donated to Judith by friends in Richmond, as they bear the names of women who lived near her. In coming months, I look forward to continuing to use Judith’s music collection to better understand her and her world.

The Moses Myers Music Collection is housed in the Jean Outland Chrysler Art Library.

[1] Meredith Henne Baker, The Richmond Theater Fire: Early America’s First Great Disaster (Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 2012), 159.