- Open today, 10 am to 5 pm.

- Parking & Directions

- Free Admission

Nudes and a Marlin

One of the gifts of this COVID time (do admit, we’ve got to find something) is perhaps our freedom to go online, tracking random thoughts down rabbit holes and digging up facts we never knew we needed. For instance, who knew a 900-pound marlin could end a friendship? And further, sports fishing nuts aside, who knew a writer and an artist would fall out over a fish?

Recently, I found out it’s possible and it actually happened. Henry Strater (1896–1987), a landscape and figurative artist, caught the marlin that Time magazine credited to his buddy Ernest Hemingway in 1936. To make matters worse, Hemingway never corrected the mistake! And apparently, Hemingway spent so much testosterone taking pot shots at sharks, who were ripping at the hooked marlin before Strater got it into the boat, that half of the marlin’s backbone was showing in the last photo of the two men together. Talk about not giving credit where credit is due.

A friendship caput over a fish—imagine that. At one time, they were happy sparring partners. In fact, Strater is said to have invited Hemingway to box in his art studio the second time they met. The first was in 1922, but I’m getting ahead of myself. Our theme is giving credit where credit is due. That’s always a good policy, and that’s what this whole search is about.

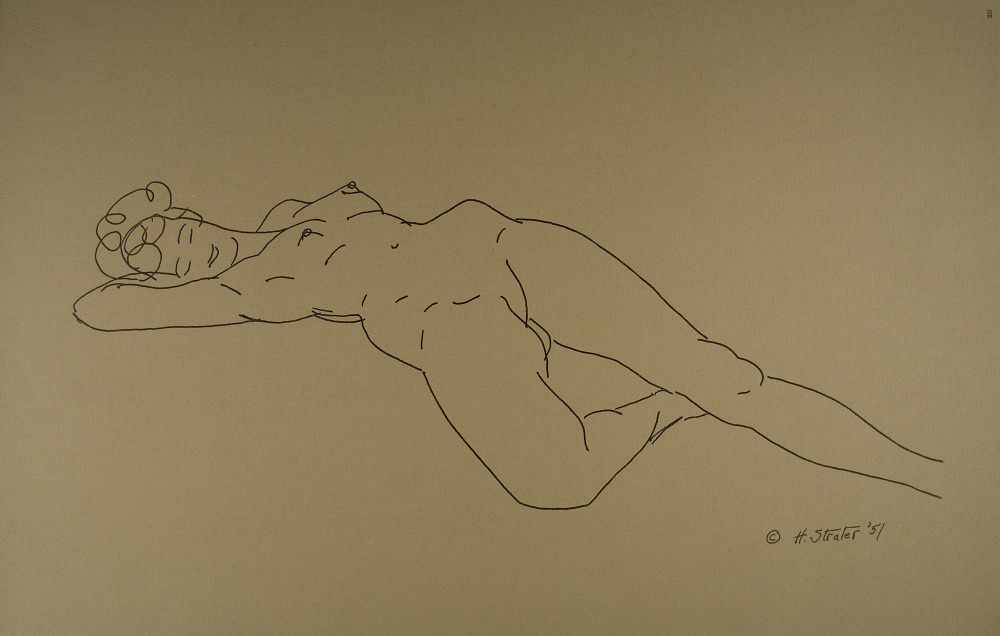

You may be wondering how Strater made his way into Chrysler Museum history. Well, you can thank the Norfolk Society of Arts (NSA) for that. The NSA has a century-old mission of promoting arts and culture in our community and providing financial support to the Chrysler Museum of Art. In the spirit of that mission, the NSA donated several lovely ink-on-paper sketches by Strater to the Chrysler Museum in the 1950s. At first glance, most of them seem somewhat racy for a proper pre-World-War ladies’ society. They’re nudes.

On second glance, and after research, I’ve gotta credit somebody prescient with collecting and donating the sketches, as they’ve proven to be of great value—at least to me from an art history perspective and also from a “Bro-mance” perspective—think Lost Generation. Strater knew all the early century guys, apparently. You know, the writers and artists who’d head on to Paris and skulk around with Gertrude Stein and the ones who’d foray into Spain, where Hemingway never saw a bullfight until a year after The Sun Also Rises was published.

It seems Strater sketched and described bullfights so well that his buddy Hemingway was able to bring them to life in words at a time when he was being criticized for being a writer only capable of describing what he actually saw. Strater was no stranger to writing. He worked with the best of them, editing the Daily Princetonian and spending time on staff at the Kansas City Sun. When asked why he chose art over a writing career, Strater noted the choice between life staring at a typewriter or fixing his gaze upon a beautiful woman. For him, the choice was obvious. “I taught Scott (yep, Fitzgerald) not to be afraid of the devil or the dark,” he said.

Strater’s preference certainly explains his nude sketches in the Chrysler collection, but his decisions lend little insight into the whole man. Born in Louisville, Kentucky to a wealthy snuff manufacturer, he protested the United States’ participation in the First World War while in college at Princeton. He got listed as a “conscientious objector” on his draft card and volunteered for the Red Cross but was injured on leave in France. He was so embarrassed to have ladies cooing over his war injury, which was really just a fall, that he signed up with the Belgians to legitimize the deal and then spent his idle time studying at l’Ecole Julien while awaiting transport home from Paris once the war ended.

His love affair with Maine—the state, not a woman—likely began in 1919 with studies at the Hamilton Easter Field School of painting in Ogunquit, where thirty years later he helped establish the Ogunquit Museum of American Art. He was concerned that post-war visual artists were being overlooked in favor of writers. While writers’ works sold in the millions, artists made one thing at a time. And since he fell out with Hemingway in 1936, it’s not unlikely this concern was amplified as the fortune and fame of writers such as his old friend grew while the fates of Lost Generation visual artists fluctuated. Remember, there was never another Armory Show of 1913, the one and only “big bang” for working artists of Strater’s era. Not even WPA initiatives saved all artists’ careers.

Strater would have known the players and had insider opinions on who deserved the fame they got. He met Hemingway back in Paris when Paris was the place disillusioned young men wanted to be. Circa 1922 at one of Ezra Pound’s afternoon teas with folks like Strater’s friend James Joyce, Strater even got a doppelganger in Fitzgerald’s character Burne Holiday in This Side of Paradise.

Henry Strater (American, 1896–1987), Ruth Breton Playing, 1958, Paper and ink, Gift of the Norfolk Society of the Arts, 63.2.1C

The list of who Strater knew goes on and on, as does the rabbit hole I found myself in, which all started with my curiosity over one of his sketches in the Chrysler collection titled Ruth Breton Playing (ca. 1932). It’s among those donated to the Chrysler by the NSA. A sweet sketch, it is as if the artist simply asked a nearby child to hold still with her violin. It turns out Ruth was a child of note, a prodigy whose talents landed her all over The New York Times during her active period in the 1920s–30s. Another coincidence: she’s from Louisville like Strater. Was she a relative or neighbor? Perhaps she was attending another tea where Strater interrupted Papa Hemingway’s rants to pick up the sketch paper and ink he just happened to have on hand. In such a moment, maybe he encouraged Ruth to have at it with that bow. There are many possibilities. I haven’t followed that thread any further.

Henry Strater (1896–1987), Collection of the Ogunquin Museum of American Art

The Chrysler doesn’t own any of Strater’s painted works, but they are worth mentioning here. They are from a time before he and Hemingway dickered over the marlin. Strater spent years out west determined not to work with scores of other artists gathering in colonies in Santa Fe, Taos, you name it. Instead, he was determined to paint the great expanse of land and sky in a new way. According to him, and a few other contemporary critics, he did just that.

Invent another way to paint the west. (Sound like Hemingway?) Strater’s new approach had to do with his use of buildings or animals in the foreground to set the focal moment. The mid-spaces were “violet-grayed” out as things would be in a vanishing perspective in which we look past what’s in front of us to see the horizon, willingly glossing over what’s in the middle.

Perhaps, Strater is a kind of middle artist in the shadow of better-known men.

Color was important in Strater’s new approach. He and Hemingway philosophized over it. Color for Strater was both form and shock value. “Shock” in that color wordlessly presented what he wanted the landscape to convey. Hemingway took that note and equated it with his “iceberg theory” that the deeper meaning of something shouldn’t be stated obviously but should show through something else. Hemingway usually used a moment of violence for this or took unnecessary pot shots at a buddy’s marlin to get the sharks to leave it alone—all the while knowing darn well he’d take full credit for the catch because that’s who he was. But that wasn’t Strater. In fact, he apparently mourned his deceased friend once Hemingway died, but finally had to set all the journalists straight when they’d asked too many questions about their friendship. Strater said he was “Hemingway’d out.” Nothing iceberg about that. Just plain truth in the moment.

Strater’s moments, the memory of who he was, are healthily maintained at the Ogunquin Museum of American Art, where there’s always an exhibition of his works on view. And hopefully now he’s been made a little clearer through the Chrysler’s collection of lovely sketches. Thank goodness the Norfolk Society of Arts ladies didn’t blush too long at nudes.

–Alva Moore, Chrysler Museum Docent