- Open today, 10 am to 5 pm.

- Parking & Directions

- Free Admission

The History of Art in Colors

A CHROMATIC TOUR OF THE CHRYSLER:

BROWN PIGMENTS

Between desecration and destruction: the curious history of brown pigments in European Easel Painting

In our modern world of effervescent colors, brown seems to have lost its place in image-making. Brown might even seem to have a rather dull history as most of the hues are simple earth colors. The iron oxide rich minerals that produce these colors have always been abundantly common across the globe, with sources like clay readily available at the surface of the ground. They are certainly the oldest pigments ever employed, as seen in this Egyptian coffin created more than 2,000 years ago with red ochre, a more colorful variation of earth pigment.

Anthropoid Coffin, Roman Period (30 B.C.E.–395 C.E), Polychrome and gesso on wood, Gift of Jack Chrysler in Memory of Walter P. Chrysler, Jr., 93.32.1

Clear as Mud: A Transparent Choice of Browns

It might be hard to look at these colors with much reverence today, but historically, artists placed a great deal of focus on the quality of brown—just as much as they did any other color. As illustrated in the 1917 fictional story A Tube of Mummy, an artist laments, “I want a golden-brown for that highlight, the like of which I’ve never seen. But it must exist—somewhere on earth it must exist.”[1] In addition to searching for unique colors, painters also valued transparent color. Oil painting reigned as the most important form of art for hundreds of years in the Western world. The technique of painting relies heavily upon using the transparency of both the oil medium and pigment to create the illusion of depth on a two-dimensional surface. Natural brown earth pigments are typically opaque or semi-opaque and not ideal for glazing. Faced with limited options in pursuit of permanent, rich, transparent browns, artists had to make a choice: risk the destruction of their work by employing the readily available but often-ruinous pigment asphaltum or desecrate the ancient mummified ancestors of Egypt in search of the ultimate brown pigment.

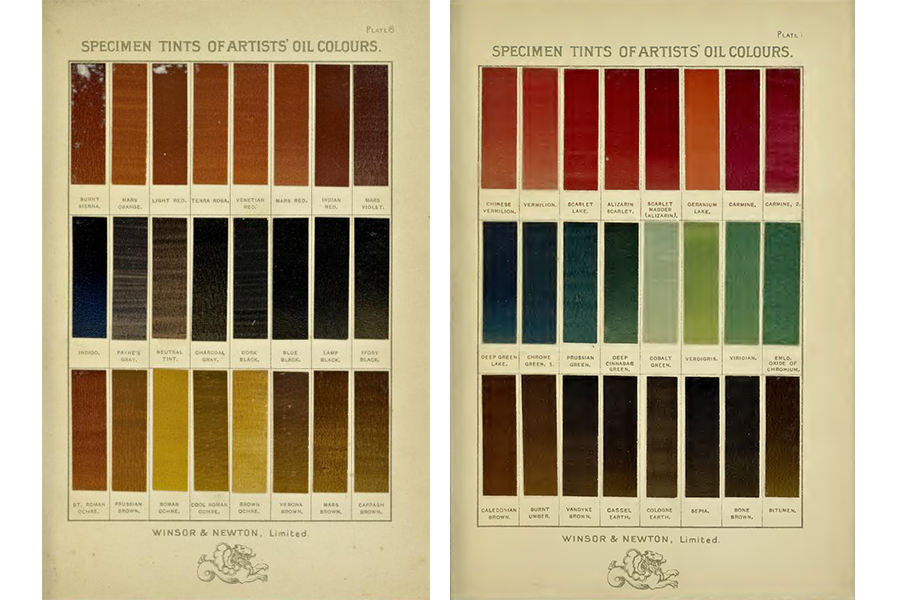

Page from Specimen tints of Winsor & Newton’s Artists’ Oil and Water Colours. 191-?. Showing ‘Cappagh’ (Mummy) Brown paint and Bitumen in Oil Paint (both in bottom right corner). Image via Archive.org courtesy of the Getty Research Institute

Problematic Paints

Asphaltum is a pigment made of mineral-rich crude petroleum that naturally seeps from the earth. Historically, the term was indistinguishable from ‘bitumen.’[2] The pigment has been used since ancient times and is said to have been favored by the Flemish masters[3] and certainly by the nineteenth- and early-twentieth-century Academic painters. It gave a rich, transparent, brown color that could not be achieved with earth, black, and other mixtures of pigments. Unfortunately, these waxy petroleum products were problematic in oil paint. Since the nineteenth century, substantial warnings have been published about the use of this pigment, detailing the ruinous cracking and flaking that can occur with its use.[4] Extreme examples are visible in the likes of William Hilton the Younger’s Editha and the Monks Searching for the Body of Harold, which was exhibited in 1834 and is held in the collection of the Tate.

William Hilton the Younger (1786–1839), Editha and the Monks Searching for the Body of Harold, exhibited in 1834, Oil on canvas, Collection of the Tate, Image courtesy of the Tate

Contemporary reconstructions of nineteenth-century recipes suggest that these pigments, in fact, will form a stable paint layer; however, the body of evidence suggests that they were either very difficult to employ or were misused to ruinous effect. Asphaltum and bitumen pigments, do in fact, have a noticeable effect on the properties of oil paint. The pigments contain antioxidants that prevent the natural chemical reactions of drying oil, and the resulting paint dries very slowly. [5],[6] Because the material dried too slowly for the normal workflow of most painters, artists attempted to circumvent this languor by adding chemical drying accelerators and quick-drying resins in place of slow oils. The modified paint quickly formed a dried top skin of paint that allowed the artist to continue painting further layers at a more typical pace, but it could ultimately lead to the wide cracks and adhesion issues often noted as the underlayers of paint cured. The effect is similar to the two-layer crackle paint system used in crafting. The result was likely exacerbated in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries when artists heavily employed resin and drier mediums. As they searched for means to create rich, thick glazes, oil paint was heavily modified with mediums like Megilps that gave gel-like texture to otherwise thin layers of transparent asphaltum and bitumen glaze. In nineteenth-century works like Miggles, we can see the likely results of this mixture of modified asphaltic paint. The wide drying cracks across the dark background pull apart the red headscarf that was painted over top, leaving fragments of red floating around Miggles’s head. These cracks likely occurred early in the life of the painting and have been inpainted with more brown color since.

George de Forest Brush (American, 1855–1941), Miggles, 1880, Oil on canvas, Gift of Walter P. Chrysler, Jr, 71.625

Miggles (detail). These images were captured before conservation work undertaken in 2020. The detail shows cracks possibly caused by asphaltic paint modified with medium and drier.

The Search for Stability: Mummy Brown

With brown’s problematic history, it’s not surprising that artists turned away from bitumen for the ultimate brown pigment. Treatises suggested the use of a much stranger pigment:[7] mummy brown. The ground body of a mummy was used from the twelfth–twentieth centuries as a pigment in Europe.[8] Nineteenth-century treatises suggest that fleshy, muscle tissue should be used for the highest quality pigment,[9] while other sources indicate the whole body should be ground. Sometimes, the body was soaked in water for several days to rinse impurities away. [10] Artists believed the paint had a delightful warm tone and wonderful transparency,[11] and, like bitumen, served as an excellent glazing pigment.[12] Angelica Kauffman is said to have painted with it.[13] Could our own Telemachus Returning to Penelope contain the remains of ancient Egyptians, even older than the Greco-Roman myth it depicts?

Angelica Kauffman (Swiss, 1741–1807), Telemachus Returning to Penelope, ca. 1770–1780, Oil on canvas, Gift of Walter P. Chrysler, Jr., 71.665

The origins of mummy brown will likely astound the modern viewer. How could anyone possibly think of processing the ancient embalmed human body for a pigment? Its origins certainly lie in the apothecary. Before colourmen served artists, the apothecary was the source of artists’ pigments. For centuries, mummies were commonly used as medicine in the Western world both in ground form and other gruesomely curious edibles like human mummy confection. Artists were drawn to this mummy medicine for its rich brown-black color and the source of this color, ancient bituminous resins used in the mummification process.[14]

As described before, bitumen as a pigment had gathered a poor reputation for instability by the nineteenth century. Mummy brown, however, had gathered more praise as an alternative. As explained in a 1926 color catalog recipe, “the [b]itumen [is] of very pure quality [being] kept dry for over 3,000 years.”[15] It was thought that 3,000 years of natural aging allowed the bitumen to reach a very stable point, resulting in paint that was less likely to crack and darken[16] [17] The perceived connections between permanency, immortality, and mummification are hard to miss in A Tube of Mummy, when the artist declares, “For years the contents of this little tin phial have been waiting the chance to do us a favor. Think of it! A Pharaoh may have and died to this great end alone, that after countless ages he might throw a dash of golden light upon your portrait, might help a canvas to immortalize the marvelous tint of your sunny hair!” [18] Indeed, nineteenth-century academic painters like Eugène Delacroix[19] and Edward Burne-Jones have been recorded to use this paint, with suggestions that traditional painters favored its stability for their fine works.[20] Could Jean-Léon Gérôme’s Orientalist depictions of Egypt also contain a small fragment of Egypt itself?

Eugène Delacroix (French, 1798–1863), Arab Horseman Giving a Signal, 1851, Oil on canvas, Gift of Walter P. Chrysler, Jr. 83.588

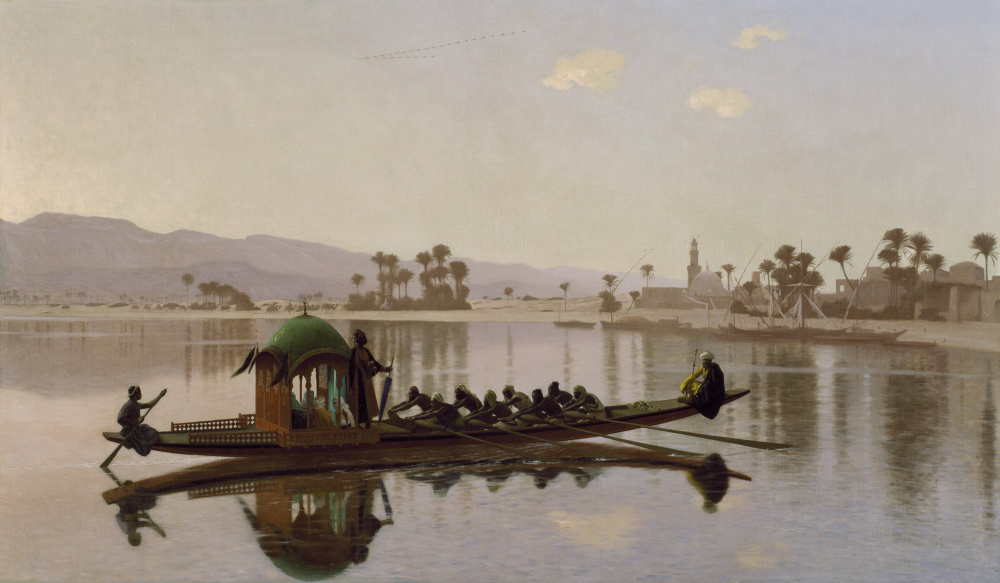

Jean-Léon Gérôme (French, 1824–1904), Excursion of the Harem,1869, Oil on canvas, Gift of Walter P. Chrysler, 71.511

Mummy brown: fact or fiction?

Despite wide documentation of its use, mummy brown is difficult to identify when used in an artwork. It’s even hard to characterize its composition when historical pigment samples are available to study. Ancient Egyptian mummification practices changed over time and varied by factors like class. Bodies could be prepared with a variable mixture of resinous adhesives, proteinaceous materials, plant gums, animal fats, and possibly other additives like beeswax and asphaltum/bitumen.[21] Furthermore, colourmen would likely modify pigments and paints to create a pleasing product with the addition of nearly any of these materials.[22]

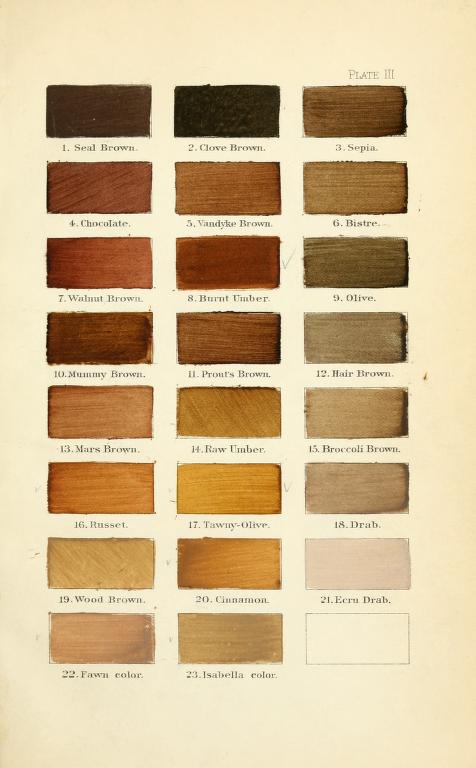

As early as the sixteenth century, the origin of these mummies was dubious. Modern Egyptians created forgeries from the recently deceased to sell to Europeans as medical mummies ran in short supply. By the eighteenth century, the use of mummies in Western medicine was discontinued as quackery, but a continued fascination with the importation of Egyptian antiquities spurred a ban on the shipment of mummies in the nineteenth century. With authentic mummies in short supply, paint manufactures of the nineteenth century largely switched to alternative colors.[23] An 1886 color guide lists Mummy Brown as a more mundane mixture of raw umber and burnt sienna with optional sepia.[24]

Page from A nomenclature of colors for naturalists: and compendium of useful knowledge for ornithologists. By Ridgway, Robert, 1886. Image via Archive.org courtesy of the Boston Public Library.

The End of Mummy and Bitumen

Despite its popularity in the nineteenth century as a more stable paint than bitumen and asphaltum, accounts of its use from the early twentieth century suggest that mummy brown was prone to producing paint layers that turned hazy, crackled, and even flaked off the canvas,[25] possibly because the pigment was largely made of the same bituminous components or adulterated with them by colourmen. These pigments all eventually fell from use, likely due to their drying issues, changing tastes in favor of more colorful paints, and the invention of modern pigments and dyes that could readily replace these colors without the need for desecration or the risk of self-destructing paint films.

Join us next week as we dive into the story of white. Despite their ubiquitous and banal nature on any color palette, white pigments give insight into a topic perhaps rarely addressed by those making or studying art: the technology that underpins and allows for the creation of paint.

-Brandon Finney, NEH Conservation Fellow

[1] Edward S van Zile, “A Tube of Mummy,” The Art World 2, no. 4 (April 6, 1917): 349–52, https://doi.org/10.2307/25588001.

[2] Raymond White, “Brown and Black Organic Glazes, Pigments and Paints,” National Gallery Technical Bulletin 10 (April 6, 1986): 58–71, http://www.jstor.org/stable/42616039.

[3] White.

[4] Erma Hermens and Joyce Townsend, “Pigments in Western Easel Painting,” in Conservation of Easel Paintings, ed. Joyce Hill Stoner and Rebecca Rushfield, 2012, 189–213, https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9781107415324.004.

[5] Georgiana Maria Languri, “Molecular Studies of Asphalt, Mummy and Kassel Earth Pigments : Their Characterisation, Identification and Effect on the Drying of Traditional Oil Paint ,” MOLART ; 9 (S.l: s.n.], 2004).

[6] White, “Brown and Black Organic Glazes, Pigments and Paints.”

[7] Sally Woodcock, “Body Colour: The Misuse of Mummy,” The Conservator 20, no. 1 (January 1, 1996): 87–94, https://doi.org/10.1080/01410096.1996.9995106.

[8] Georgiana M Languri and Jaap J Boon, “Between Myth and Reality: Mummy Pigment from the Hafkenscheid Collection,” Studies in Conservation 50, no. 3 (2005): 161–78, https://doi.org/10.1179/sic.2005.50.3.161.

[9] White, “Brown and Black Organic Glazes, Pigments and Paints.”

[10] Woodcock, “Body Colour: The Misuse of Mummy.”

[11] Woodcock.

[12] White, “Brown and Black Organic Glazes, Pigments and Paints.”

[13] Woodcock, “Body Colour: The Misuse of Mummy.”

[14] White, “Brown and Black Organic Glazes, Pigments and Paints.”

[15] Roberson Archive HKI MS. 869-1993, p xvi. Cited from Woodcock.

[16] Woodcock, “Body Colour: The Misuse of Mummy.”

[17] White, “Brown and Black Organic Glazes, Pigments and Paints.”

[18] van Zile, “A Tube of Mummy.”

[19] Philip Gilbert Hamerton, ‘The Graphic Arts; a Treatise on the Varieties of Drawing, Painting, and Engraving, in Comparison with Each Other and with Nature’ (Boston: Little, Brown, and company, 1902), pp. 318.

[20] Woodcock, “Body Colour: The Misuse of Mummy.”

[21] White, “Brown and Black Organic Glazes, Pigments and Paints.”

[22] Languri and Boon, “Between Myth and Reality: Mummy Pigment from the Hafkenscheid Collection.”

[23] Woodcock, “Body Colour: The Misuse of Mummy.”

[24] Robert Ridgway, A Nomenclature of Colors for Naturalists, and Compendium of Useful Knowledge for Ornithologists, Nineteenth Century Collections Online (NCCO): Science, Technology, and Medicine: 1780-1925 (Boston: Little, Brown, and Co., 1886).

[25] Woodcock, “Body Colour: The Misuse of Mummy.”

Bibliography

Hamerton, Philip Gilbert. “The Graphic Arts; a Treatise on the Varieties of Drawing, Painting, and Engraving, in Comparison with Each Other and with Nature.” Boston: Little, Brown, and company, 1902. file://catalog.hathitrust.org/Record/009792427.

Hermens, Erma, and Joyce Townsend. “Pigments in Western Easel Painting.” In Conservation of Easel Paintings, edited by Joyce Hill Stoner and Rebecca Rushfield, 189–213, 2012. https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9781107415324.004.

Languri, Georgiana M, and Jaap J Boon. “Between Myth and Reality: Mummy Pigment from the Hafkenscheid Collection.” Studies in Conservation 50, no. 3 (2005): 161–78. https://doi.org/10.1179/sic.2005.50.3.161.

Languri, Georgiana Maria. “Molecular Studies of Asphalt, Mummy and Kassel Earth Pigments : Their Characterisation, Identification and Effect on the Drying of Traditional Oil Paint .” MOLART ; 9. S.l: s.n.], 2004.

Ridgway, Robert. A Nomenclature of Colors for Naturalists, and Compendium of Useful Knowledge for Ornithologists. Nineteenth Century Collections Online (NCCO): Science, Technology, and Medicine: 1780-1925. Boston: Little, Brown, and Co., 1886.

White, Raymond. “Brown and Black Organic Glazes, Pigments and Paints.” National Gallery Technical Bulletin 10 (April 6, 1986): 58–71. http://www.jstor.org/stable/42616039.

Woodcock, Sally. “Body Colour: The Misuse of Mummy.” The Conservator 20, no. 1 (January 1, 1996): 87–94. https://doi.org/10.1080/01410096.1996.9995106.

Zile, Edward S van. “A Tube of Mummy.” The Art World 2, no. 4 (April 6, 1917): 349–52. https://doi.org/10.2307/25588001.