- Open today, 10 am to 5 pm.

- Parking & Directions

- Free Admission

#5WomenArtists

It started with a seemingly simple question: Can you name five women artists?

Since 2016, the National Museum of Women in the Arts (NMWA) has been asking this question on social media each March during Women’s History Month using the hashtag #5WomenArtists. The campaign raises awareness about gender inequity in the art world and beyond. Thousands of individuals and more than 1,500 cultural institutions from seven continents and 54 countries have taken part!

The Chrysler Museum has been a proud supporter of NMWA’s initiative for the past several years. Take a look at the women from our collection that we’ve highlighted in 2020.

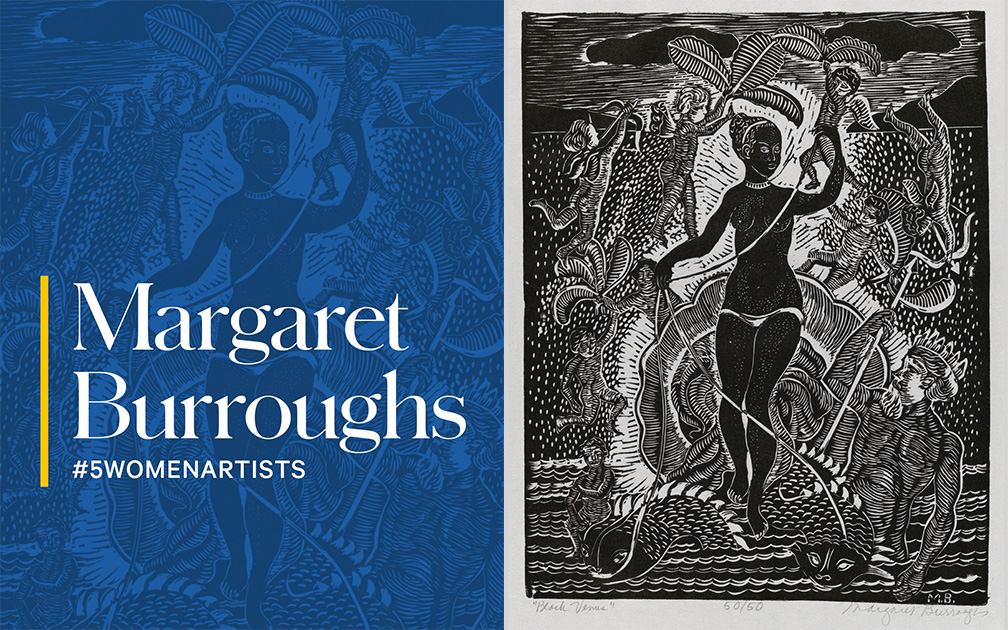

Margaret Burroughs (1915–2010) was the founder of the DuSable Museum of African American History in Chicago, one of the first museums dedicated to black history, culture, and art in the U.S. She also helped establish the South Side Community Art Center in Chicago, the only continuously open African American art center funded by the Works Progress Administration’s Federal Art Project (WPA).

Burroughs was a remarkable printmaker, sculptor, painter, poet, and public school educator. Her beautiful lithograph Black Venus (1957), illustrates the mythical birth of the Roman goddess Venus from the ocean. However, Burroughs portrays the figure as having darker skin than traditionally shown. The Black Venus is in the Chrysler’s collection and featured in Edvard Munch and the Cycle of Life, on view at the Chrysler through May 17.

Margaret Burroughs was truly a Renaissance woman, ensuring that current and future generations know their value through the Arts.

Image: Margaret Burroughs (American, 1915–2010), Black Venus, 1957, Linoleum cut on imitation Japan paper, Museum purchase, © Estate of Margaret Burroughs, 2018.17

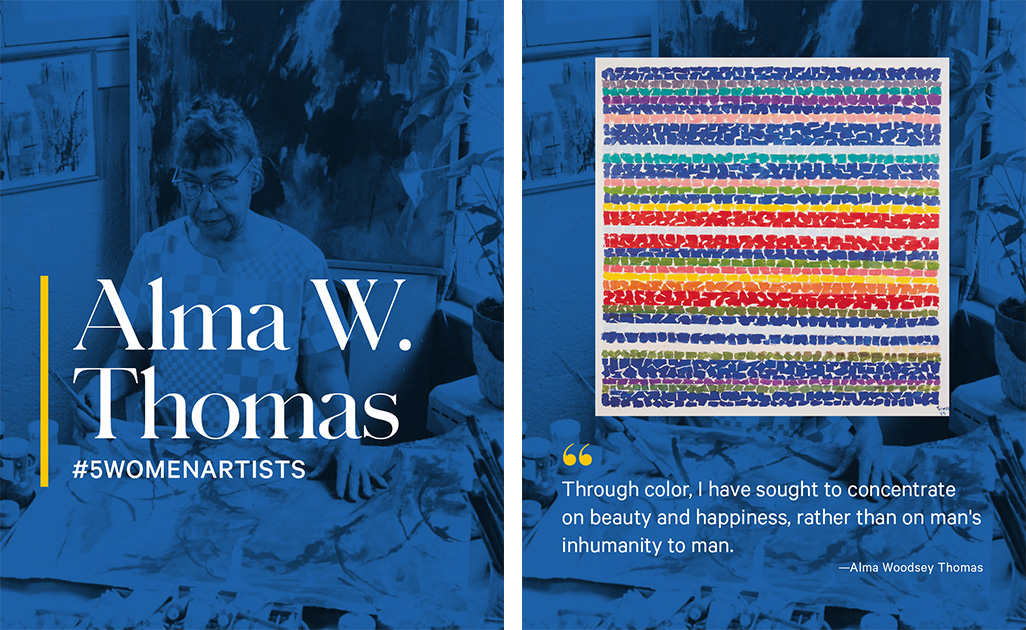

Expressionist painter Alma Thomas (1891–1978) was the first fine arts graduate from Howard University and the only African-American female artist associated with the Washington Color School. After retiring from a 35-year career as a high school art teacher at the age of 69, she became a full-time artist. At the age of 81, she became the first African-American woman to have a solo show at the Whitney Museum of American Art.

See her joyful works at the Chrysler Museum in Alma W. Thomas: Everything Is Beautiful, opening July 2021. The exhibition will give a comprehensive overview of the artist’s long life with approximately 100 works, including her rarely seen theatrical designs and beloved abstract paintings.

Left image: Ida Jervis, Alma Thomas working in her studio, ca. 1968. Alma Thomas papers, circa 1894-2001. Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution

Right image: Alma W. Thomas (American, 1891–1978), Air View of a Spring Nursery, 1966, acrylic on canvas, The Columbus Museum, Georgia, purchase and gift of the National Association of Negro Business Women, and the Artist, G.1979.53

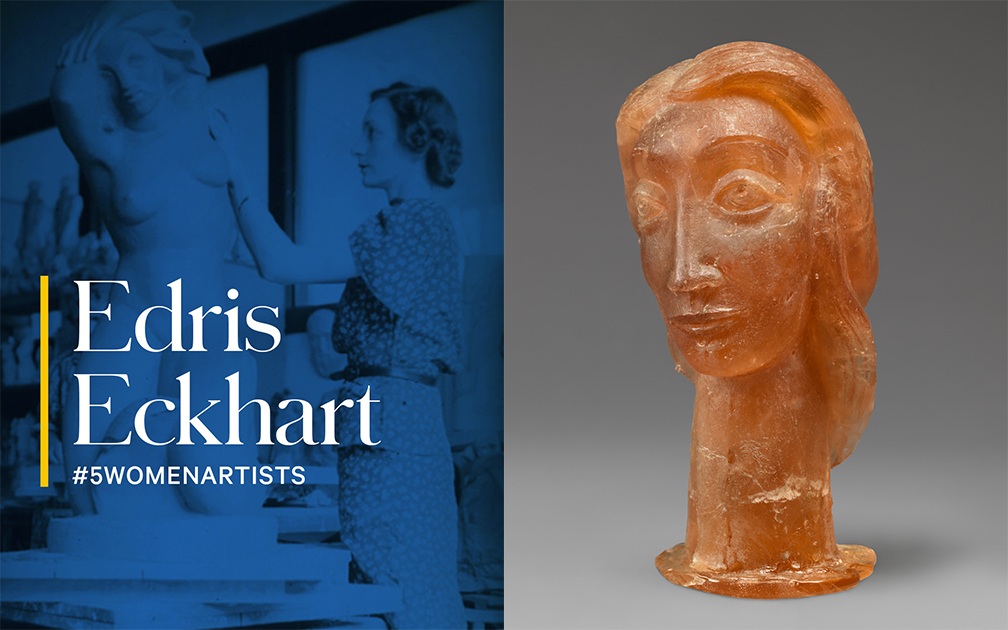

Edris Eckhart (1905–1998) was a female pioneer in the field of glass. She experimented with glass as an expressive medium a decade before the American Studio Glass Movement of 1962, which brought glass out of the traditional factory setting and into the private studio.

Born Edythe Aline Eckhardt, the artist changed her name to Edris to avoid gender stereotyping in her artistic career. Eckhart first began to experiment with glass in 1952 when she was almost 50 years old. In the 1960s and 1970s, she used techniques that few others did, including pâte de verre and lost-wax casting. Summer Day (1967) is a rare self-portrait made of cast amber glass with a rough surface texture that creates an abstract yet serene rendering of the artist.

Left image: Courtesy of Joe Kisvardai

Right image: Edris Eckhardt (American, 1905–1998), Summer Day (Self-Portrait), 1967, Cire perdue glass, Museum purchase with funds provided by Paramount Industrial Companies, Inc. and Arthur and Renée Diamonstein, 94.6

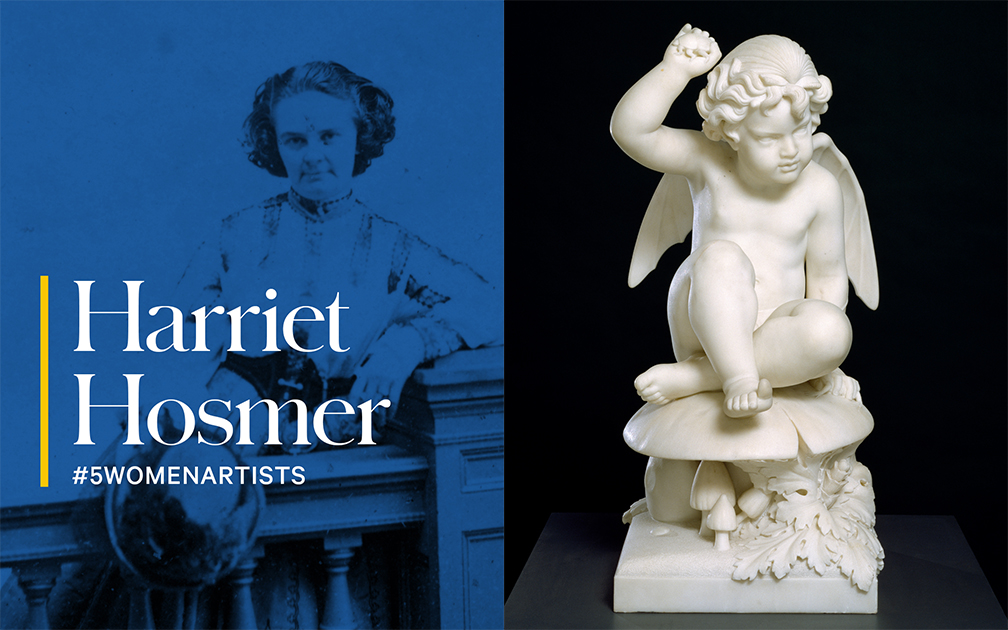

Harriet Hosmer challenged the 19th-century idea that sculpture was a profession only for men and became one of the most successful American sculptors of her time.

In a period where anatomy classrooms weren’t open to women, she took private anatomy lessons to better understand the human figure. Hosmer continued her studies in Rome, where she could experience classical statuary and practice life drawing, an unusual opportunity for female artists.

In Rome, Hosmer joined a vibrant community of American writers and women sculptors. The Chrysler holds works by several of the artistic members of the group, including pieces from Harriet Hosmer, Emma Stebbins, and Margaret Foley.

Hosmer’s Puck, depicting the mischievous fairy from Shakespeare’s A Midsummer Night’s Dream, was her most popular and lucrative subject. She repeated the composition numerous times, and along with other creations, she was able to support herself from the sale of her works — a remarkable achievement for women in her time.

Left image: James Wallace Black (American, 1825–1896), Harriet Goodhue Hosmer, 9 Oct 1830–21 Feb 1908, Albumen silver print, National Portrait Gallery, Smithsonian Institution

Right image: Harriet Goodhue Hosmer (American, 1830–1908), Puck, ca. 1855–56, Marble, Gift of James H. Ricau and Museum purchase, 86.471

Who will be #5?

Don’t let your answer be ummmmm…..

Thanks to our colleagues at the National Museum of Women in the Arts for spearheading this annual campaign.